After investigating the historical origins of the Speicherstadt (blog) and its use of the neo-Gothic style I delved into how they functioned with an eye toward the future.

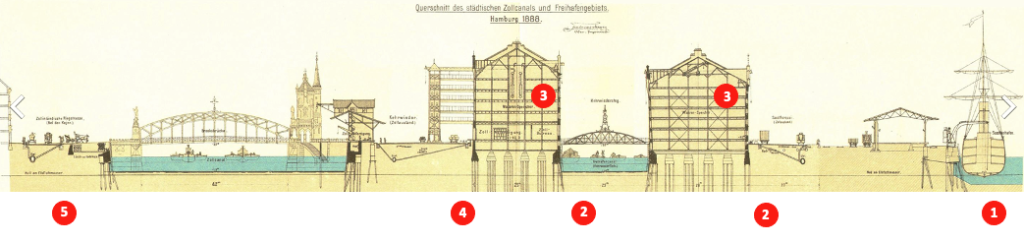

The simplicity of the work around and within the warehouses can be described as two important activities. Note that numbers mentioned in the below paragraphs correspond to those highlighted in red in image 14 above.

How the warehouses functioned

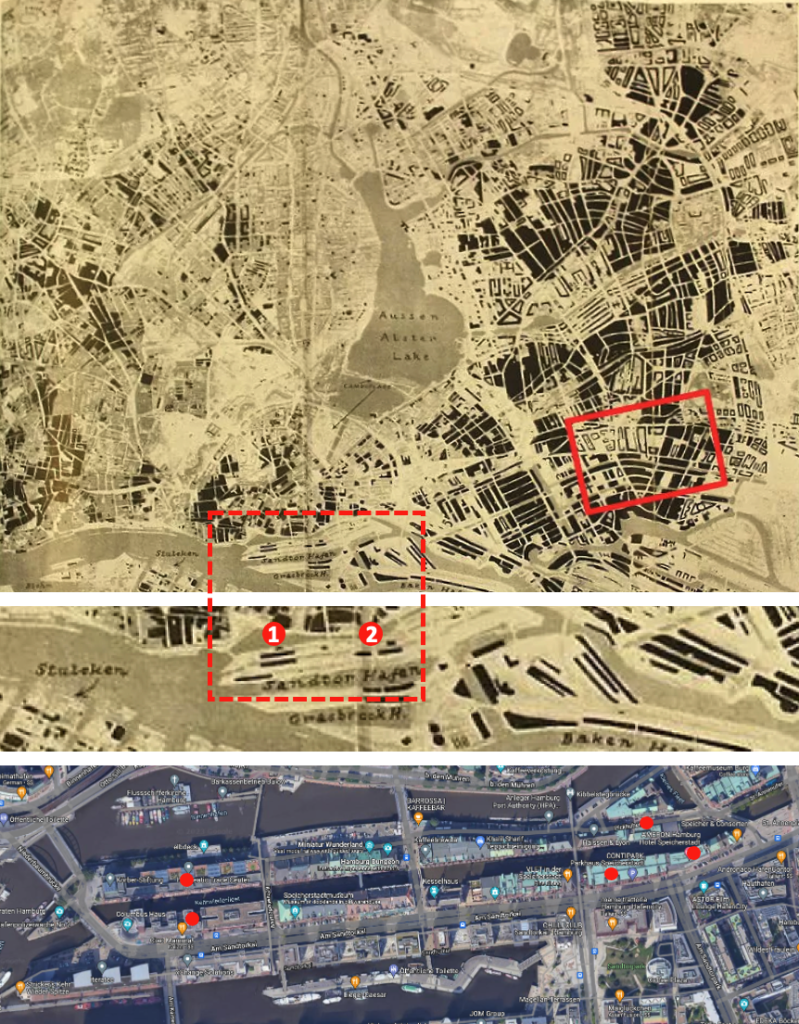

- After goods arrived in the port of Hamburg by a seagoing vessel (1), they would be unloaded on the quays and either brought directly to one of the adjacent warehouses (2), or loaded onto a barge (Schuten in German) or a low boat to be transported by canal to a different specific warehouse (2). These wooden barges had no masts, sails, or engines, thus enabling them to navigate under the numerous bridges with only the manpower of professional Ewerführer (yawlers named after the boat type Ewers, which were used around the Elbe River). To protect the transported goods at night from theft, as well to safeguard the duty-free status of all products, most yawlers lived on their barges for several weeks prior to returning to their families on land for a short time.

- After being off loaded from the barges, the sacks, crates, barrels or bales were transferred through the floor hatches to designated floors in the warehouses (3)—floors that often were designed with various heights and weight capacities to accommodate goods as diverse as coffee, tea, cocoa, dried fruits and Brazilian nuts, exotic spices, carpets, wine, rubber, paper, metals or hides. Rope winches under the oriels allowed the goods to be hauled directly from the barges, while the boats were hooked to rings found in the brick foundations—above the oak pilons. Notice the three levels to hook your boat that provided anchor depending on the tide height (Image 16, above).

Stored goods were safeguarded by the Quartiersleute (warehousemen who always worked in teams of four, thus the term quartier, meaning quarter) until the cargo needed further transportation to the client. In addition to the skilled and efficient warehousemen who received, controlled, and assessed the condition of the goods—meaning how to “store, weigh, sort, clean, dry and ventilate” them appropriately, the thickness of the exterior brick walls offered obvious protection against temperature fluctuation, which was important for perishable goods. - As goods left the warehouses, they mostly found their way through wide dock spaces (4) where vehicular and rail transportation took place. Crossing the bridges over the custom’s canal to the city (5), was both symbolic and functional. Bridges functioned as the umbilical cord marking the connection between the closed quarter of the warehouse buildings of the Free Port Area (Speicherstadt), and the inner city of Hamburg, which was part of the larger German customs territory (Image 17, below). Of course, if goods needed to be loaded back onto vessels, the process would unfold in reverse.

- As an aside, on the quay side facing the city (4) I discovered numerous sculptures highlighting the warehouse entrances, symbols of the craftsmen who built these structures (Image 18).

Today’s Speicherstadt

During my walks throughout the Speicherstadt, I encountered numerous contemporary infills, notably the above mentioned hotel Ameron and the adjacent office structures. Many of these sites were left empty after WWII as Hamburg was heavily bombed by raids by allied forces over eight days in 1943. Hamburg was an important target as it was a large city with a robust industrial armament center, oil refineries, docklands and shipyards, and two U-boat pens supporting the German war effort.

The code name for the bombing of Hamburg was Operation Gomorrah, and reflected the British and American intention to create biblical destruction on the city through incendiary area bombing. At that time in the war, it was understood by the allies that to target civilian populations and their places of living also destroyed the “morale of the enemy civil population – in particular the industrial workers.”

Conclusion

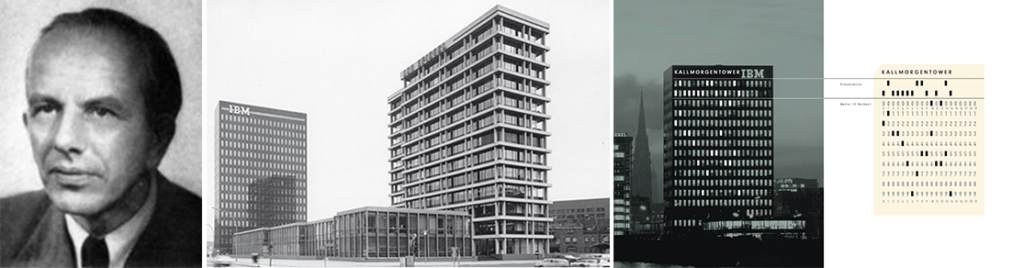

Early reconstruction and conservation of the Speicherstadt owes much to Hamburg’s architect Werner Kallmorgen. While practicing as a passionate modernist throughout his career—creating an architecture influenced by the work of Bauhaus director Mies van der Rohe in the United States—Kallmorgen’s legacy spans between his “cityscape-defining building ensemble on Spiegel Island [created with the rubble of WWII],” and the 19th century identity of the Speicherstadt. For some architects, and perhaps most architecture students, this aesthetic dialectic between modern and old might be at odds.

But as a European, I feel that this double operative viewpoint on formal issues embodies the complexity of an architect’s work operating in a city context. To maintain a “Zeitgeist” in one’s métier, while protecting—in our case the city’s historical lineage of the Speicherstadt—enables both the past and present to naturally coexist as an evolutionary testimony for the survival and sustainability of historic cities.

Certainly, if the bulk of the reconstruction of the Speicherstadt unfolded primarily between 1946-1967, further research might well confirm that Kallmorgen’s interest in urban artifacts—monuments and symbolic spaces that are part of the collective memory that give structure to a city—may owe much to Aldo Rossi’s 1966 book The Architecture of the City. And this despite that the book’s first translation in German appeared almost a decade later in 1974.

As a side note, I find it interesting that many architects that I admire seek out a lineage to shoulder their vision. Le Corbusier emulated Greek and Mediterranean architecture, Louis I. Kahn revered Roman architecture, and Mies van der Rohe looked to Gothic architecture to create his monumental buildings. Kallmorgen is mostly recognized for the design of the IBM building in Hamburg, whose façades metaphorically echoed the Hollerith Lochkarten (Hollerith punch cards) that were so ubiquitous for the running of IBM computers prior to the introduction of Mac software. Recognizing this analogy between punch cards and IBM’s façade is important, but perhaps too easy. I would suggest another historical argument that lies between the Speicherstadt’s rigorous neo-Gothic facades and its modern glass skyscraper interpretation, especially in light of Kallmorgen’s admiration of Mies’ architecture and design inspirations (Image 22 above).

Today, many of the contemporary interventions throughout the Speicherstadt that occupy the previously bombed out lots maintain the tradition of red-brick façades, yet, all of them express a renewed interest in a strict geometrical character that is both amicable to the warehouses Hanseatic Brick Gothic Architecture style and a need for a contemporary expression of an industrial monumentality.

In light of the above success of an interpretative maritime heritage, both for the original Speicherstadt and its contemporary interventions, the following question should be asked: Can the promotion of an exclusive cutting-edge standpoint—one that seems so much engrained in current American architecture teaching—maintain its stand as a leitmotif for an educational pedagogy? To simply promote a vision that is so extraordinarily different than the past one inherits no longer has a place in today’s complex world. Contemporaneity and progress can only take a meaning as one compares and contrasts the new with the old.

My visits to the Speicherstadt reminded me of a quote by Montesquieu: “The distinguishing feature of great beauty is that first it should surprise to an indifferent degree, which, continuing and then augmenting, is finally changed to wonder and admiration.”

I was aware of the Speicherstadt’s significance, but prior to visiting did not fully grasp how solving straightforward problems created an area with such functional and aesthetic architecture. Its overall elegance and beauty results from a balance between basic functional requirements, stylistic choices, use of materials, constructive principles, and decorative expressions. This allowed the Speicherstadt to speak of the nature of being, all the while interpreting aesthetic references.

As a professor of architecture, I try to remind students that the humble strategy of reinventing may be the most powerful act in offering a meaningful contribution to one’s art. For our discipline and métier—most important in its social responsibilities—to regain its letters of credential, it seems timely to question our teaching of Architecture (with a capital A), to the exclusion of that which is practiced with confidence under what I call architecture (with a lower a). Here, I include the Speicherstadt as lower a.

Postscript 1

In a past blog discussing modernism as an incomplete project, I wrote that:

When I was a student, we were taught to look at precedence in an informed manner and, in particular, contribute to a reading of a site through its cultural context. I remember one day being asked the question: “and what next?” I hesitated then, hoping I had understood the question, reiterated how I had come to the proposed solution that I believed was inventive, yet mindful of the historical implications.

With a complicit smile, my professor clarified his question by confirming my informed instinct, while asking what did I think future architects would make of my interpretation when viewing my project, my built project. If any form of continuity was to exist, I had to realize that something would come after my project, perhaps after a thorough analysis of my interpretative moves visible in the work.

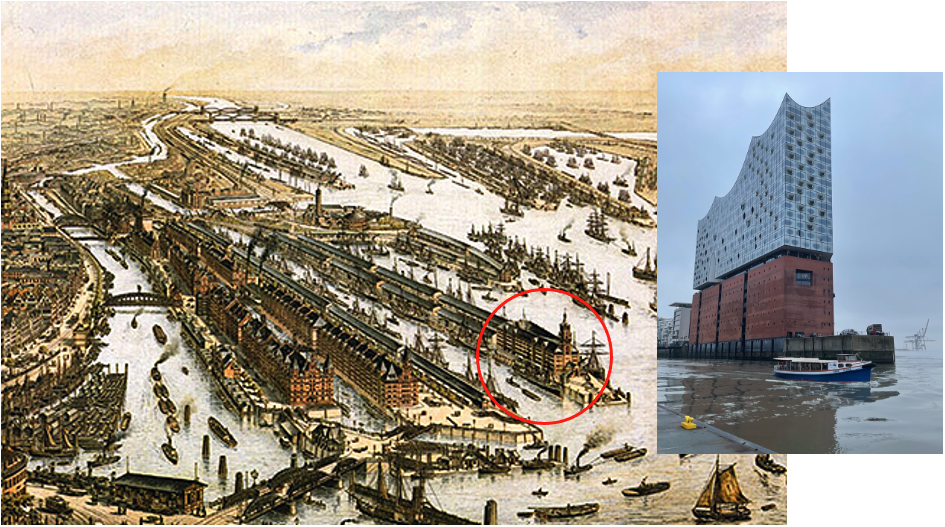

After researching the Speicherstadt and my visit to Herzog et de Meuron’s Elbphilharmonie (2001-2016), I discovered that the base of the philharmonic was designed by Werner Kallmorgen. After a fire at the Kaiserspeicher A in 1892 (not in the Speicherstadt complex), its reconstruction, and partial destruction during WWII, it was rebuilt on the same site between 1963-1966 according to Kallmorgen’s original design, featuring a brick façade that echoes “the vocabulary of the city’s historical façades: their windows, foundations, gables and various decorative elements are all in keeping with the architectural style of the time,” with modern improvements including semi gantry cranes that allowed cargo to be moved from ships directly to the quay. (Image 23 above).

With the creation of the Elbphilharmonie and a number of imposed design restrictions, “[t]he new glassy construction resembles a hoisted sail, water wave, iceberg or quartz crystal resting on top of an old brick warehouse;” there is now a tension between maritime and urban architecture. I love ideas that celebrate continuity that build on a past, yet redefine anew a vision for an existing structure. In this context, it might be time for academia to embrace the idea that a new generation of architects will focus more on issues of adaptive use in all of its contemporary iterations, rather than simply promoting an idea of the new.

Postscript 2

Prior to my trip to Hamburg, I fortuitously discovered a work of art in a nearby antique shop. The scene seemed familiar (perhaps a Hanseatic city) and the price worth my investment. Lo and behold, this woodcut was by German expressionist artist Klaus Wrager (1891-1984), and is part of the “Hamburger Holzschnitte” (Hamburg woodcuts) of 1935, describing the inner historic city of Hamburg.

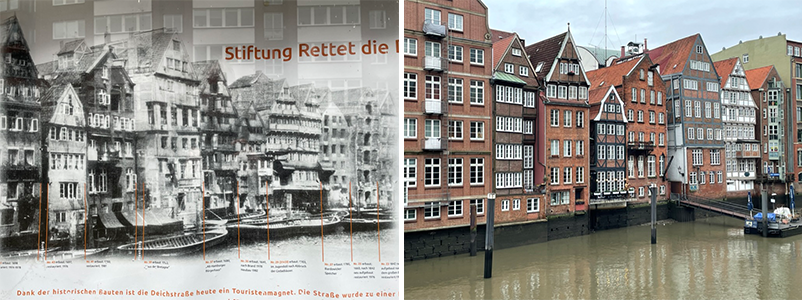

During my recent visit to Hamburg, I discovered the view from which Wrage took inspiration, namely the view from the Holzbrücke towards the half-timbered houses on the Deichstrasse facing the Nikolaifleet. To the right of the group of houses he features is where the great fire of Hamburg started in 1842.

Other blogs of interest

Speicherstadt in Hamburg. Part 1

Street pavement: Wittenberg, Germany

Architectural Education: A question of preservation

Casa Rezzonico by Livio Vacchini, Switzerland

Lessons from vernacular architecture—inventing versus re-inventing