What does the choice of furniture have to do with architecture? In recent years, I have proposed a loft renovation project for my second-year architecture studio students, with an emphasis on interior design principles that extend to the selection of furniture and the detailing of cabinetwork.

Despite the topic’s apparent simplicity—integrating architecture design with interior design—I have not often encountered a loft renovation as a studio prompt. Perhaps, because such a proposal either exacerbates deeply rooted preconceptions towards the discipline of interior design, or simply because the project’s subject matter is dismissed as not robust enough to generate learning outcomes.

Question of renovation

I will admit that the latter offers valid reasons to choose a different prompt as the renovation lacks a complex program or a difficult site condition, it doesn’t call for an innovative structural principle or prerequisites on building assemblies. Despite this, I find that my second-year students enjoy issues of renovation, perhaps for the simple fact that it offers a moment to reflect on domesticity and how we live today in a highly designed environment ranging from concept to the choice of a doorknob.

The renovation project is also an opportunity to engage students early on in issues of preservation, including topics of restoration, rehabilitation, and adaptive reuse that are deeply anchored in the professional portfolios of many architecture firms. To preserve the existing in an informed way is to partake in a sustainable architecture, offering solutions to return to an ecosystem where architects can have a strong say.

Google images: Adolf Loos -American Bar (1908), Hans Hollein -Austrian Travel Agency (1976), Steven Holl -Pace Collection (1985), Morphosis -72nd Market Street (1984), and Frank O. Gehry -Rebecca’s Restaurant (1986)

Google images: Adolf Loos -American Bar (1908), Hans Hollein -Austrian Travel Agency (1976), Steven Holl -Pace Collection (1985), Morphosis -72nd Market Street (1984), and Frank O. Gehry -Rebecca’s Restaurant (1986)

Finally, the loft renovation is not dissimilar to many projects that masters and starchitects had as the launch to their careers, namely designing modest interiors. From Adolf Loos to Frank Gehry, these projects were a way to experiment at a smaller scale—where space is often at a premium—in preparation for their upcoming big and memorable gestures; in retrospect, a moment we have all witnessed when visiting the early works of now famous architects.

The loft project

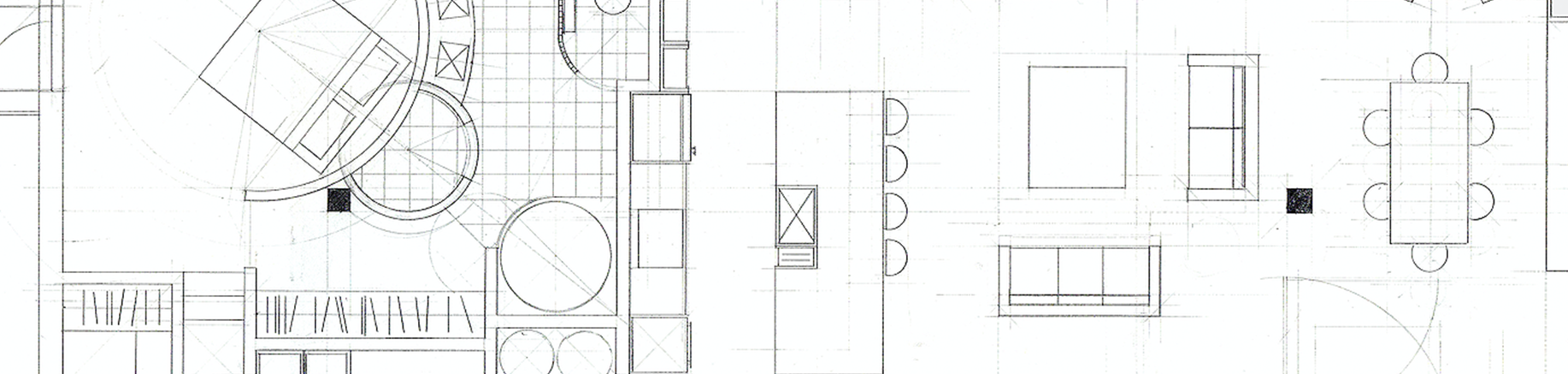

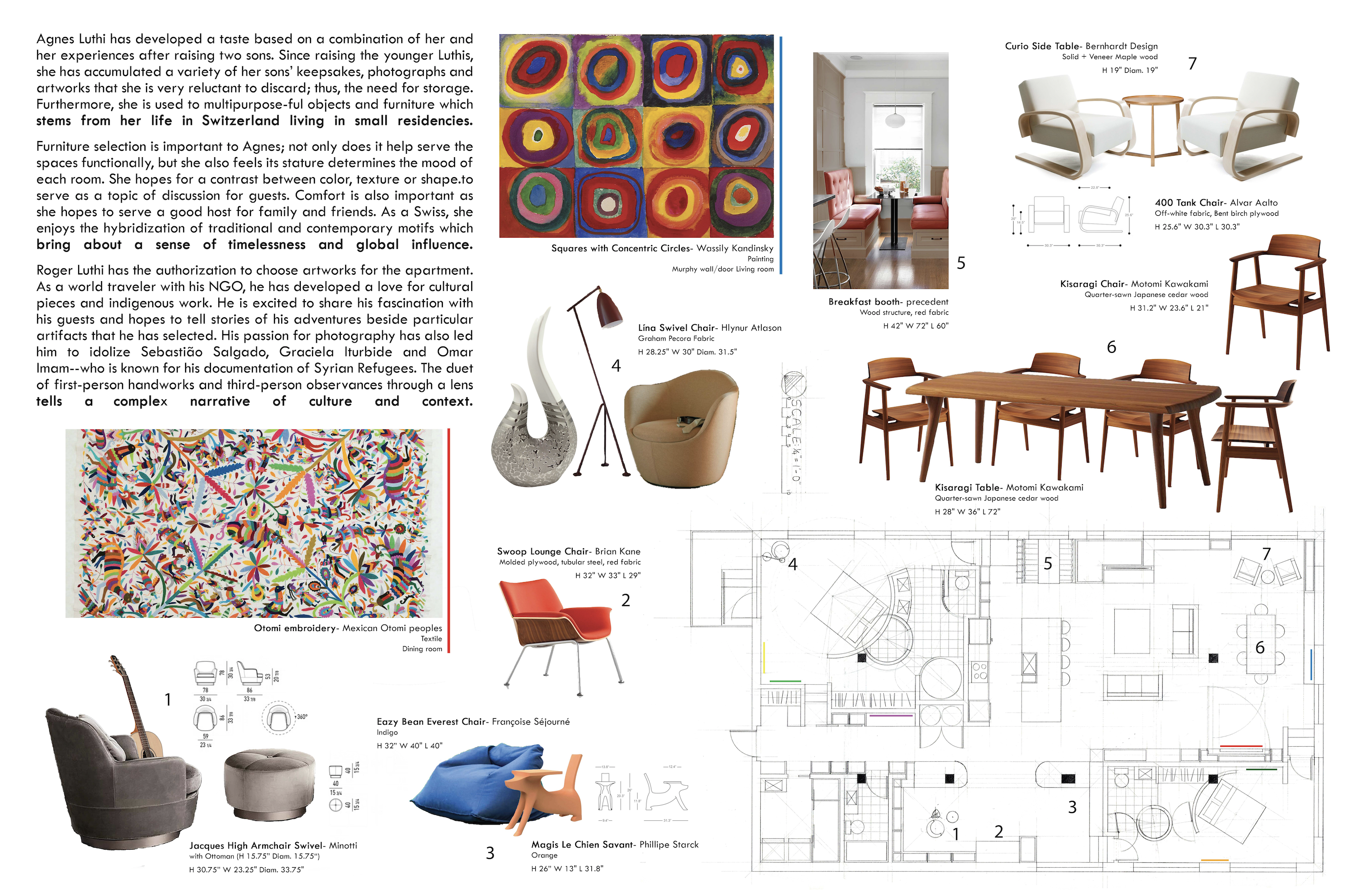

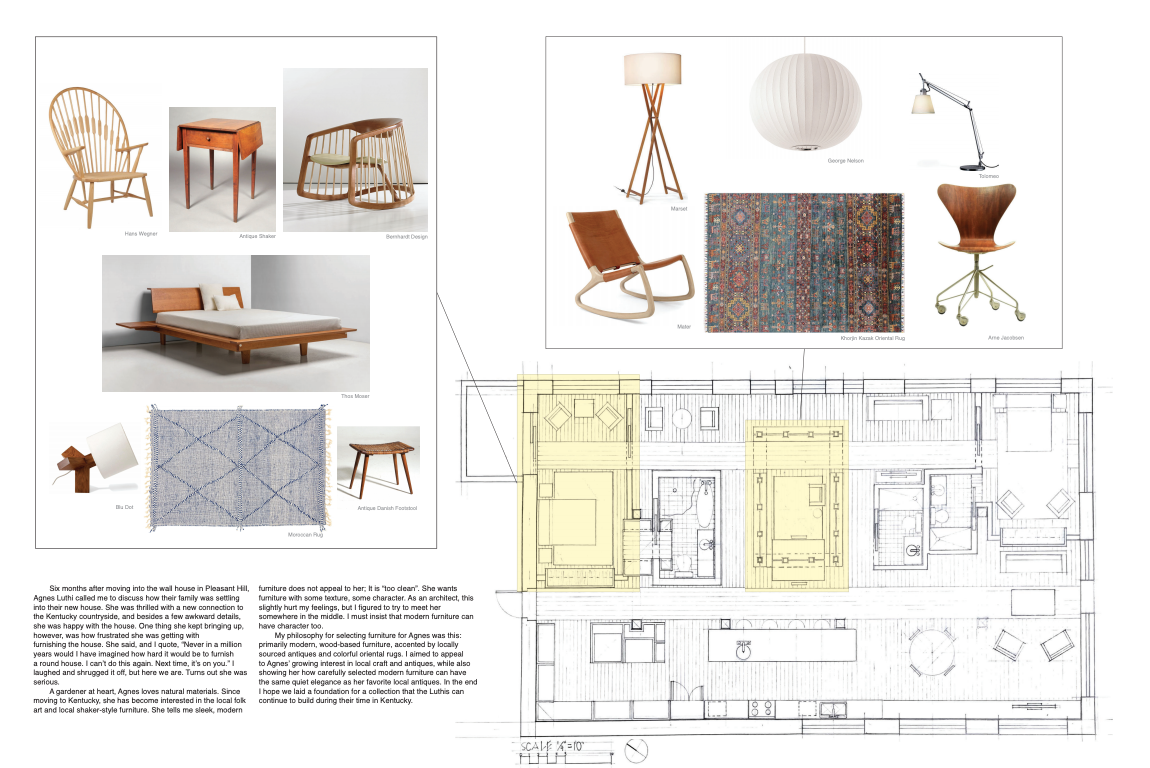

As a studio project, the renovation of an apartment instinctively raises questions of home versus house, domesticity versus dwelling, private versus public, and night versus day. They become key concepts to be translated within an urban context; an environment many students have not experienced prior to being a sophomore in college as many of them grew up in an American suburb. Renovation project A: second-year student final DESIGN plan

Renovation project A: second-year student final DESIGN plan

Any student engaged with this type of project will have an innate sense of familiarity with the subject matter of house or home, thus bringing their autobiographical experiences, their preconceptions, and, most importantly, their open mindedness to solving the studio’s brief. Renovation project B: second-year student final DESIGN plan

Renovation project B: second-year student final DESIGN plan

Above all, working out concepts between a physical entity (house) and connotations about emotional feelings (home), furthers the student’s inquiry into what contemporaneity living may mean. Learning about basic ideas of programming and zoning—separated but not isolated from each other—triggers design strategies that define rooms, while allowing other and more generous allocations of spaces to flow between assigned functions; practicalities that are often the touchstones of our lives and in desperate need to be reinterpreted in a contemporary manner.

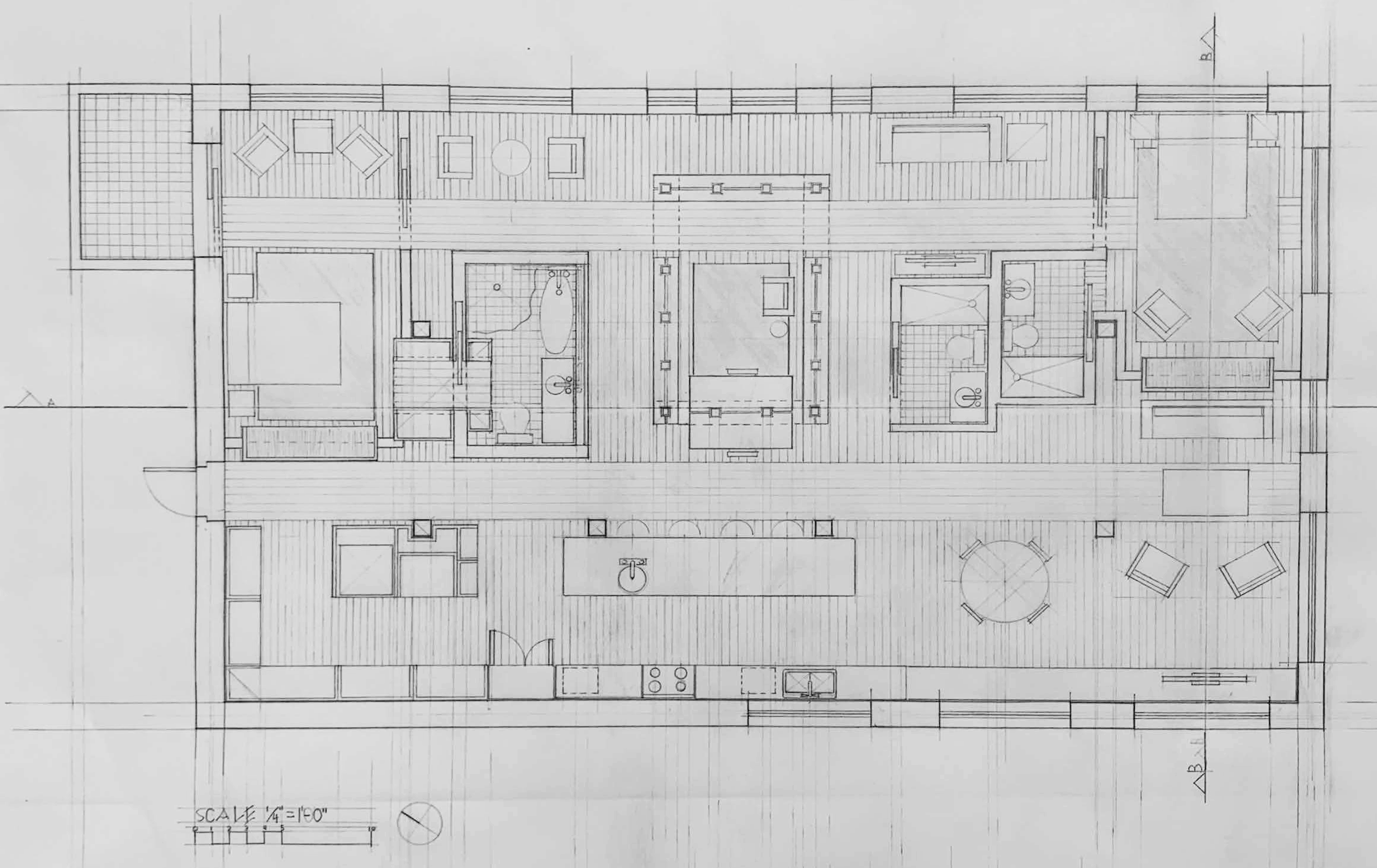

Renovation project C: second-year student final DESIGN plan

Renovation project C: second-year student final DESIGN plan

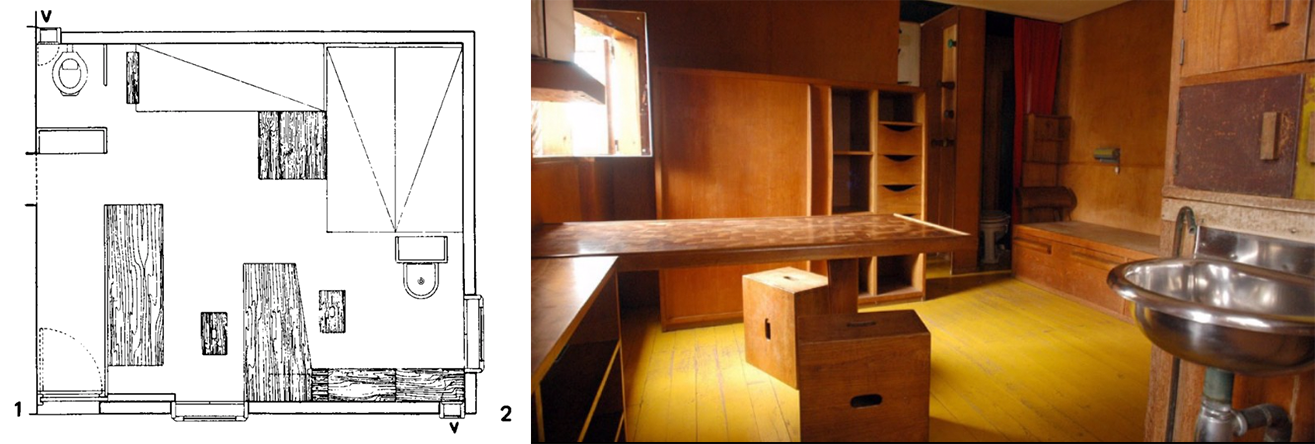

In his book Precisions (1930), Le Corbusier’s writes about The Undertaking of Furniture and underscores the importance that “The renewal of the plan of the modern house cannot be undertaken efficiently without laying bare the question of furniture.” The conversation between space and furniture is of essence for Le Corbusier and constitutes a key component in the loft project for the student’s understanding of how to experience space relative to the overall design.

As a student in architecture, I benefited from prompts that had some sense of reality and urgency, as the challenge was to bring conceptual and disciplinary thinking to a topic that seemed utterly mundane, a familiarity about living that often could have gone unnoticed if not addressed within a studio project. Google image: The 160 square feet Cabanon at Cap Martin, France (1951) by Le Corbusier

Google image: The 160 square feet Cabanon at Cap Martin, France (1951) by Le Corbusier

Furniture exercise

Armed with fundamental drawing techniques and an early ability to develop respectable to exquisite designs, many student projects are conceptually strong—coherent in their layout and based on a thesis, functional requirements, and the expression of the project’s value of usage—however, students often miss the mark when their designs need to suggest inhabiting space and place. Stated bluntly, to envision architecture must go beyond simply the design of spaces as voids; an emptiness often celebrated through the expressive and formal content of plans and sections.

This is particularly true when drawing with pencil on paper, but when students are ambitious and adept with digital software, renderings depict moments of their project with occasional ghost characters, yet, typically both iterative and final drawings never include furniture. If plans suggest the location of sofas, cabinets, tables, beds and chairs, they are simply seen as objects that express no real commitment and interest in understanding how spaces are inhabited. But let’s be honest, my students are only in second year and need to balance learning the rudimentary concepts of space making while, more importantly, having empathy towards the poetry of Architecture. Yet, is that statement an excuse to train them to conceive of architectural space absent of any type of furniture, thus denying how we inhabit the spaces we create?

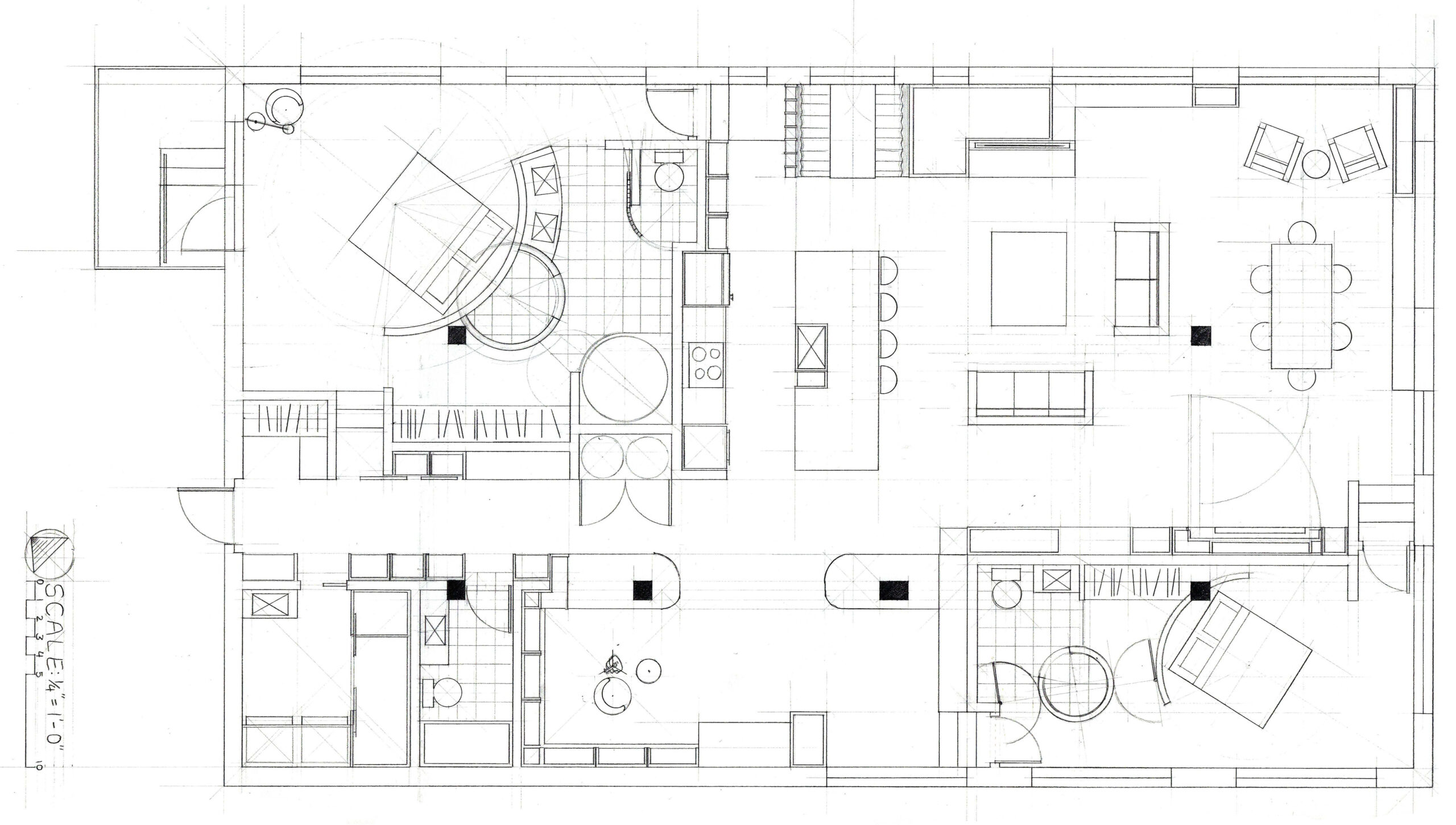

Renovation project A: second-year student final FURNITURE plan

Renovation project A: second-year student final FURNITURE plan

Space and furniture

To alleviate this shortfall of the dichotomy between creating space, representing space, and enabling space to be experienced, the loft project includes an exercise in choosing furniture. Designing space is one thing, but creating architecture is a different beast. For years, I have remained perplexed that far too often architecture students—after solid skill building in fundamentals of space making—lack the ability to integrate furniture in their designs. Not as a place holder that too often demonstrates a lack of understanding of customs and practices related to basic usages of a space, but as an understanding of how we live.

Be it exuberant or minimalist, the emptiness of space is far from what I consider to be architecture, a locus of emotional and physical experiences that compel us to socialize, interact and have our collective lives unfold among those intangible qualities based on conviviality, freedom, and fun. The placement and choice of furniture should not dictate how we engage with space, but rather suggest how layers of space provide ever-changing patterns of domesticity.

While furniture placement remains a minor part of a student’s overall design, especially as the education of an architect tends to avoid much attention to how users experience space, at the end of this exercise, I am pleased that after selecting furniture or designing custom built-in cabinetry, students remark that the exercise had a huge impact on their overall design. In fact, translating ideas into space should find a natural extension at the scale of furniture and case work. Renovation project B: second-year student final FURNITURE plan

Renovation project B: second-year student final FURNITURE plan

Question of domesticity…

In this exercise, selecting specific spaces or rooms, allowed students to evaluate how each space encompassed different human needs. Whether private or public, day or night zones, contemporary functional boundaries tend to blur traditional distinctions, thus raising the question about what encompasses the notion of “feeling at home?” Case in point, armed with our laptops, we settle into our neighborhood Starbucks and recognize that beaten leather sofas, accompanied by zones created by lighting which is often key to the store’s identity, reflect a surrogate living room that enhances “the human connection made over a cup of coffee and [reflect] the communities that they serve.” This urban ubiquitous backdrop—a companion to its patrons—is all about the interiors, the setting in place of a frame for individual and collective lives to momentarily unfold.

Like in most loft projects where the architectural shell is banal, the need to define spaces or fields of space within the existing confines obliges students to think differently, and, most importantly, to not valorize shape over form. For me as an educator, this observation has some immediate consequences, in particular in terms of learning objectives that were set in place for this project. Renovation project C: second-year student final FURNITURE plan

Renovation project C: second-year student final FURNITURE plan

Three thoughts

- First, for most architecture students, interior design issues are not self-evident, because often they are not addressed throughout their tenure. But when approached in an honest manner, the appetite and interest in interiors stimulated by including furniture, often suggests for students that a richer environment based on the life of the inhabitants—the idea of home versus the idea of house—gives their design renewed meaning.

- Second, choosing furniture eventually becomes second nature as students learn how to move between scales, and begin to understand how the integration or development of cabinetwork construction drawings can affect the overall scheme of the project. In other words, while “space” may seem finalized for most students, the addition and placement of furniture suggests minor but important adjustments of the plan, thus enriching the overall parti of their project. Whether the furniture and its placement is forceful or self-effacing, students slowly gain an appreciation that space is “defined by human actions, not bricks and mortar.”

- Third, architecture does not have to carry the sole responsibility to make great spaces. The combination of multiple talents from various disciplines, the choice of furniture, lighting, well designed built-in cabinetry, choices of wall coverings and selection of art, are many aspects of a project that weave practical and emotional needs into what we can call home. By the end of the project, students understand that a conceptual attitude can be developed at multiples scales, and most importantly be inclusive of many disciplines.

Conclusion

In conclusion, to provoke the students to frame their design and, in particular, the selection of furniture, I asked them to write a brief essay providing insight to their client’s character. Of course, many of these essays reflected the students’ own personality, but it was a way to start the dialogue between student and client, or more precisely between student and themselves.

This agenda of both the design of a loft and the choice of furniture, promotes an approach where the human experience slowly becomes increasingly important in the students’ attitude to space making. Giving priority to this way of thinking rekindles a Vitruvian definition of architecture by setting the human being at the center of any design move. Questions such as how will they inhabit the loft, what will they do in the space, and how will they experience the apartment, become essential components in defining the design prompt; a response that proposes an architecture of atmosphere, feeling, and character.

To quote Ilse Crawford, founder of the London design based Studioilse, “A well-being student is able to see things, places and experiences that need change and then design with a cool head and a warm heart—that is, combining reason with empathy.” This may seem trivial but perhaps for students it is a way to learn a more generous approach to discovery.

To view Loft renovation DESIGN projects

To view Loft renovation FURNITURE projects

Architecture Education: lessons from vernacular architecture—inventing versus re-inventing