People’s Park Complex in Singapore, Part 1. There are some buildings that at first do not strike you. In fact, their demeanor reflects your preconception of what is good or bad architecture—an attitude that is far too often spontaneous and not rational enough to constitute a meaningful critique. For me, this was my dislike of the People’s Park Complex in Singapore.

“…a brutal high-rise slab on a brutal podium,” that is “in fact a condensed version of a Chinese downtown, a three-dimensional market based on the cellular matrix of Chinese shopping —a modern-movement Chinatown.”

Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, S,M,L,XL

This was because I did not understand the cutting-edge nature of the project when it was built. Added to this, brutalist expression is rarely part of an aesthetic lexicon, or model of life, that I espouse as an architect.

Fast forward to today as those first impressions date from ten years ago. During a recent trip to the island nation of Singapore—which is, in fact a city-state—I fell in love with the same building I had originally dismissed. While I’m still not convinced about its visual interest, I had in the interim researched the significance of the complex within the landscape of Singapore’s efforts in its early nation-building days.

Singapore post 1965

Singapore became an independent country in 1965. Prior to that, Singapore joined Malaysia from 1963-1965, after gaining self-determination from a forty-year British colonial rule in 1949—not to mention a terrifying two-year Japanese occupation during World War II (1942-1945). After independence in 1965, young architects who had been mostly trained abroad were now also educated locally and they strived to make their mark by building a cosmopolitan environment in what was considered a post-colonial atmosphere of promise. Architecture had a role and was not going to remain a silent participant in the new government’s social program.

Talented architects such as the trio of William Lim, Koh Seow Chuan, and Tay Kheng Soon formed the Design Partnership Architects & Planners (later morphing into DP Architects Pte Ltd). In 1967, they were entrusted with the design of the People’s Park Complex (Image 1, above). Interestingly, Tay Kheng Soon studied at the Singapore Polytechnic school of architecture (now NSU) under Lim Chong Keat, who introduced the Bauhaus’s instructional methods to young local architects.

Singapore architecture

Within the context of building a new Singapore, modernism was commonly understood across Asia—at least at the beginning—through the teaching methods of the Bauhaus. But now architects felt that a true Singaporean architecture needed to be balanced with national building traditions and express the idioms of design that responded to their tropical climate. Buildings needed to acknowledge in a spatial manner, to elevated temperatures, high humidity, monsoons, and strong sunlight, with design strategies that enabled heat dissipation, provided shade, allowed appropriate rainwater drainage, and captured natural cross ventilation to regulate temperature.

While looking to the West to contextualize their future legacy, many young Singaporean architects sought to design structures that expressed the identity of post-independence nation-building. The practice of architecture and the ensuing buildings reflected a tangible embodiment of that vision, all the while being influenced by the ideals expressed by the post World War II rebuilding of Europe (aka, the later work of Le Corbusier in India that privileged climatic determinants, and most importantly, socio-cultural factors).

This attitude meant that many of the younger generation no longer wanted to build in a colonial style. The new architecture had to be daring, bold, rational, and part of a social development sponsored by the new government. Thus, the importance of representing how this new nation wanted to be part of something big; architecture needed to embody the sense of de-colonization by building a model of life for a new world.

And yet, new buildings based on tropical climate control were, according to Maxwell Fry (British architect who practiced with Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, and Pierre Jeanneret), simply a “dialect of internationalism.” Beyond the obvious references to the International Style that was based on an austere formalism with social idealism, there was an expression—or tribute—in many of the new buildings in Singapore of a style called brutalist architecture (aka, the Japanese Metabolism movement), all along precepts of the 8th CIAM Conference (The “Heart of the City” emphasizing a city for the pedestrian), and Team 10’s notion of urban reintegration (“providing a continuous space from residence to shops to the exterior and rest of the city”).

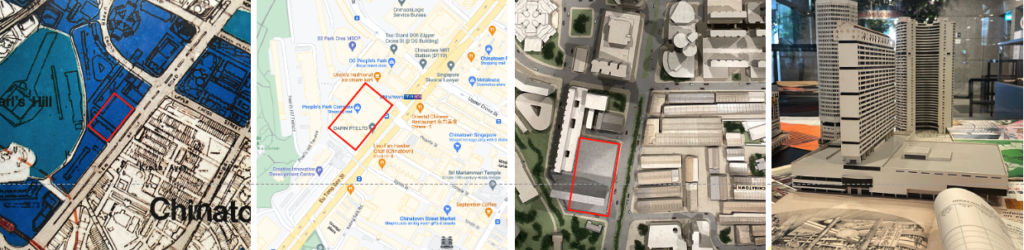

These world-wide influences were powerfully reflected in the built work of the iconic People’s Park Complex (1970-1973). Accompanying this spirit of modernism, the architecture of the building would become integral to urban planning through its example of a compact, high-density, and multi-use city formed by small neighborhoods within the vertical subdivision of floors in clusters.

Site strategy

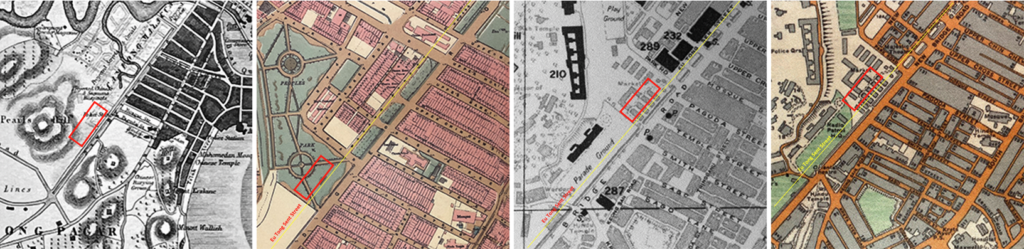

The People’s Park Complex is situated on the former Pearl’s Market site adjacent to People’s Park and Pearl’s Hill Park that contained both a reservoir and the upper and lower garrison barracks that accommodated the Sikh Contingent of the Straits Settlements Police Force. In 1966, a fire destroyed the bustling market of makeshift shops (Image 7 left, below), leaving prime real estate for the design of a new building type based on the reinvention (or hybrid integration) of housing, commercial, supermarket, offices, food and beverage (mostly hawkers’ style which are street food vendors that have small store fronts), and, not least, a car park.

These functions, to the exception of housing, took place in the plinth of the newly designed building (ground floor and five stories of shopping). Of note, and reflecting the city’s commitment to its citizens, “the new multi-use development complex would go on to rehouse many of shops that were affected by the 1966 blaze.”

Traditional shophouse typology

The People’s Park Complex builds on the preexisting South Asian shophouse typology (Image 3, above) that combines both residence and business under one roof (a prototype of a home-office-store). The pedestrian level of the traditional shophouse features a uniform arcade (i.e., a covered sidewalk, portico, verandah, or colonnade) called a five-foot waythat was established in the 1822 town plan for Singapore; an urban morphology that required for a subdivision “of the land into smaller regular lots” (Image 8, below).

The sheltered space of the portico protects pedestrians from the unbearable glare of the sun, humidity, and from the torrential rain of the monsoon seasons. Beyond that, the public walkways have an urban purpose that suits the local climate, they functionally and socially link shophouses to each other through the definition of a continuous urban space for store owners, customers, and pedestrians (Images 5, 6 and 7).

The shophouse lots were narrow where they faced the street. The arcades provide a natural extension of each store in which to display merchandise or, for additional covered outside seating areas (Image 5. Above, second left). On a side note, the neighborhood of Little India in Singapore has a similar configuration for its stores, but like in the Indian city of Jaipur, the arcades often become arduous to negotiate as vendors have cannibalized most of the public realm for use in trade, movable stalls, storage, and even temporary living spaces (Image 7, above).

The shophouse typology creates a distinctive character for the cityscape of many Singaporean neighborhoods, and are a legacy of the Straits Settlement building style found throughout the city—Straits Settlement signifying “a group of British territories located in Southeast Asia.”

Other blogs of interest about Singapore

People’s Park Complex in Singapore. Part 2

People’s Park Complex in Singapore. Part 3

National Museum in Singapore, Part 1

National Museum in Singapore, Part 2