Some time ago, a friend of mine mentioned an article in the New York Times Sunday Magazine on the work of Italian architect Carlo Scarpa (1906-1978). Her suggestion came at an auspicious moment as I was completing a second blog on the Venetian architect. Reading the article, the first paragraphs filled me with fond memories of visiting the featured apartment (Venice, 1962-63) that Scarpa had designed for his attorney Luigi Scatturin.

Some time ago, a friend of mine mentioned an article in the New York Times Sunday Magazine on the work of Italian architect Carlo Scarpa (1906-1978). Her suggestion came at an auspicious moment as I was completing a second blog on the Venetian architect. Reading the article, the first paragraphs filled me with fond memories of visiting the featured apartment (Venice, 1962-63) that Scarpa had designed for his attorney Luigi Scatturin.

Years before, when teaching in Venice, faculty colleagues of mine (Leonardo Ricci (1918-1994) and Maria Grazia Dallerba-Ricci (1936-2021) suggested that I visit Luigi Scatturin’s apartment as they knew the architect and his attorney. Implicit in their offer was their desire to mentor me, knowing first hand that Scarpa’s work was, for a young architect, a necessary rite of passage. I was certainly not going to miss this opportunity.

Image 1: Google images- Portraits of Carlo Scarpa

Image 1: Google images- Portraits of Carlo Scarpa

The context was timely, as during my studies, after Scarpa’s death in 1978 on a construction site in Japan, my school in Switzerland came to venerate the architect. Many of the architecture faculty at the EPFL shared how Scarpa approached a work of architecture that was so unique both spatially and constructively. I remember the emphasis given to his ability to work in a historic urban context, explore innovative spatial conditions within an existing building (i.e., preservation, renovation, restoration, and rehabilitation), and, perhaps most importantly—and certainly a consequence of the latter two attitudes—revive and incorporate centuries-old building techniques developed by craftsmen of the Veneto region; the locus of most of the architect’s completed work.

Venetian apartment of Luigi Scatturin

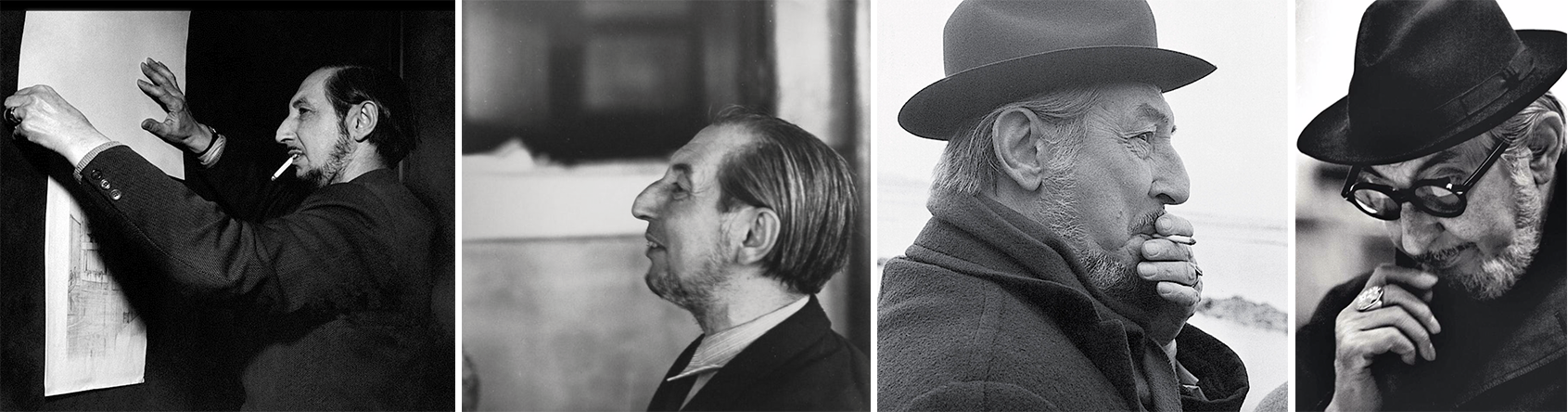

Scatturin’s apartment seemed both eccentric and extraordinary based on projects that I had already visited, including many of Scarpa’s interventions in Venice (Ca ’Foscari (1935-56), Galleria dell’Accademia (1949-59), Venezuelan Pavilion at the Biennale Giardini (1954-56), Museo Correr (1952-?), Olivetti Showroom (1957-58), Querini-Stampalia Foundation (1961-63), entrance to the school of architecture (1966-72, built 1985); and in the nearby Veneto region (Gypsotheque (1955-57), Castelvecchio (1956-64), Brion Tomb and Sanctuary (1969-78), and the at that time uncompleted Banca Popolare (1973-81) (Image 2, below).

Image 2: Google Images of above-named projects in chronological order left to right (1,2,4,5, and 8), and of author’s collection (3, 6, 7, 9,10 and large image)

Image 2: Google Images of above-named projects in chronological order left to right (1,2,4,5, and 8), and of author’s collection (3, 6, 7, 9,10 and large image)

The apartment of Scatturin

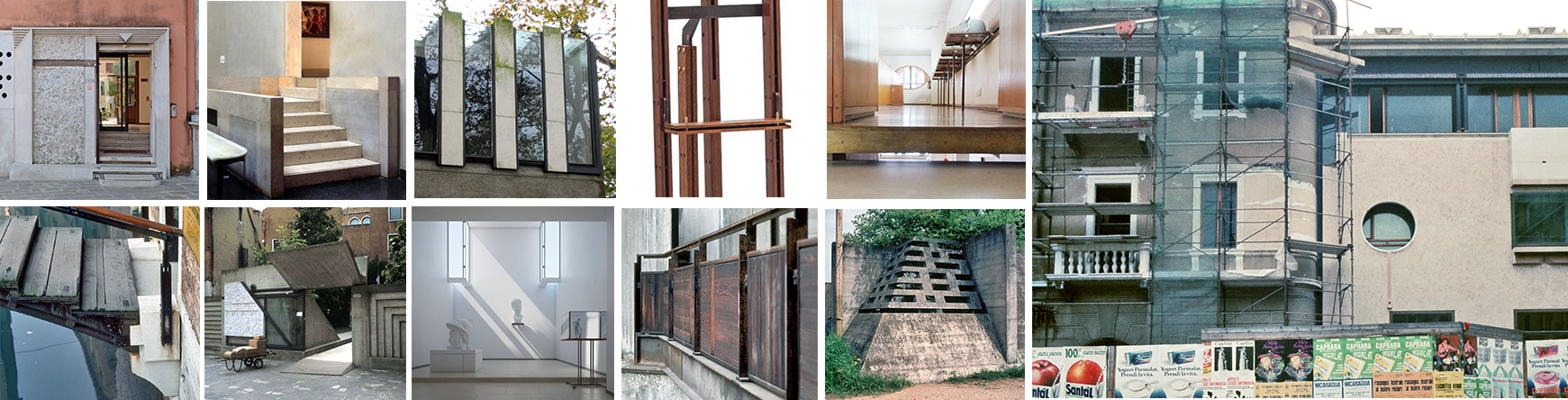

(below image 3) Upon entering Scatturin’s apartment, which was located on the upper floor, I knew that I was about to experience something very special. It was subtly divided in two parts, with his law office laid out at the front of the apartment (public), followed by the domestic realm in the back (public and private – the latter receiving ample light from all three sides). At first, I did not fully appreciate the layout, as my eyes were jumping around between dense and tightly orchestrated rooms, eventually focusing on Scarpa’s mastering of every nook and cranny in order to explore depth and volume through the refinement present in all of his details.

Despite that my visit was over two decades ago, I remember my curiosity was drawn to the numerous doors—treated differently as edges, transitions, passageways, and limits, all defining and anticipating the sequencing of rooms and spaces. Architects tend to celebrate spaces where rituals of life unfold, but here—because of the confining nature of the overall apartment—Scarpa developed a unique strategy by emphasizing transitional moments, celebrating them through a thickening of passageways, changes in elevations (ranging from one step to Scarpa’s celebrated ladder-stair leading to a narrow terrace overlooking the roofs of Venice), chicanes, and built-in furniture.

Image 3. Google images: Plan of the apartment for Luigi Scatturin with photographs showing location of interior spaces

Image 3. Google images: Plan of the apartment for Luigi Scatturin with photographs showing location of interior spaces

Scarpa’s design approach

This in-situ experience reinforced many aspects of my polytechnic education, one where intellectual curiosity and professional accountability were part of a robust pedagogical outlook. Case in point, in Scatturin’s apartment, the logic of construction was integral to the project, and never an afterthought to the ‘completion’ of the design. From concept to execution, Scarpa did not shy away from approaching basic problem-solving strategies in a poetic way; poetics understood according to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, “to encompasses both the arrangement of materials and structure.”

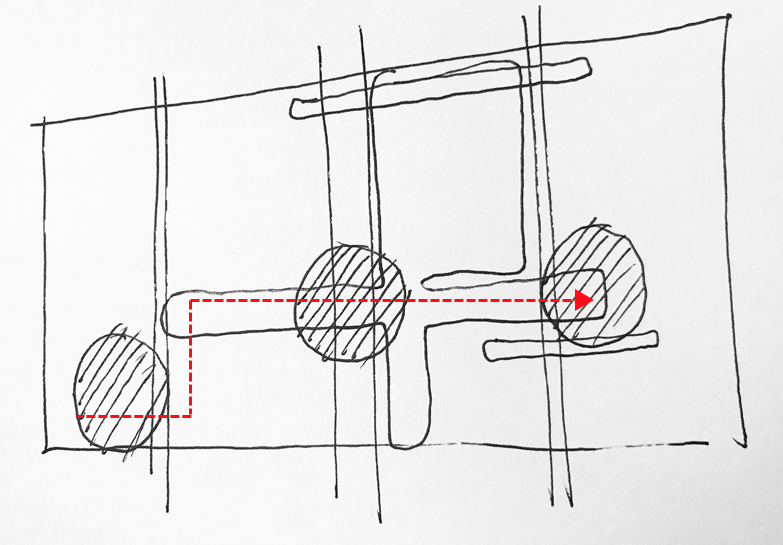

This visual and sensuous feast of belonging to something bigger than oneself was constantly reflected in Scarpa’s rich treatment of each surface, material, tonal texture, and color, all of them bathed that day in warm winter light which reflected off the floors, walls, and ceilings. Years later, I was able to set my eyes on the plan of the apartment and was reminded of the problem students often face: “of the[ir] ever-recurring error of confusing architecture with its image or any kind of scenography.”[1] Scarpa’s plan seemed straightforward and almost mundane, yet it was so architectural if one explored it, even if only on paper. His approach between public and private spaces unfolded within the confines of existing structural walls as an incredible concept. (below image 4) Image 4: Diagram of the conceptual layout of the apartment (author’s collection)

Image 4: Diagram of the conceptual layout of the apartment (author’s collection)

Celebration of tectonic moments

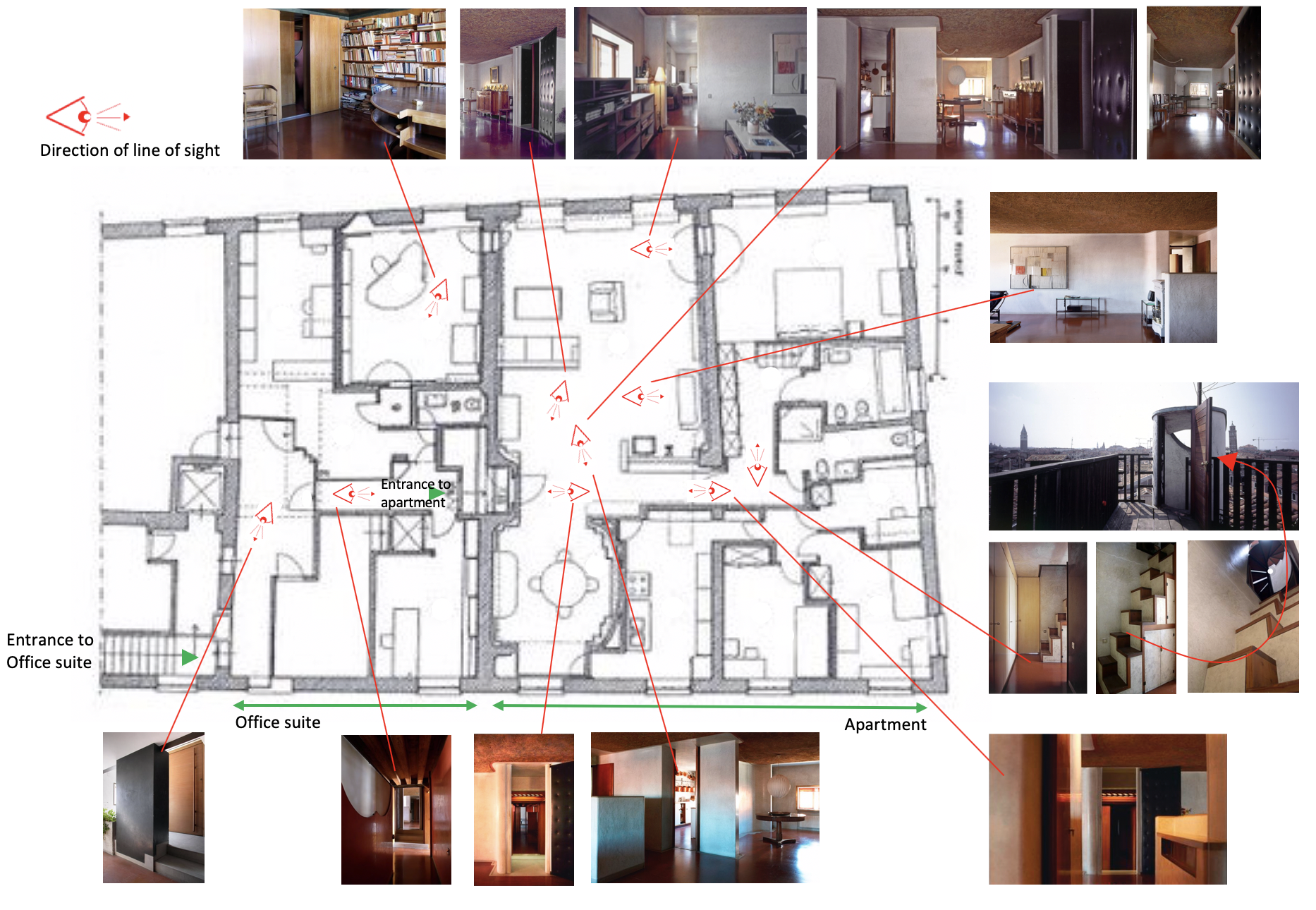

Image 5: joint details of Castelvecchio, Gypsotheque and Banca Popolare (author’s collection)

Image 5: joint details of Castelvecchio, Gypsotheque and Banca Popolare (author’s collection)

While I recognize that I am referring here to a deeply personal experience, I believe that the work of Carlo Scarpa should be part of any architecture students’ visual, spatial and constructive literacy. His work is known to hold an extreme position in defining spaces, one that few contemporary architects have mastered to this level of sophistication. Perhaps, because of his marriage of concept and execution, this manner of space and construction may be part of the past. More realistically, perhaps the role of the architect has changed in today’s complex and more democratic world; we are no longer specialists but generalists.

Nevertheless, when visiting any of Scarpa’s projects, one is quickly drawn to the way he connects created spaces (content) with their edges (container). What is so compelling in this approach, is that he practiced a quasi-obsessive complicity towards customized practicality, flexibility, and ergonomics, all seamlessly reinforcing each other. There was an originality, daring, and intelligence in how these spatial qualities were balanced; and it was always with the utmost elegance and sense of poetry.

It is well documented that the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, the European Wiener Werkstätte, and the Dutch pictorial Neo-Plasticism movement had strong influences on Scarpa’s work. Of course, beyond his love of Japan. Interpreting these precedence, Scarpa understood how to elaborate on new spatial conditions by working within a novel approach of juxtaposing natural materials, colors, and textured finishes. Above all, he excelled in reviving and incorporating traditional craftsmanship in a manner that would give depth and vibrancy to each of his ‘rooms’ (i.e., Marmorino Veneziano’s type of plaster or stucco).

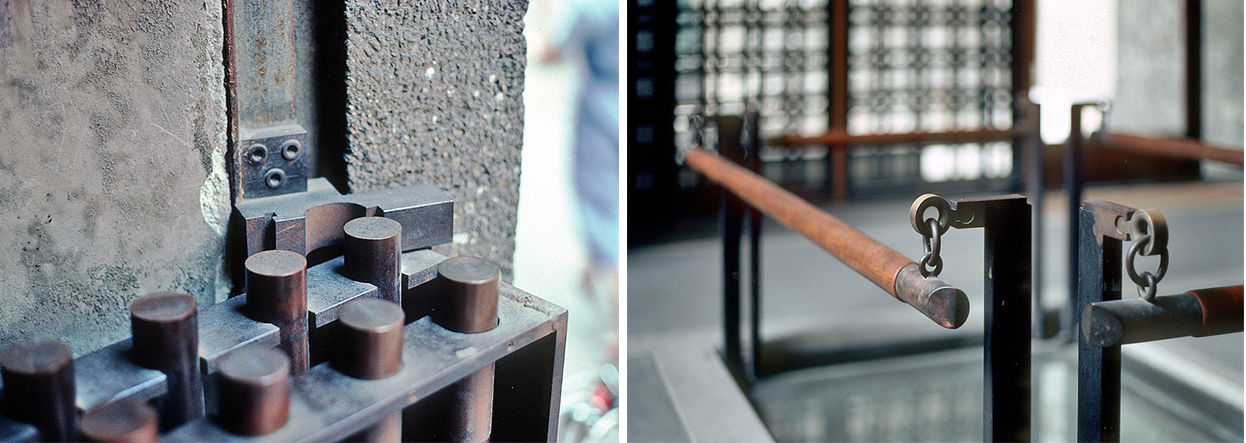

Image 6: joint details of the university entrance, and Castelvecchio (author’s collection)

Image 6: joint details of the university entrance, and Castelvecchio (author’s collection)

(above images 5 and 6) While working with a joint that is part of any architect’s syntax, Scarpa used this device at multiples scales, always celebrating a structural moment, a window or passageway detail, or giving reverence to an existing wall. In many of his details, Scarpa showed us how construction anticipated how materials would move and age. He was also a master at letting us know how craftsman fabricated the detail, thus enabling us to understand the various gestures of how materials were removed, added, and finally assembled (below image 7).

Conclusion

While Scarpa’s work is emblematic of a past which revers craftsmanship as well as the human experience of inhabiting places, I believe there is room today, particularly as we educate a future generation of architects, to study his work and regain a culture of construction.

Image 7: detail of the entrance portico at the Gavina showroom in Bologna and balustrade at Castelvecchio (author’s collection)

Image 7: detail of the entrance portico at the Gavina showroom in Bologna and balustrade at Castelvecchio (author’s collection)

Image 8: Corner details of the chapel and exterior wall at Brion Tomb and Sanctuary (author’s collection)

Image 8: Corner details of the chapel and exterior wall at Brion Tomb and Sanctuary (author’s collection)

Image 9: Step details at Querini Stampalia and the Venezuelan Pavilion (author’s collection)

Image 9: Step details at Querini Stampalia and the Venezuelan Pavilion (author’s collection)

Image 10: Abutment detail of the steps of the Querini Stampalia bridge as it touches the exterior facade (author’s collection)

Image 10: Abutment detail of the steps of the Querini Stampalia bridge as it touches the exterior facade (author’s collection)

Image 11: Stair at Castelvecchio expressing to the left a system in suspension/cantilever and to the right a system of compression (author’s collection)

Image 11: Stair at Castelvecchio expressing to the left a system in suspension/cantilever and to the right a system of compression (author’s collection)

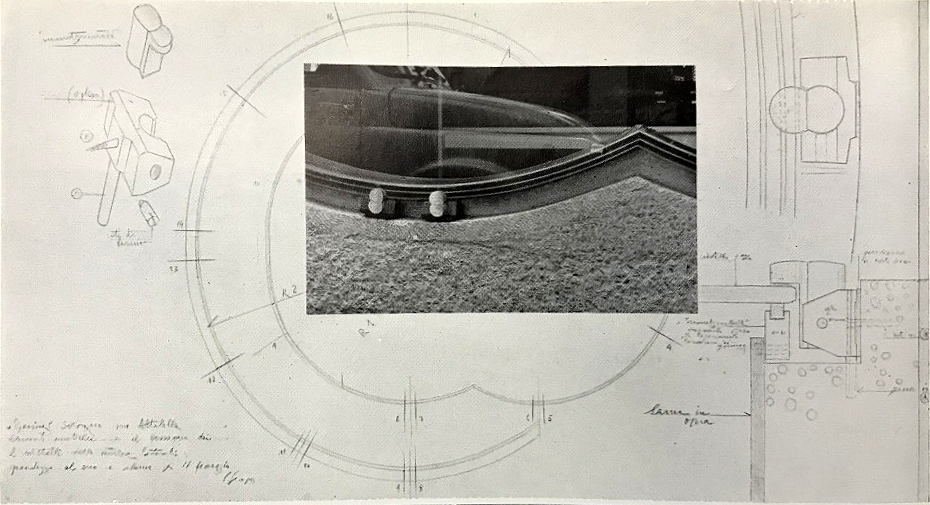

Image 12: Google images- Vesica window developed for the Gavina Showroom in Bologna.

Image 12: Google images- Vesica window developed for the Gavina Showroom in Bologna.

Image 13: Google image- construction detail of the Vesica window developed for the Gavina Showroom in Bologna.

Image 13: Google image- construction detail of the Vesica window developed for the Gavina Showroom in Bologna.

Image 14: Layering of history at the University entrance (author’s collection)

Image 14: Layering of history at the University entrance (author’s collection)

New York Times article: Bollen, Christopher, 02.18.2020 on Scatturin’s apartment

Galleries of other works by Carlo Scarpa

Carlo Scarpa, Cemetery Brion Vega

Carlo Scarpa, Castelvecchio

Carlo Scarpa, Giardini

Carlo Scarpa, Gipsoteca

Carlo Scarpa, IAUV Architecture

Carlo Scarpa, Querini Stampalia

Carlo Scarpa, Olivetti Showroom

Carlo Scarpa, Banca Popolare

Carlo Scarpa, Venezuela Pavilion

Blogs

The following blogs reflect in-situ analysis of specific aspects of Carlo Scarpa‘s work. All images are part of the author’s collections

Carlo Scarpa, Venice entrance pavilion

Carlo Scarpa Gavina Showroom in Bologna. Part 2

Carlo Scarpa Gavina Showroom in Bologna. Part 1

Carlo Scarpa and detailing

Carlo Scarpa Gipsoteca in Possagno, Italy

Additional images on the works of Carlo Scarpa with additional links

[1] Frampton, Kenneth, Carlo Scarpa and the Adoration of the Joint in Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture, Cambridge: MIT Press, Third Edition, 2001, p.309

What a wonderful essay on one of my all time favorite architects & I couldn’t agree with you more ! I believe he needs to be brought into the forefront of the early educational environment of todays architectural student as it may help to bring back the true art & soul of our very special craft.

I could not agree more with you as an international architecture may well be at the end of its vision. More local driven re-inventions may be the task of a new generation.

Thanks for your insightful comment.