“The distinguishing feature of great beauty is that first it should surprise to an indifferent degree, which, continuing and then augmenting, is finally changed to wonder and admiration.”

Montesquieu

Speicherstadt in Hamburg. Part 1. For reasons that I have yet to rationally pin down, I have, during my numerous travels to Germany, ignored the city of Hamburg. Other cities, such as Berlin and Leipzig (where my father had lived and studied), Cologne, Dessau, Frankfurt, Munich, and Weimar, along with the towns along the famous Rhine Valley, have frequently been part of my travels for both pleasure and work. Each of these visits arose from my interest in architecture, history, and culture, and, I will admit, have been slowly checked-off of an endless ambitious list of places that I wish to learn more about. Perhaps selfishly, I am trying to create my own set of 1,000 Places to See Before You Die, which of course, will never happen.

Shame on me for shying away for so long from Hamburg. A recent trip rectified that and brought me to the Hanseatic city. My stay was exhilarating, memorable, and Hamburg has perhaps become one of my favorite cities—despite that this list does frequently change depending on the longing of the moment.

Over a short week, we visited many of Hamburg’s quintessential neighborhoods: Speicherstadt and the adjacentKontorhausviertel; as well as the historic city center with its man-made canals that long served as lifelines for the transport of inner-city goods; the elegant Harvestehude district facing the Aussen Alster lake (where my mother lived as a late teen); two major train stations; and the must-see for any architect—but nevertheless disappointing—contemporary HafenCity with its famous Elbphilharmonie, a landmark designed by Swiss architects Herzog et de Meuron (Image 1, above).

The Hansa city of Hamburg

Hamburg, along with Lübeck and twenty other German cities—not counting adjacent trading posts outside of Germany—were part of what was called the Hanseatic League (Image 2, above). Created between the 13th and 15th centuries as a “commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds,” what remains today is remarkable. For me, beyond the political and commercial vision that traders would belong to the league and thus enjoy duty-free treatment, is the identity and character that was left on the architectural heritage of these cities. While Lübeck was the center of the league’s power, and showcases some beautifully detailed façades, Hamburg’s Speicherstadt became my focus during daily walks outside of our hotel (Image 3, below).

Hamburg’s Speicherstadt

Located adjacent to the historic city center of Hamburg, the Speicherstadt was settled between 1885-1927 and remains the world’s largest port warehouse and office complex. Set over an area of roughly 260,000 square meters, it was established in 1883 following the demolition of existing structures, which was accompanied by the relocation of more than 20,000 people (Image 4, below). In 2015, the entire Speicherstadt site gained UNESCO World Heritage status.

The complex was built on the Elbe River on narrow strips of land, combined with millions of oak logs driven 36 feet into the marshland. The timber-pile foundations allowed the warehouses to resist the daily tide differences of the canals—similar to the principle of settlement of Venice. (Image 6 below).

The network of canals formed in the Speicherstadt is punctuated frequently by steel bridges (Image 7, above) linking warehouses to one another, and connecting the area to the historic city to the north. These bridges always formed the lifelines for the inner-city movement of goods, and helped Hamburg’s Speicherstadt become a world-renowned free economic port district. Prior to 2013, when the economic zone of the Speicherstadt was dissolved, the status of free-port allowed Hamburg to increase trade volume based on their hegemony on the North and Baltic Seas, while increasing capacity in international trade.

The architecture of the Speicherstadt

Having chosen to stay at the Hotel Ameron—the only hotel located in the historic district of the Speicherstadt—curiosity took me on a daily basis on a path to admire the Gothic revival architecture. During my walks, the elaborate colored brick works, buttresses, corbels, decorative gables, friezes, oriels, pinnacles, traceries, and towers with occasional carved sandstone detailing all caught my attention (Image 9, below).

While red brick was primarily used for the exterior wall cladding of the warehouses, sandstone was employed for other elements such as complex detailing and ornaments complementing the brickwork, often negotiating through its plasticity key moments of the overall architectural tectonics. The interior steel columns of the structures were similar to those used in train stations of the era, while wood flooring provided flexibility to accommodate goods of various weight and dimension. Copper gabled roofs gave the overall area a distinctive skyline (Image 8 and 9 above, and 10 and 11 below).

The decorative architecture of the Speicherstadt

Because of the readily available clay found in the northern German plains, the use of baked red brick became a material of predilection for domestic, civic, and religious structures around the region. Furthermore, as brick has per se no aesthetic function in isolation, the warehouses of the Speicherstadt were characterized by a reduced Gothic style—meaning they have a decorative restraint that left out much of the typical figural sculpture found in true Gothic architecture. The exclusive use of brick was true to a certain extent, although sandstone was used to embellish the facades (Image 10, above).

This restraint, through the use of two materials, was so appealing and elegant to me. Furthermore, to study the various facades in the Speicherstadt was to recognize a distinctive expression of the engineering skills of many craftsmen. In their own way, they were able to create a complex yet unified aesthetic solely with brick bondage (to my understanding a modified Flemish bond pattern), using various red and ochre bricks along with a dark black glazed brick, with occasional glass elements to create strong graphics at key moments in the façade. While this façade treatment is not unique to the Speicherstadt, it is nevertheless essential to mention in this context (Image 13, below).

During my research, I discovered three important themes for the usage of brick and the Gothic style:

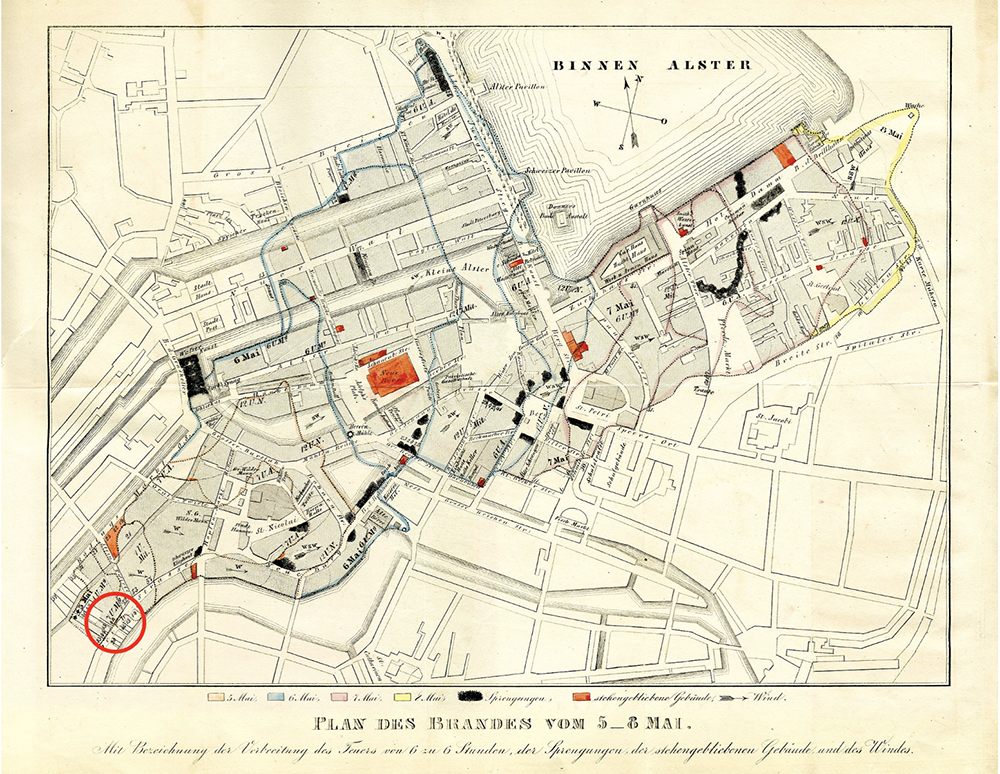

- The aftermath of the 1842 fire that destroyed a third of the buildings in the historic city center (Image 5, above), resulted in the proposal of a reconstruction plan that required the use of brick as wood was no longer permitted. Also, because of the fire, merchants were pushed to relocate their warehouses closer to the docks, which was one of the reasons for the later creation of the Speicherstadt.

- I also discovered that the use of the neo-Gothic style throughout the Speicherstadt cityscape was attributed to the mid-19th century Hanover School of Architecture that was characterized by a move away from classicism and neo-Baroque taste in Germany. Used in many building types, the austere expression of the building’s facades, in our case those in the Speicherstadt, called for unplastered brick facades, which were in their own way, a proto-modern attitude to create buildings that spoke and were to be honest in their expression. A warehouse spoke about its nature of storage, thus suggesting in its building shape and façade treatment an expression of its internal function. This style is often referred to as “Brick Gothic building (Bachsteingothik),” or “Hanseatic Brick Gothic Architecture” symbolizing the powerful regional alliance of cities.

- Perhaps, and most compelling to me, was that for an expanding 19th century German industrialization to take place—one which still needed an expression through past styles as a speaking architecture—the use of the Gothic style allowed a functional “subdivision and structuring of walls [facades],” thus allowing large repetitive windows to occur between vertical structures, of course, allowing ample light into the warehouses.

My investigation into the development of the Speicherstadt led me to study its function and continuity into the 21stcentury with the Elbphilharmonie. This is described in the following blog.

Other blogs of interest

Speicherstadt in Hamburg. Part 2

Street pavement: Wittenberg, Germany

Architectural Education: A question of preservation

Casa Rezzonico by Livio Vacchini, Switzerland

Lessons from vernacular architecture—inventing versus re-inventing