Door Locks in Corripo, Switzerland. North of the Ticinese city of Locarno, Switzerland, high up in the Verzasca valley, is a picturesque 13thcentury vernacular village called Corippo. It seems to be built at the end of the world (the first official access road was only constructed in 1883), and, while not much has changed over the past centuries, it is a must to visit. With only 12 inhabitants in 2018, it is the smallest municipality in Switzerland, however, it is better known for its use of stone. Throughout the village, paved granite paths, granite walls, granite stairs, and steep slate roofs create a visual harmony that is both striking and overwhelming.

Corripo

On the fall day of my visit, the atmosphere was eerie. I did not encounter any inhabitants and a mist of rain gave the village an even more mysterious quality. Carefully negotiating the narrow, crooked paths, I admired each dwelling for its simple and unassuming geometrical form. Each house stood proudly, defying the rugged terrain, with small window openings accentuated by bright white lime stucco.

The buildings revealed the inhabitants’ need to shield themselves from the severe winter climate. This authenticity was of intense beauty, and a testament to man’s know-how and to the ancestral alpine building traditions.

Vernacular and indigenous buildings

Throughout the world, the beauty of vernacular buildings is that they are designed by non-architects. Be it modest dwellings, public buildings, granaries or farm buildings, there is something authentic and spontaneous in an acquired knowledge that is nonacademic. The craftsmanship was handed down from father to son, and the skills were perfected from generation to generation.

Gestures of cutting, sanding, placing and adjusting materials — in this case stone on stone — is part of the long history of civilization. A desire to protect oneself from nature, to create a place called home, to secure possessions, and often to house under the same roof one’s livelihood (i.e. farm animals), remains part of humanity’s quest for survival.

Locks

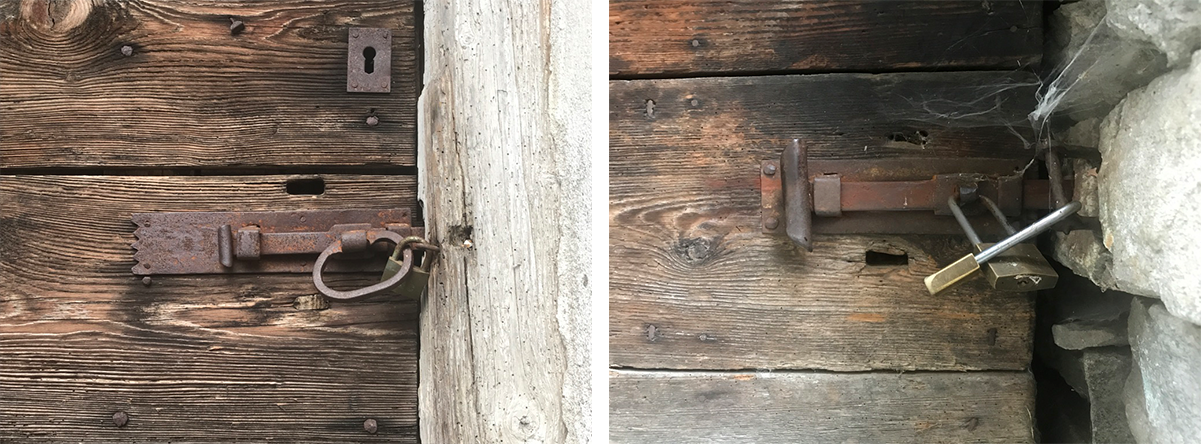

As familiarity with Corippo settled in, I became intrigued by various openings and, in particular, the entrance doors of each dwelling. Deeply recessed in the wall, and small in scale, they were the only tangible indication of human habitation in the village. Each of the doors had a latch. Upon closer examination, most of the hardware was similar, incorporating a handmade design featuring a simple forged slide bolt and a door latch mechanism.

Constructed from wrought iron, the form was either a long flattened thin rectangle or a cylinder with an elegant curved ending. Fastened with iron nails, the bolt mechanism included a door handle in the form of a stirrup scaled to the human hand usually delicately decorated. This design was commonly used in the 18th century, and confirmed when I found the date 1720 on one of the handles. The actual locking of the doors was done with an old-fashioned skeleton key or more often with a contemporary lock.

The scale of the dwellings, and the beauty and simplicity of the locks united, for me, the village through the down-to-earth practicality of design. When I returned home that evening, my visit reminded me of the importance of material culture. Architecture and its affiliated objects continue to reflect societal rituals, and this village at the end of the world was a testament to those values that I had learned early on in my architectural education.

For additional blogs on vernacular interventions

Casa Rezzonico by Livio Vacchini, Switzerland

Architectural Education: lessons from vernacular architecture-inventing versus re-inventing

Architectural Education: A question of preservation

Street pavement as an urban landscape: Wittenberg, Germany