Hong Kong: the history of Central Market. Since ancient times, public markets—coined mercatus in Latin, which means trading, dealing or buying, as well as the physical place where those activities occur—have served as the identity and social lifeline for countless cities and towns. Food markets in particular have played a significant role as community-gathering places.

Often, over time, vendors and loyal customers form a bond beyond simple transactional activities; engaging in family-like exchanges. In other words, markets (e.g., souk and bazaar), and their physical expression are what I like to call a civic and cultural experience for the locale’s population. Although they also serve as trading points from town to town and between communities.

Markets

As a physical place, markets have taken on a number of formal attributes. First, since ancient times markets have been held in open-air spaces that typically not only activate the area they use, but form a connection with the immediate surroundings. For example, in the Italian city of Verona, the market extends throughout the Roman castra with its pedestrianized streets forming a network between civic, religious, and commercial plazas.

Another setting for markets was the enclosed temple of consumption (e.g., Trajan’s Market in Antique Rome). Here, were numerous food stalls, which were eventually in the 19th century housed in iron and glass structures of engineering prowess (e.g. the Boqueria market in Barcelona (Image 1, above), Spain, or the Singapore Victorian era Telok Ayer Hawker food court (Image 2, below)). Between open and enclosed spaces, market types have been extensively documented and include market squares, market halls, food halls, and sadly, today’s online marketplaces.

I am fortunate to have visited many famous historic markets, and those that I remember are considered landmarks in their own right. They offer a cornucopia of local and international gastronomic products as well as serving as a place to enjoy a glass of regional wine or small epicurean bites.

When thinking of markets of all kinds (e.g., food markets, farmers’ markets, dry markets, wet markets, wholesale markets, and flea markets), I think fondly of the stalls of the neo-Gothic fish market and Rialto fresh produce market in Venice; the Boqueria in Barcelona; the Place des Lices in St Tropez with its Provençale delicacies such as breads, pastries, cheese, sausages, flowers, olives, spices, herbs, fruits and vegetables; and two celebrated flea markets, the Nashmarkt in Vienna, and the Marché aux Puces of Saint-Ouen in Paris.

I also have particular memories of the market in Lausanne as it meanders through the medieval section of the city; the Chandni Chowk in Delhi with its narrow lanes bursting with life; the Egyptian and spice market in Istanbul near Galata Bridge; and early morning visits to the Tsukiji Fish Market in Tokyo. The Grand Bazaar of Isfahan is one that I hope to eventually visit. Each of these markets have, through their locations, come to define a particular aspect of the life of their city. Over time, each of these markets has allowed me to witness the commonalty that is the spectacle of human civilization.

Les Halles of Paris

Of course, as an architect, I wish I remembered the famous Les Halles de Baltard in Paris (named after French architect Victor Baltard), which was a monument in its own right, equal to the Eiffel Tower or the historic structures along the great Parisian boulevards. With the curse of time, Les Halles was heartlessly demolished in 1973, to be replaced by consecutive monstrosities of non-descript underground multi-story shopping centers.

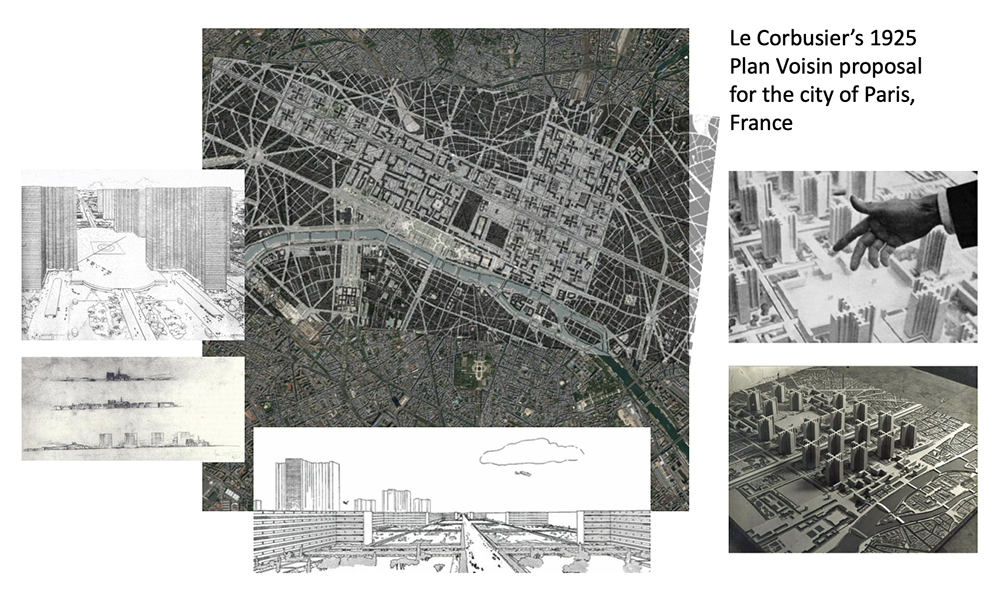

Let me also acknowledge that blocks of medieval fabric were removed in the heart of Paris to create the famous Les Halles, thus the question of what deserves to be preserved might seem relative and selective! Although this demolition was nothing compared to the magnitude of the Plan Voisin proposed by Swiss architect Le Corbusier who envisioned the demolition of the major historic center of the French capital to implement his megalomaniac urban vision (Image 3, above).

I will also unequivocally state that, for me, what was to become the Forum des Halles (Image 4, below) represents one of the worst pieces of French contemporary architecture. In fact, for many critics and die-hard Parisians, the removal of Les Halles was “considered one of the worst acts of urban vandalism in the 20th century,” and represented the wrong side of an argument defined by Le Corbusier’s “quarrel of the Ancients against the Moderns;” of course with Le Corbusier being on the ‘wrong’ side of the Moderne.

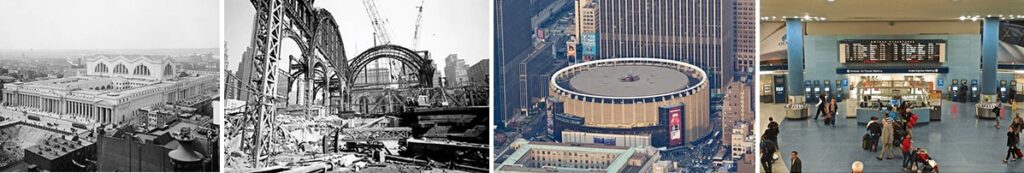

Perhaps the story of Les Halles is reminiscent of the destruction of the iconic Pennsylvania Railroad Station in New York City (Image 5, above) barely a decade earlier. It was replaced by a ghastly pseudo-functionalist sub-terranean train terminal with an equally un-urban tower overlooking the new Madison Square Garden sports center. All in the name of modernism. At least this act of destruction led to international outrage that galvanized the public to see this loss “as a catalyst for the architectural preservation movement in the United States,” and, with it, a growing public awareness of preservation issues, leading to the establishment of New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1965 (Image 4 and 5, above).

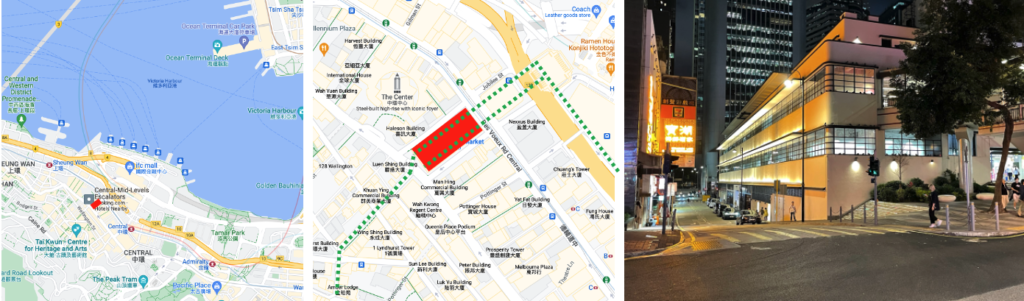

Central Market; its location

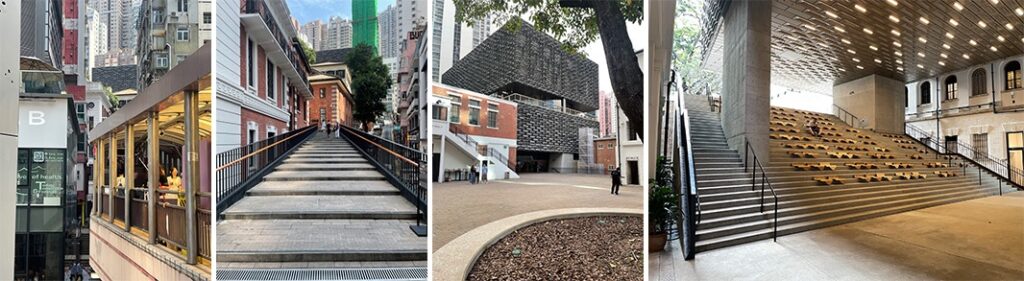

On a more joyful note, and certainly at a more modest scale, I recently discovered the renovated and revitalized Central Market in Hong Kong; which is situated on the island of Hong Kong, one of my most cherished cities. During a recent trip, not once or twice, but three times I returned to this “wet” market, enamored by its architecture and its two main interior staircases; all the while remaining confused by the lost dialogue of what Louis I. Khan would term the container or contained in architecture.

I mention “wet” market as this is the terminology used in the Fragrant Harbor (Hong Kong). I understand that this expression was coined in Singapore in the 1970s to define a market that sold fresh foods and perishable goods; contrary to a dry market that sells durable goods such as those found in emerging supermarkets.

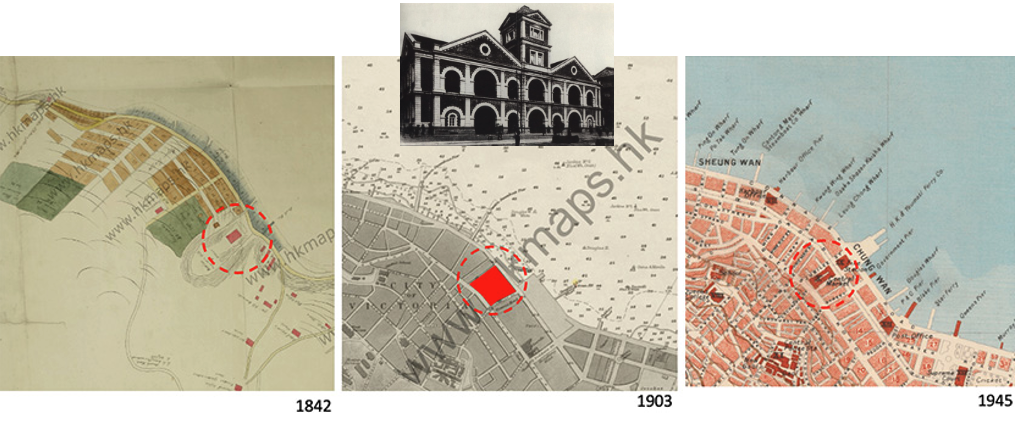

Built in 1939, the current Central Market is the 4th generation of a market type. Under the current listing of Hong Kong’s Antiquities and Monuments Office (AMO), the building is a Grade 3 historic building. This rating system means that structures are “Buildings of some merit; preservation in some form would be desirable and alternative means could be considered if preservation is not practicable.” Of preservation interest, the two other grades of historic buildings are Grade 2 (“Buildings of special merit; efforts should be made to selectively preserve”), and Grade 1 (“Buildings of outstanding merit, which every effort should be made to preserve if possible”).

The 4th generation of markets

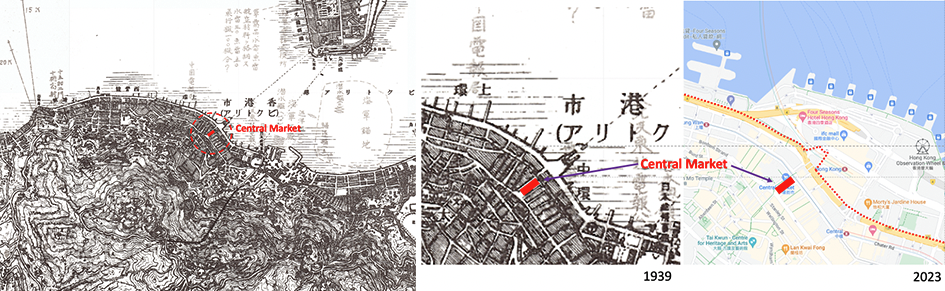

Central Market’s 4th generation market has physical and cultural antecedents. To look into urban precedence, I like researching antique maps to find more about the history and location of buildings (e.g., Sanborn maps in the United States). In my study of Central Market, I discovered that the market was initially not far from its current location fronting Queen’s Central Road.

With the exception of a short relocation to Queensway (east of the present location), the first indication of Central Market’s situation can be traced to an 1842 map (Image 7, above), where Queen’s Road Central is formalized. Constructed by British Royal engineers between 1841 and 1843, it is the oldest road built that tracked the original shore line.

The market’s urban position within the emerging city’s morphology was as a stand-alone building that occupied an entire city block. It had no adjacent buildings, and the natural cross ventilation would give Central Market a leading position as a new generation of market type. Also, amenities included: natural ventilation through operable windows and a centrally located spacious atrium; high ceilings; modular stalls with adequate drainage; clean hot and cold water supply; and basic sanitary services for soil removal to maintain the operation of clean stalls (e.g., chicken slaughter rooms were adjacent to running water). These were some of the modern hygiene policies established for Hong Kong’s newer markets.

These guidelines were mainly in response to the the city’s 1894 Plague Epidemic, which led to the creation of the second generation of markets as proposed in the 1903 map (Image 6, above). The necessity of these guidelines reminds me of the ongoing complicated and contentious theories surrounding the origins of Covid-19 which involve tracing it back to the live-animal market in Wuhan, China where hygiene policies may have been not observed.

Since its inception, the market that will become Hong Kong’s Central Market was not only near Tai Ping Shan—which is the oldest Chinese neighborhood and ground zero of the 1894 plague—but each iteration of the market faced Victoria Harbor to allow direct access to goods ferried-in from the mainland, including those that arrived by train at the old railway station in Tsim Sha Tsui (demolished in the late 1970s).

In fact, the 1939 map clearly indicates Central Market’s direct access to the H.K & Yaumati Ferry Co. landing (dashed lines connecting the west side of Kowloon, Image 6, above middle). Of course, the market’s ability to directly access the waterfront no longer exists due to subsequent land reclamation projects completed on the island side of Victoria Harbor.

Central Market and its urban connections

In 1994, Central Market was a joint between the complex footbridge network of the Central Elevated Walkway and the Central-Mid-Levels Escalator completed in 1993 – the world’s “longest outdoor covered escalator system.” The escalator formed an umbilical cord spanning the steep and hilly terrain between Queen’s Road Central and the mid-level of Hong Kong, ending at Robinson Road (Image 8, middle).

The 1982 recommendation to build a north-south “escalator assisted pedestrian route” (Image 9, above) designated Central Market be replaced by a new bus terminal. Thankfully that didn’t happen. Of note, today’s vertical escalator network branches off at Hollywood Road and Old Bailey Street, and includes an entrance to the former central police station compound; since 2018 transformed into the Tai Kwun Centre by Swiss Pritzker prize laureates Herzog et de Meuron (Image 10, below).

Examining the history of the Central Market was initially because it is a Bauhaus building. Now, I need to return to that point in more depth in a future blog.

Additional content about the city of Hong Kong

Hong Kong: Bauhaus style Central Market

Hong Kong: a lesson in stairs (Central Market)

Bathroom at the Novotel in Hong Kong

Hong Kong: a lesson in stairs (Billie Tsien and Tod Williams)

Hong Kong: a metropolis of contradictions

Blue Bottle Coffee: Hong Kong

Hong Kong Shopping Mall