First steps in a student’s design process. As I matured as an architecture student, I didn’t lack ideas in response to design studio prompts. Ideas seemed to come naturally to me and were triggered by the process in which I was trained to think of a thesis, a program, or a BIG idea (owning a theoretical position on the act of projecting). I believed my métier was in making architecture through the act of building, especially that in Switzerland a culture of construction is integral to design. Most often, this process used functional requirements and explored my interest in an organization of spatial narratives. Retrospectively, this attitude was predictably based in relationships to human occupations (functions).

First steps in a student’s design process. As I matured as an architecture student, I didn’t lack ideas in response to design studio prompts. Ideas seemed to come naturally to me and were triggered by the process in which I was trained to think of a thesis, a program, or a BIG idea (owning a theoretical position on the act of projecting). I believed my métier was in making architecture through the act of building, especially that in Switzerland a culture of construction is integral to design. Most often, this process used functional requirements and explored my interest in an organization of spatial narratives. Retrospectively, this attitude was predictably based in relationships to human occupations (functions).

Another approach in vogue during the postmodern era of my studies was the “quotation of shapes” for the sole visual pleasure of the plan—at least for students. For me, this method never addressed issues of primary importance. I trusted at that time my unsophisticated instinct was that forms should express a quality in design thinking—aesthetic, poetic, cultural, social, structural, site or territorial conditions, to name a few.

A question of process

I will admit that this methodology may seem banal or even mundane given today’s increasing desire for students to develop concepts that are far removed from what I call common sense. Often, at least in a student’s early years, the urgency to stand out by seeking the unusual as a pretext to develop a project, seems natural—often de rigueur and sadly endorsed as a basis for judging creativity. Be it for reasons of fashion or an obsession with novelty, rarely do students explore what the Shakers called the nature of being; a desire to fulfill the artifact’s own vocation leading to a timeless statement.

Do not misread me. I endorse creativity as an act of re-invention (and not invention), favoring ideas and concepts that remain simple: not for an aesthetic or a minimalist attitude, but for the purpose of editing one’s thought process until the essence of the project is expressed and owned with confidence. However, I always remind myself and others that the search for simple ideas should never lack complexity and sophistication in their spatial resolution. For my students it seems like a broken record when I say that a project should be simple rather than simplistic, complex rather than complicated.

Of course, the how and the why I became confident in moving a project from idea to execution was not so simple. I had to learn the meaning of process and apprentice it through various iterations in order to move my projects forward. While the acquisition of a set of skills had much to do with my becoming a resourceful aspiring architect, it took time to develop a process by which I could build a solid project. Not that I was looking for a universal method that would guaranty a successful result, rather I sought a way to objectively test ideas and concepts all the while progressing and refining the overall design.

The first steps of a design process

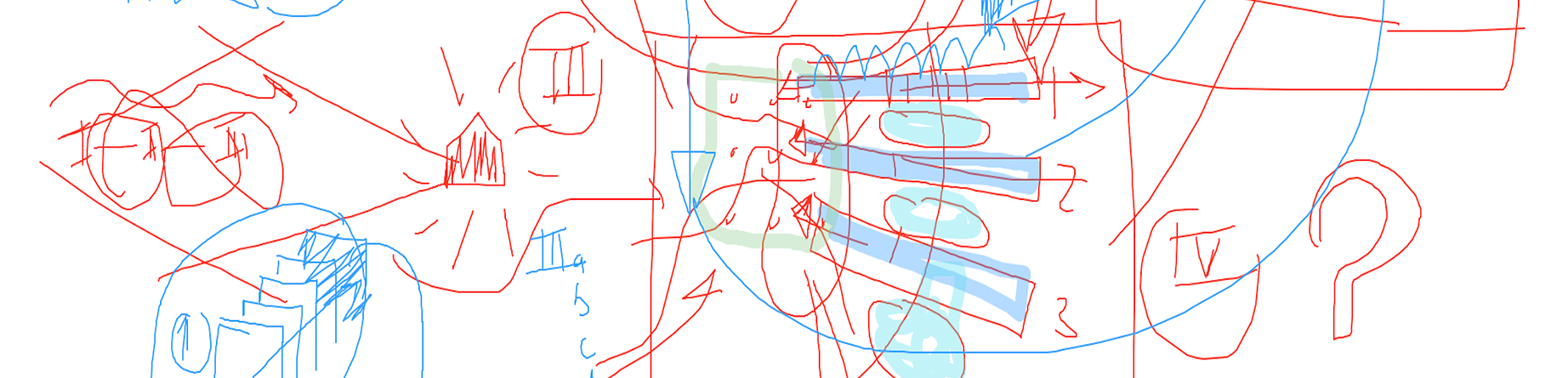

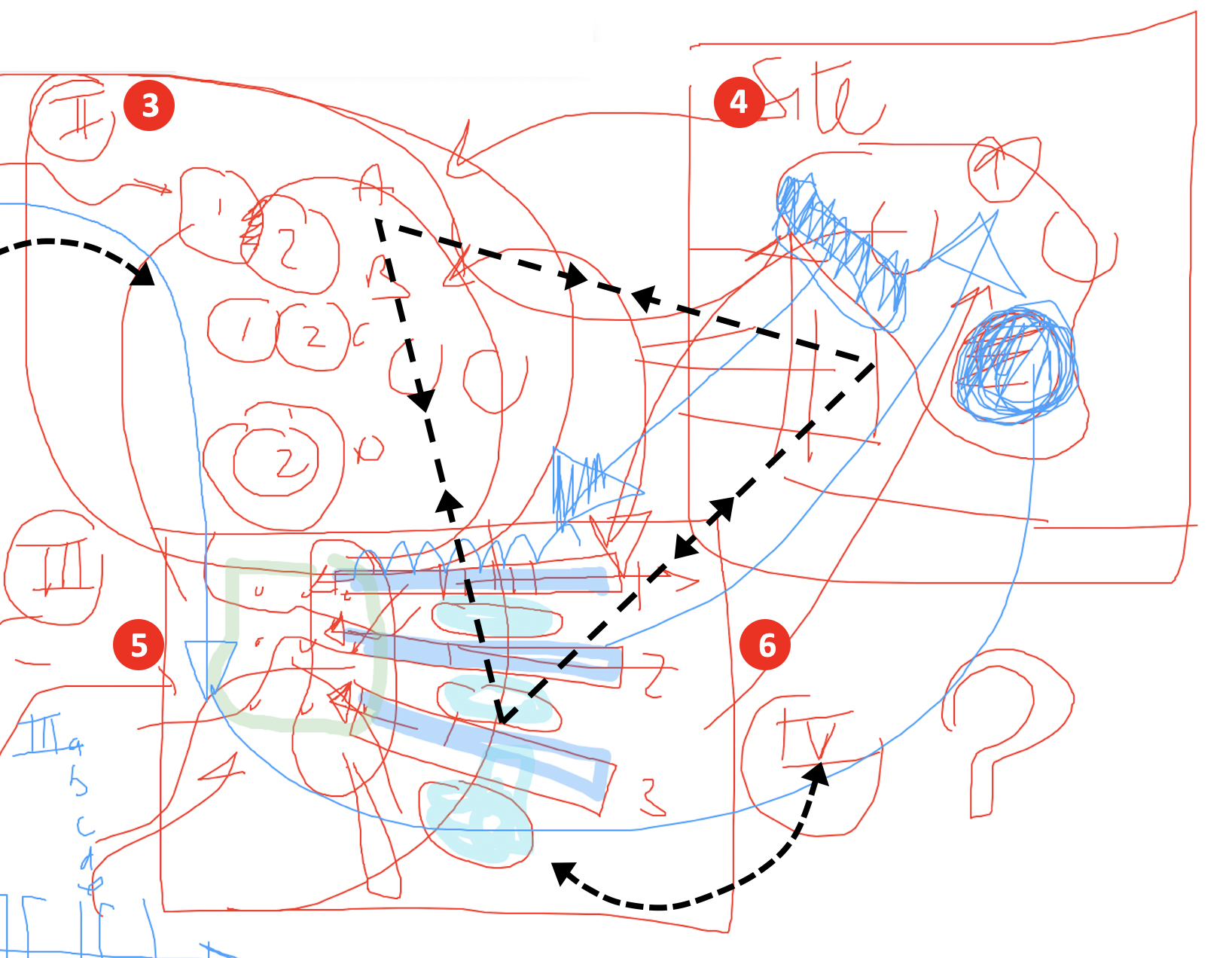

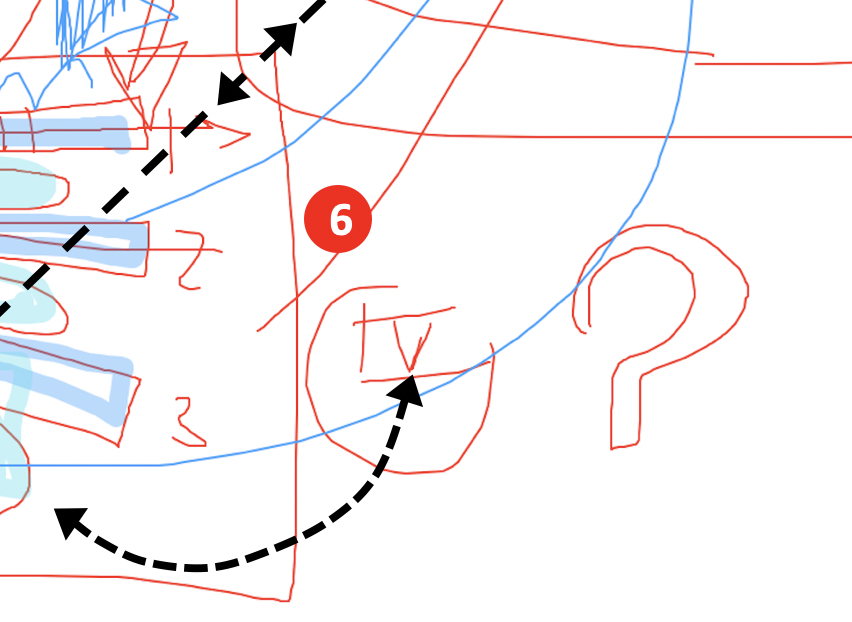

Image 1: suggested chronology of one of many design processes (author’s diagram)

Image 1: suggested chronology of one of many design processes (author’s diagram)

Teaching second year students is an opportunity to focus on developing good work habits by emphasizing process as an important design skill. At this early stage in their studies, too often the design project takes center stage, and unless they learn a process, many students may excel in the deliverable of their project but fail in retracing the circumvented steps that brought them to that success. Without knowing the why and the how, when encountering different struggles as projects become more sophisticated in scope, students may feel at a loss when assessing tricky design situations, what they often share with their instructors as: “I have a problem, I do not know what to do.”

The other day, when reflecting upon a recent discussion with a group of thesis students, I charted out a generic process summarizing a set of steps they had encountered in designing their thesis (Image 1 above). I decided to share it with my second-year students, and, later that afternoon, retraced the diagram with them, emphasizing key moments in the design process.

All of this was accompanied by words of wisdom to caution students that process is rarely a linear action without hurdles.

I believe that in the early stage of becoming an architect, being exposed to a typical process offers opportunities to set students on a healthy footing to improve their design skills. The following comments summarize my discussions with my thesis students—and subsequent presentation to my second-year students—and highlight key steps which are malleable based on the nature of the project.

Thesis and functions

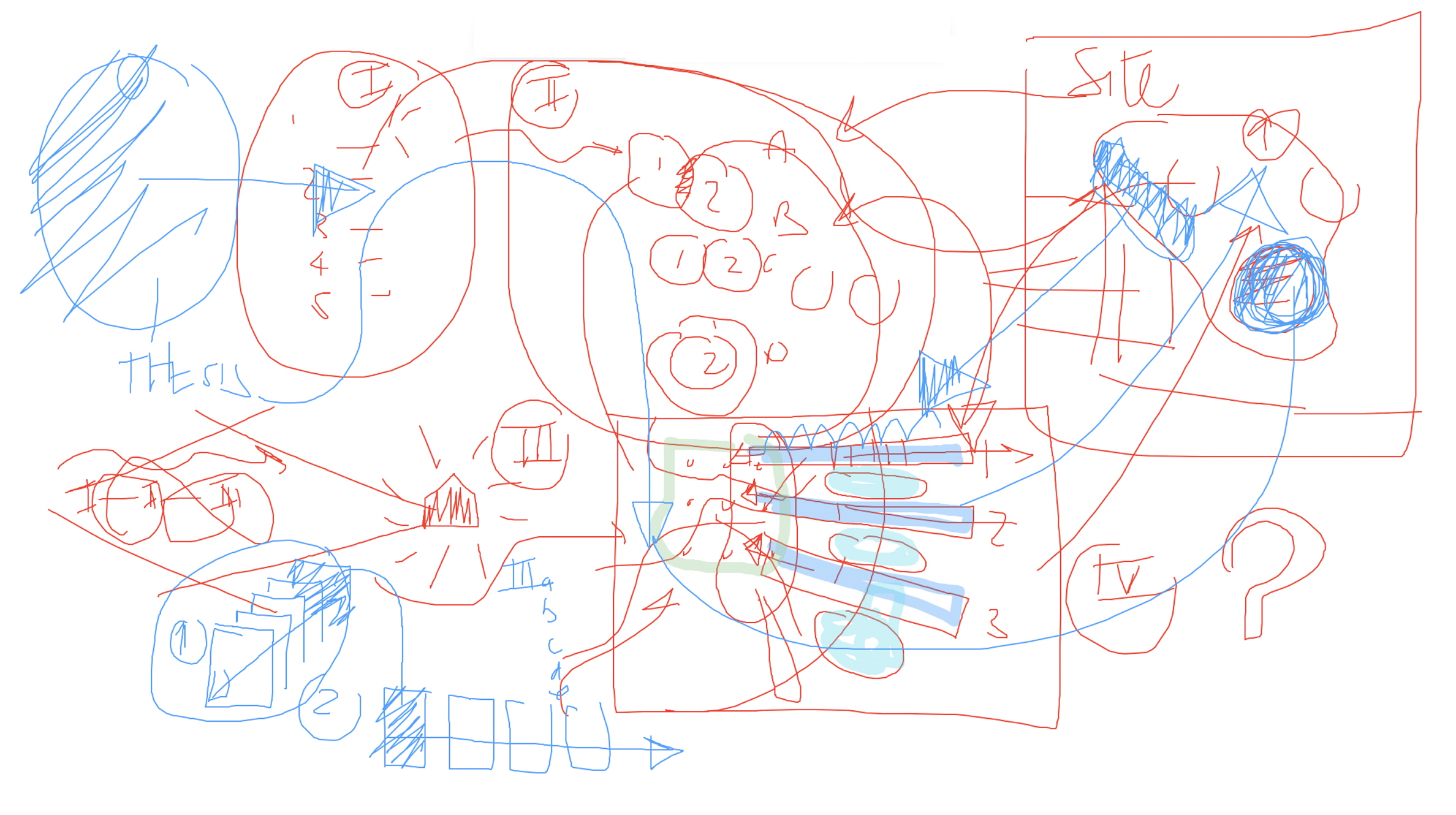

Image 2: relationship between thesis and function (author’s diagram)

*Note that all highlighted numbers correspond to the red dots in the featured diagrams.

Thesis student typically start their design by establishing an idea, which is often in the form of an argument or a program that is the basis of their senior design project (Image 2, number 1, above). Thesis ideas can be about architecture (i.e., interest in light as procession), promote a social agenda (create a library for the homeless), or provide a critique (questioning the purpose of the iconic suburban house in the 21st century) to name but a few topics that I have encountered in my teaching.

However, for a thesis to be an architecture thesis—which is fundamentally different—it cannot simply be stated as an idea or a set of ideas; it needs to form an argument that is worth discussing architectonically in the search for a spatial coherence. For me, this remains the primacy of any architecture thesis at an undergraduate level.

The scope of the project must be tested early-on in terms of the fitness and strength of the argument in order to generate questions that should be endless. (Image 2, number 2, above) At this stage of the research, if the inquiry seems infinite, I believe that this is a good sign as the thesis topic shows depth and promise for robust developments that can balance intellectual and pragmatic concerns.

Often, in this assessment phase, either a set of functions are superimposed on the thesis, or are generated from the thesis itself. It is here that an important conceptual dialogue takes place between thesis and programmatic functions, and, in the best of worlds, results in a back and forth transaction where concession and invention take place. Again, this phase is critical as it fleshes out the depth of the inquiry necessary to develop a yearlong thesis.

As a side note, for second-year students, typically a set of functions are included in the design studio brief, thus the above process (idea (1) to function (2)) may be reversed (function to idea).

Functions and their first conceptualization

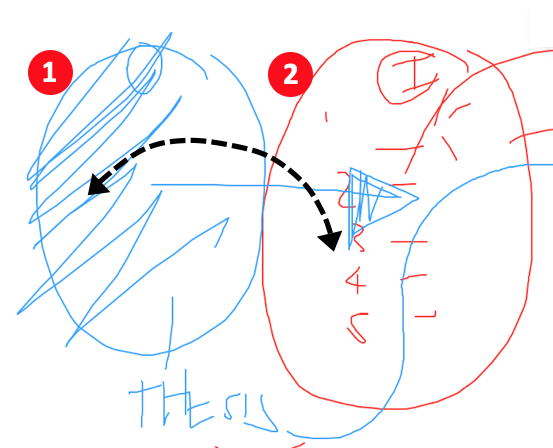

Image 3: relationship between function and iteration (author’s diagram)

Image 3: relationship between function and iteration (author’s diagram)

In a third phase, the testing of ideas is furthered by diagraming possible relationships between functions and ideas by first sketching out initial preconceptions. (Image 3, number 3, above) I believe this is an important strategy, because as designer’s we always carry spatial bias that we have inherited and forwarded from project to project, thus the need to set those ideas on paper in order to question their validity at this precise moment in the design process.

More importantly, this cleansing of predetermined and often unchallenged notions about what constitutes space should be accompanied by establishing unforeseen and desirable connections between functions, and, without ever losing the original premise, seek relationships between functions and thesis ideas. This allows a first set of spatial iterations to be visualized and should remain expressed at a conceptual level to ensure the integrity of the process between stages 1 and 3.

In diagram 3, sketches as part of a design thinking process are drawn as bubble diagrams, often called Venn diagrams. In this example, the iterative process depicts relationships between functions by highlighting their attributes through spatial proximities. In a typical French fashion, I enjoy classifying, ordering, and systematizing ideas as I move to discover a network between them. At this point, there is no hierarchy expressed in the sketches, simply an endless discovery of possible spatial permutations.

This iterative process is absolutely essential for any development of ideas and was thus applicable to the discussions with my second-year students.

Site and formalization

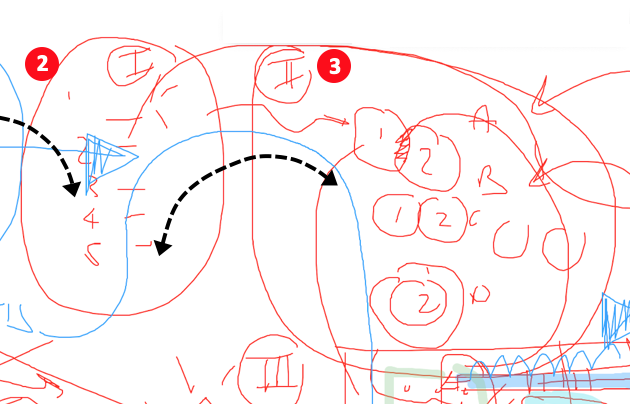

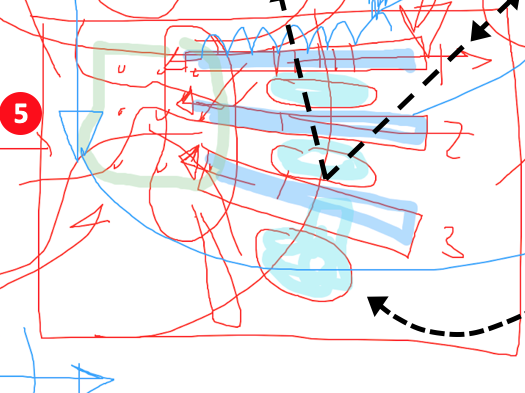

Image 4: trilogy between functional iteration (3), site (4) and first tectonic visualization (5) (author’s diagram)

Image 4: trilogy between functional iteration (3), site (4) and first tectonic visualization (5) (author’s diagram)

At this stage of the thesis, regardless of the level of a student’s academic year, multi-tasking becomes key in developing a thought process between formalizing an architecture strategy (image 4, number 5) as a translation of functional relationships (image 4, number 4) and the incorporation of a context through site strategy.

Site—an unfortunate intermezzo

I know, site conditions and a principal of settlement ought to have come earlier in a student’s deliberation, but with a typical thesis—at least as currently conducted in my school and by those that I mentor—the identification of a site is seen as a pretext, a locus to unfold the thesis and not a generator of ideas and spaces.

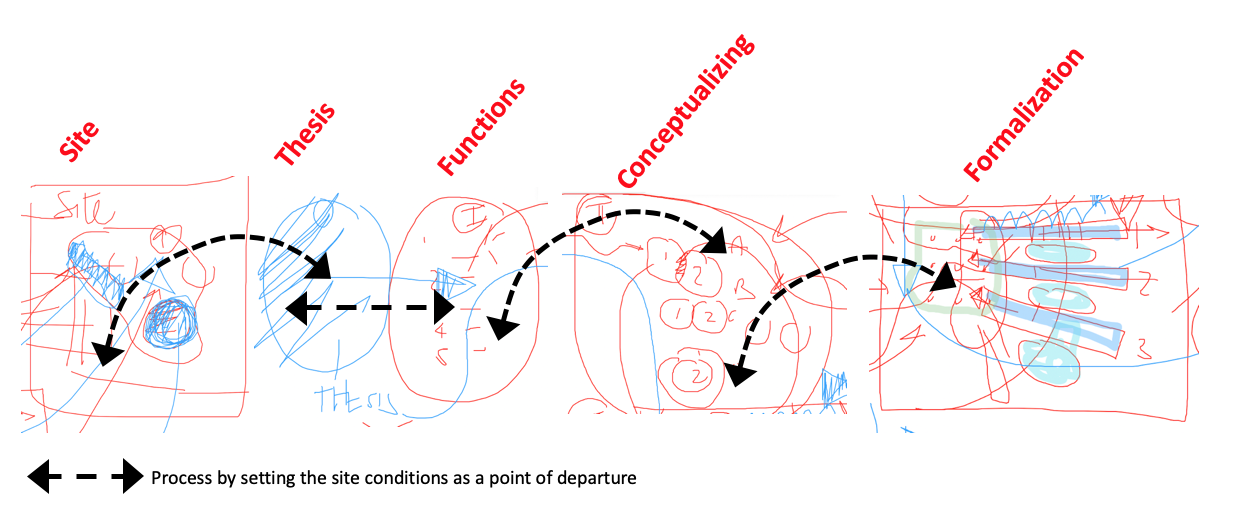

As architects, and in particular among students in second year, a site is proposed as the place where the project develops at the intersection of history, context, and geography. Thus, the diagram (image 4) can be easily manipulated to relocate the site’s preoccupation (image 4, number 4) to an early stage in the design process; perhaps even as a point of departure in the formulation of an idea.

In my discussions with my second-year students, I emphasize site conditions as a potential trigger of ideas prior to formalizing Venn diagrams. Again, all of this demonstrates the need for a designer’s versatility in interpreting a typical design process. The process is a guide to reference when evaluation progress or overcoming a perceived stumbling block. The adjusted process diagram reflects those alternatives (Image 5 below). Image 5: resequencing of the design process by emphasizing SITE as the generator of the thesis (author’s diagram)

Image 5: resequencing of the design process by emphasizing SITE as the generator of the thesis (author’s diagram)

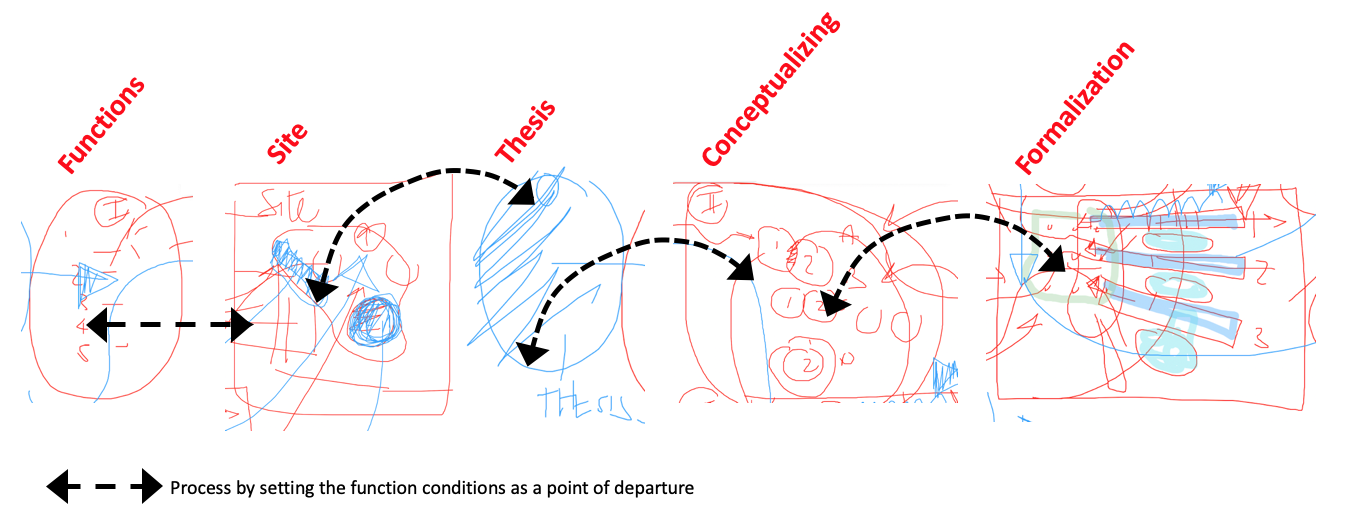

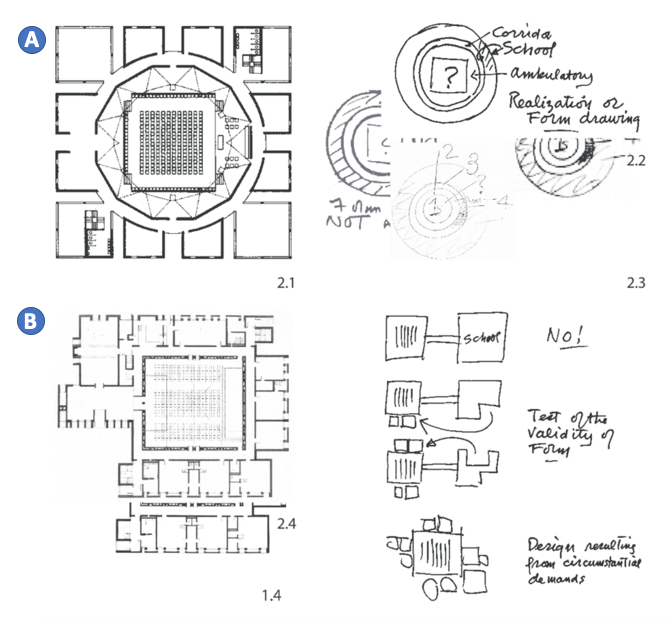

Once again, the overall sequencing of the original diagram (Image 1) was in response to the process defined by my thesis students, and while it shows inherent flaws pertaining to the thesis process, diagraming their progression was beneficial for them to highlight other methods of investigation. This strategy offered the students ways to rethink the innate hierarchical order they had established, and hopefully invited them to constantly reflect on the validity on their process. Image 6: resequencing of the design process by emphasizing FUNCTION as the generator of the project (author’s diagram)

Image 6: resequencing of the design process by emphasizing FUNCTION as the generator of the project (author’s diagram)

To take this flexibility of ‘a process’ further, one might have a client with stringent functional requirements, from the types of room to the amount of closet space and library shelves. thereafter, imagine the client says, help me find a site! Image 6 (above) illustrates a revised process.

Note. For La Petite Maison for his mother, Le Corbusier developed a plan AND then searched for a site. “I boarded the Paris-Milan express several times, or the Orient Express. In my pocket was the plan of a house. A plan without a site? The plan of a house in search of a plot of ground? Yes!”

Architecture strategy

Image 7: first tectonic visualization (author’s diagram)

Images 7 and 4 were seen as first attempts to conceptualize the Venn diagram in tectonic form; moving from the realm of ideas to those of form and space. In the above example (image 7), platonic forms give shape to the architecture by developing spatial conditions through various shapes and sizes and, most importantly, possible spatial relationships between each of the forms.

An order emerges through the three long bars (a habitat for bees in this specific sketch taken from student’s thesis) enabling additional spaces to nestle between them (research centers in oval), which are all oriented towards the green square (market place). Note that the parenthesis indicates the student’s functions.

While these rough shapes remain suggestive of certain tectonics, the ability to retain their shapes at a conceptual level prevents the design from being locked into a definite formal organization.

Testing of one’s ideas

Image 8: testing the validity of one’s concept (author’s diagram)

Image 8: testing the validity of one’s concept (author’s diagram)

Previously I advocated a need to see shapes as suggestive and not simply as a means of defining the overall form of the building. This sixth phase becomes a milestone in the overall process. Now that the thesis, functions, and numerous relationships have given birth to the first formal iteration (i.e., model of life, principal of settlement, functional interpretation, structure as space defining), it is imperative that all of the above ideas get tested, thus the symbol of a question mark in Image 8. Image 9: testing the validity of one’s concept (author’s diagram)

Image 9: testing the validity of one’s concept (author’s diagram)

This phase (number 6) is a logical extension of the previous developments, and represents a moment of introspection and a conversation between the designer’s intentions and the power of suggestion offered by the drawings (Image 7, number 5). In the professional realm we might call this a pre-design phase that is accompanied by the need to evaluate the project; an insight that confirms either a solid direction leading towards a high-quality design, or the urgent need to revisit some fundamental assumptions and return to the “drafting board” to clarify the overall intentions.

This phase of testing, interrogating, and reassembling can be discussed at length within a professional or academic setting, but the end result is that a project always gains new meaning here. Thus, I have represented this phase with green arrows in Image 9; arrows that are suggestive of a back and forth. Also, in this illustration, I use the revised process diagram which sets the site conditions as point of departure for the thesis.

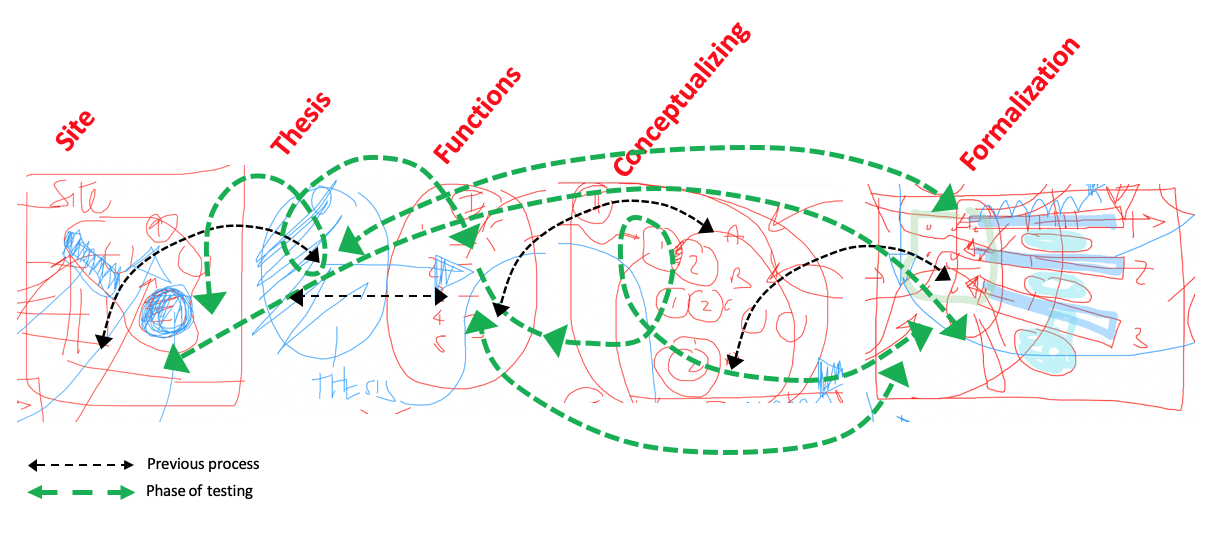

Image 10: Google -two designs for the Unitarian Church in Rochester, NY by Louis I. Kahn

Image 10: Google -two designs for the Unitarian Church in Rochester, NY by Louis I. Kahn

As a side note regarding the testing of ideas, I always wondered how American architect Louis I. Kahn found the courage and empathy to question a beautifully organized plan designed with Beaux-Arts principles (Image 10, A), to then set in motion the need to make substantial changes in order for a new design to emerge (image 10, B), which Kahn writes as “Test of the validity of Form,” and “Design resulting from circumstantial demands.” Image 10 illustrates the genius of Kahn’s ability to recognize the need for what I would call a revolution in the organization of the plan, one which eventually was built and became part of his oeuvre.

Linearity of a process

Image 11: Questioning the linearity of a process (author’s diagram)

Image 11: Questioning the linearity of a process (author’s diagram)

Returning to the discussions with my thesis students, too often, in these formative years, process suggests a linear evolution that moves seamlessly from one stage to the other. This is expressed in the diagram above (Image 11, number 7), and while one may wish that a process is continuous nothing could be further from the truth, especially at this stage of the project.

Iterative process

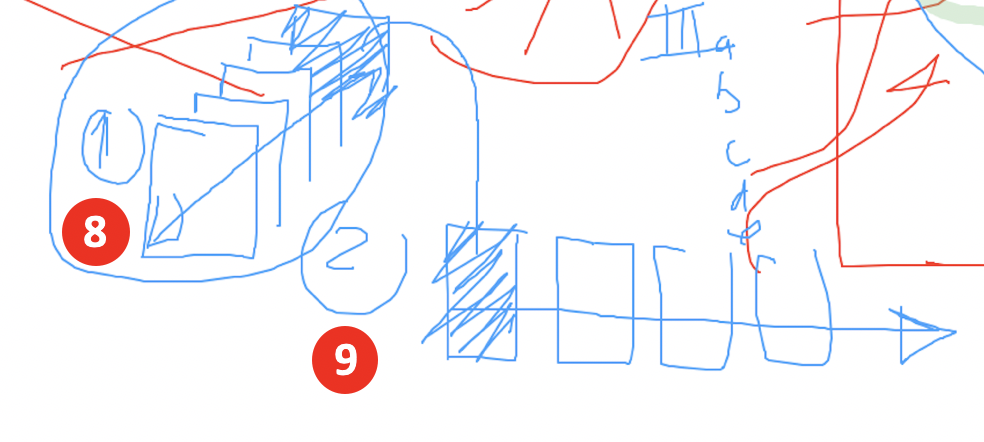

Image 12: Two iterative processes

Image 12: Two iterative processes

In a previous blog, I addressed two manners through which an iterative process could move a project forward, either by working ideas out through superimposing sketch over sketch (Image 12, number 8), or by diagraming concepts one next to the other (Image 12, number 9). It is important to note, that the two strategies are not mutually exclusive and do not take a hierarchical role in the design process.

In conclusion, the necessity to ground students with a process is a first attempt to let them objectively analyze their design journey. Yet, as discussed above, it is obvious that there are endless permutations regarding process. Design maturity, and most importantly any design process relies on the initial thesis that a student set forth to argue during in their project.

Architectural Education: Some thoughts on thesis

Architectural Education: Some thoughts on teaching. Part 1

Architecture Education: The nature of IDEAS