Beyond the sublime postcard-like views of Switzerland, there are few European landscapes that have moved me more than those I have encountered while traveling in Italy. One of the most scenic and memorable parts of the Italian countryside is located in the north east, a region called the Veneto, which spans the medium-sized cities of Vicenza, Verona, and Padova, ending with Venice.

The Veneto region

The latter city is built on the Laguna fronting the Adriatic Sea; a city often referred to as la Serenissima. While the Dolomites offer a majestic northern backdrop to the string of cities, it is not the region’s visual beauty that so captivates me, but how a cultural attachment and historical identity to the land is revealed through man’s imprint on the countryside (Image 1 below).

Over millennia, the region’s land was cultivated using ancestral gestures, and owes much of its current physiognomy to family and political subdivisions that took place during the sixteen and seventeenth centuries—primarily resulting from the feudalization of land ownership. Later, during the nineteenth century, further territorial modifications were brought through cadaster partitioning. In the Veneto, this was a result of the need for land drainage and irrigation management. The history of working the land has allowed small and large farmsteads to co-exist, giving the region is distinctiveness.

The landscape of the Veneto is neither majestic nor sublime. And yet, because of its ordinariness it represents a deeply agrarian culture punctuated by human settlements. During the sixteenth century, much of the Veneto’s farmland was transformed into rural estates through consolidation of the agricultural system. The homes built for noble families to supervise production—they remained closely connected to these rural holdings even when living in the city—resulted in the villa, an architectural ideation of a way of living; a model of life. This building type resulted from the artistic expression of a variety of talented craftsmen and architects and have become world famous, especially for architects! (Image 2 below)

The villas of the Veneto remain easily recognizable due to their classical attributes: a front portico echoing the language of antique Roman temples, and a site strategy that took advantage of “views that are near, some further, and others that finish on the horizon.” The villas represent an architectural maturity that differentiates itself from farm houses, the latter often seen in some kind of constant decay

An Italian journey by train

This pleasure of viewing the panorama of these historical interventions is particularly true when experienced by train between Milan and Venice. After leaving the landmark terminal of Milano Centrale, where the sounds of the passengers and train announcements echo throughout the Roman-inspired entrance hallways; across the exquisite floor mosaics; and onto the vaulted nineteenth-century engineered ceiling, one traverses endless, monotonous Milanese suburbs (e.g. Milano Lambrate) before finally emerging on the Plain of Po, which leads to the east and the Veneto region.

During my numerous trips to Venice, I favor a journey that does not involve high-speed trains such as the iconic, evocatively-named Alta Velocità, Direttissima, or Pendolino. I have always enjoyed the ride on a typical InterCity, or even better, a slower regional train. I remember traveling years ago in a compartimento that accommodated six passengers on comfortable seats covered in fabric, my gaze focused on the campania which was generally accompanied by what I call an Italian national sport.

An Italian national sport

During many of my train travels—and after a customary buongiorno to incoming passengers—I enjoy listening to their benign conversations, which rapidly became spirited, and often ended up as quarrels about governmental scandals and bribery in Rome, and who is truly entitled to be prime minister; as they change so regularly on the Italian peninsula.

Usually, the conversations extend to deeply rooted historical and regional attitudes regarding the North (i.e., stereotype of a more Alpine, hardworking, and business-oriented society) and how they should secede from the South (i.e., stereotype of a more Mediterranean culture perceived as being more laid back); often without ever mentioning the island of Sicily, as if it was suddenly part of another country. When the topics became about men’s pride, they argued passionately about the most iconic actresses of Federico Fellini’s Cinecittà (i.e., Gina Lollobrigida versus Sophia Loren, Anna Magnani versus Giulietta Masina—the latter was Fellini’s wife).

When the length of the train journey permits, and additional passengers having joined the lively discussion, I am amused by the arguments about the Vatican and, in former years, about the German Pope Benedict XVI, or the bizarre and rocambolesque explanations regarding the death of Pope John Paul I—who officially died of natural causes, but it is rumored that his death was assisted by the Cosa Nostra.

Needless to say, all of these melodramatic discussions are inescapably accompanied by a well-versed lexicon of the passengers’ gesticulations left and right—hands and fingers pinching in tandem with universal facial expressions. I guess that this gives each passenger an unsurpassed satisfaction for nonverbal communication—an art form easily recognizable on the Italian peninsula. Well, maybe Indians of the sub-continent are close to Italians, both honing a language of gestures that I so much love (Image 4 above).

All of these conversations are so comedic and part of the stereotype referred to as fare la bella figura (to make a beautiful figure): where keeping up appearances in the public realm (also in Great Britain!) remains key to any argument; not simply leaving a good impression, but making a beautiful one with style!

The marvels of a Tuscan landscape

The second landscape in Italy which delights me, is the Tuscan countryside south of Florence with its pastoral scenery and hilltop skylines punctuated with fortified towns including Assisi, Arezzo, Barga, Luca, San Gimignano, and Siena (Image 5, above). Contrary to the pleasure of taking a train in Northern Italy, having a car is almost a must to explore the hidden marvels of Tuscan medieval towns. Of course, like in the north, one finds many rural villas, but here, they are usually grand estates with a majestic palazzo accompanied by sumptuous formal gardens.

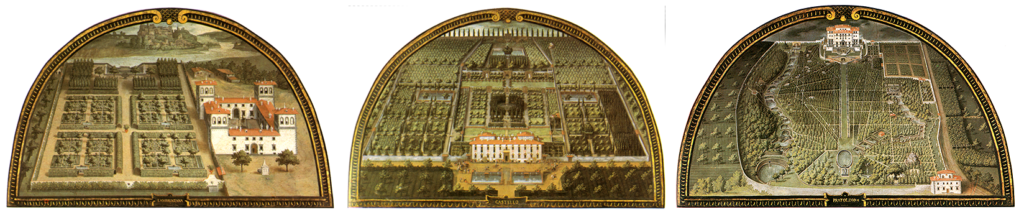

Many of the rural properties surrounding Florence (now part of UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites) were established between the fifteen and seventeenth centuries by members of the Medici family. Beyond the agricultural function associated within the landscape, the symbolic and aesthetic content reflected power and wealth, pleasure and leisure. Many of these villas are beautifully portrayed in the form of bird’s-eye perspectives by late sixteenth-century Flemish painter Giusto Utens. The 14 remaining half-moon forms—coined in French as lunette and typically located under a round-headed arch in a building—were painted between 1599 and 1602 and represent some of the most beautiful family estates of the Medici (Image 6 below).

These country seats are impressive and considered princely residences—with the exception of the urban Palazzo Pitti in the city of Florence. They are set within geometrically subdivided gardens offering panoramic terraces overlooking the valley surrounding Florence. The gardens are at times park-like and accommodate greenery formed by domesticated dwarf citrus trees, flower and herb beds, fountains, statues, and man-made folly grottos.

These paysages—landscapes named in French when represented in art—exhort man’s cultural imprint on almost anything they touched over the centuries. The ancestral plowing of the land, the political division of fiefdoms, and the establishment of Italian gardens are all part of what Vittorio Gregotti calls a principle of settlement.

Simone Martini

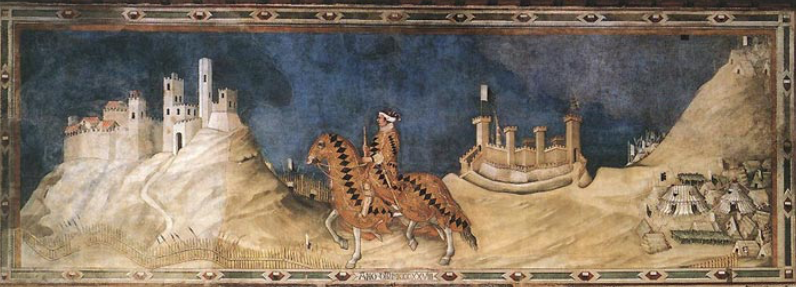

Since visiting Verona and Siena for the first time, I have come to love a style of painting called International Gothic, a movement that spans from the High Gothic to the advent of the Renaissance. It negotiates the transition between the depth of Gothic art and suggests the perspectival space central to the Renaissance. In particular, I have admired the Sienese School represented by artists such as Duccio, and the brothers Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, however my particular favorite is the artwork by Simone Martini (c. 1284-1344). Martini’s numerous frescos can be seen in the Palazzo Pubblico of Siena. The Guidoriccio da Fogliano among the countryside remains for me a marvel of painting (Image 7 above). Although, research in the 1970s re-attributed the work to a much later artist—whose name remains unknown to me—for me it still represents Simone Martini.

Guidoriccio da Fogliano

(Above image 8) My particular interest is the upper part of the overall composition which depicts the Condottiere Guidoriccio (Guido Riccio) da Fogliano riding his horse to survey his newly acquired territory; property that he won after overrunning “the fortress of Montemassi, which had become a hideout for Ghibelline outlaws…” The centrality of his presence within a theatrically orchestrated scene depicts him as regal, wearing sumptuous clothing that extends over his horse making him one with the animal; a strategy underscoring the symbiosis between the rider and animal as symbols of majesty, magic, and power.

Three principles of settlement

Principle 1: Montemassi as town

Beyond the depiction of military glory personified by the centrally positioned war captain da Fogliano, I am drawn to the fresco’s background with its three principles of settlements. To the left is the Tuscan hill town of Montemassi with its fortifications incorporating the houses in the old style. At its foot, is the symbol of a tenuous but continuous line of defense, offering an overall atmosphere of the town as one of decline and fragmentation—a reminder of “the universal truths about warfare, its destruction and its desolation.”

No suggestion—as would typically be the case in the depiction of cities and towns—of various monuments indicating religious, commercial or political stature. Only modest buildings lining the defensive walls with towers highlighting, perhaps like in Siena, the wealth of certain patrician families. Because the view of the town is frontal, we have no indication of the urban disposition of streets, public plazas, or gardens.

In the background of Montemassi, behind what seems to be a continuous concentric palisade, are signs of conquest represented by the victor’s black and white banners emblematic of the city of Siena.

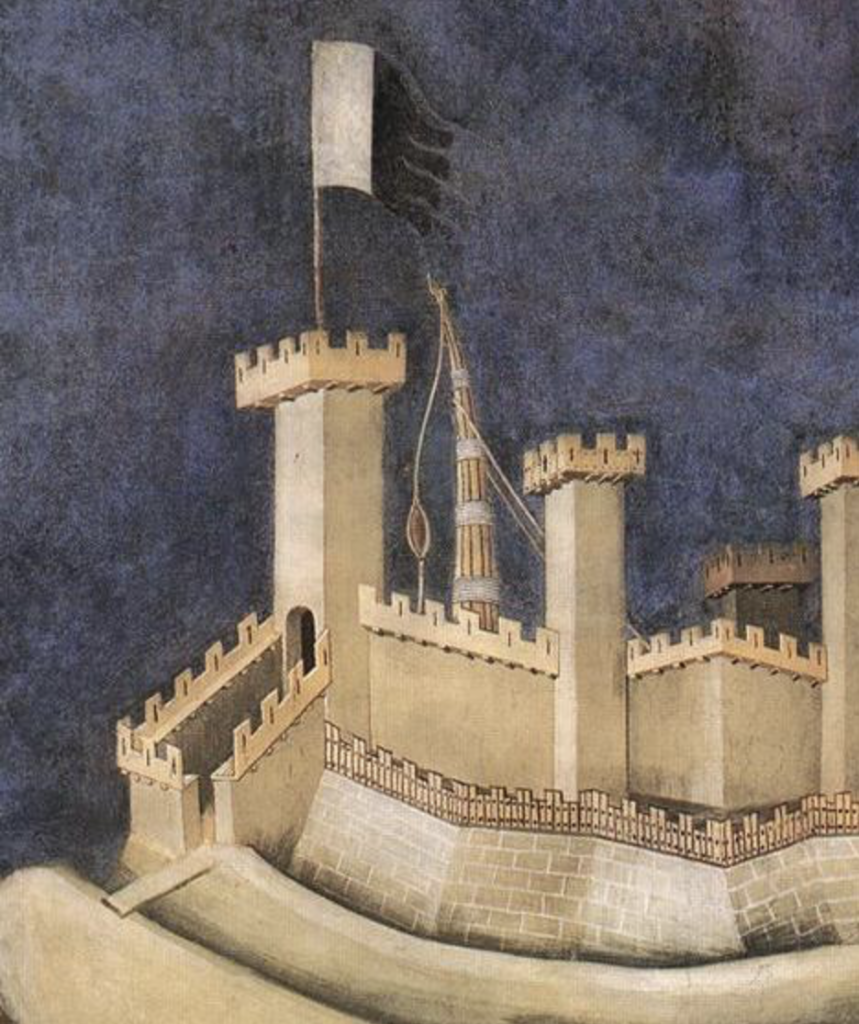

Principle 2: Battifolle as castle

To the right of Montemassi, “built [according to history] by the Sienese during the siege of [that city],” and situated farther in the background to the right of the war captain da Fogliano is the “bastita” of Battifolle. The austere and frontal composition of the castle is framed by four symmetrically positioned towers, symbolically underscoring the need to combat threats from the outside. A triple defense system is visible and formed by a traditional moat, followed by two diamond shaped “town-walls circuit” ramparts.

The high crenelated walls encircle the city along the four towers, while the second defense wall—suggestive of a later addition, is called a glacis—a new medieval fortification system formed by a sloped wall to counter escalades; and most importantly, to allow the ricochet of incoming projectiles off of the glacis and back to the attacking forces. An elaborate set of walls that shows a recognition of modern defense systems in contrast to medieval tactics, warfare, and weaponry, which is further illustrated to the left of the castle with a stone-throwing machine to defend the gate.

Finally, two entrances are situated on either side of the castle of Battifolle, which might seem strange given the vulnerability of openings. The towered gateways carry, respectively, the flags of Siena (to the left) and that of the family crest of Guidoriccio da Fogliano (to the right). Through the flag floating high above Montemassi both cities show their submission to the winner without the bloody description of a siege.

Principle 3: Nomadic settlement

The military camp at the far right of the fresco is located at the foot of a mountain. At its center are two tent-like pavilions; not impenetrable like Battifolle, but made out of fabric, while also securely anchored to the ground with three layers of tensioning devices. The distinguishing features of the two curved canopy-tents suggests that they serve as Guidoriccio da Fogliano’s living quarters with perhaps the smaller one reserved for meetings of military officers.

Surroundings these pavilions, the closely set identical triangle tents for the soldiers offer basic protection against rain and wind. They are covered with hay to form insulation to shelter the soldiers with rudimentary comfort. A miniature tree canopy suggests the only vegetation within the entire composition.

Visible behind and on top of the mountain, the camp seems to encircle the terrain, thus alluding to the size and power of the Sienese army. Flags offer a prominent point of identity in the camp, punctuated by soldiers’ spears pointed towards the sky as if ready for combat. The nomadic quality of the camp suggests a third principle of settlement. One that is mobile, temporary, and transitory.

Conclusion

I have always admired the delicacy of this particular fresco and how, with so few pictorial elements, Simone Martini was able to communicate a narrative of conquest and pride. The theatrical stage is set: a barren landscape with three types of settlements as background and support for the story, the unifying blue sky, and the sole actor center stage, all a powerful chronicle of the history of this place.

Cities and urban environments have often acted as background for the story telling of a painting. This fresco reminds me of the beautifully executed Teatro Olimpico (1580-95) in Vicenza, designed by Andrea Palladio (image 11 above). In it, three streets, created in perspective, are the background for the stage.

More recently, the unbuilt competition entry by Raimund Abraham for the Peggy Guggenheim museum (1985) achieved a similar scenographic purpose (Image 12 below). In it, he proposed a large classical amphitheater atop the incomplete Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, oriented to the Grand Canal where the performance relies on multiple unknown actors (the public) who come into play during the cycle of day and night.

Other blogs of interest on painting

Hubert Robert: Painting as a source of knowledge

Still lives by Ben Nicholson

Le Baron Tavernier: a cafe terrace in the middle of the Lavaux vineyards, Switzerland

Architectural Education: Robert Slutzky. Part 2

Edward Hopper