Why Model Sketching? Part 2. As a student attending Cooper Union, I vividly remember the first time I saw one of my peers “sketch” in model form. While I was well versed in sketching through drawing, and was particularly fond of diagraming concepts to develop ideas, I was surprised by this new method of allowing ideas to emerge like in a sketch, but within a three-dimensional context. There was something seamless between idea and representation, between thinking, seeing, and how the hand dances while crafting the model. I was hooked and wanted to explore this new process.

Why Model Sketching? Part 2. As a student attending Cooper Union, I vividly remember the first time I saw one of my peers “sketch” in model form. While I was well versed in sketching through drawing, and was particularly fond of diagraming concepts to develop ideas, I was surprised by this new method of allowing ideas to emerge like in a sketch, but within a three-dimensional context. There was something seamless between idea and representation, between thinking, seeing, and how the hand dances while crafting the model. I was hooked and wanted to explore this new process.

University of Kentucky

A couple of years later, while serving as a young faculty member at the College of Architecture, University of Kentucky, my colleagues and I were fortunate to have José R. Oubrerie (1932-2024, death date added March 2024)) as our dean. As a young man, José studied painting and architecture at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in France, with the additional important distinction that he worked for Le Corbusier (1887-1965) —the celebrated 20th century Franco-Swiss architect—at the iconic atelier located at 35 Rue de Sèvres in Paris. After launching a teaching career in the United States, José’s presence as dean was always exhilarating and at times intimidating. To this day he has a genuine energy and passion for the study of architecture.

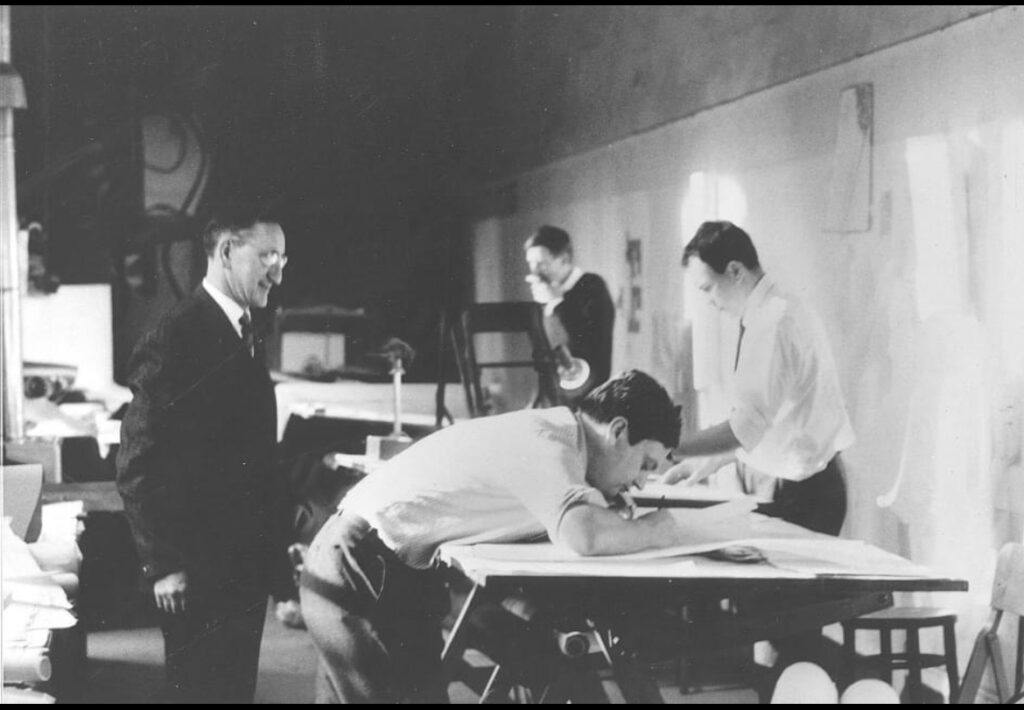

Google images: Jose Oubrerie with Le Corbusier, 1960

Google images: Jose Oubrerie with Le Corbusier, 1960

For architecture students, design reviews—the formal mid-term and final presentations—are key milestones during the semester’s studio project. This is true for every architecture program, but under José, reviews were memorable for faculty as well, and most of us would go out of our way to attend them. Of course, José was at that time one of the last living apprentices of Le Corbusier (Guillermo J. de la Fuente was alive at that time (1931-2008 and had also taught at Kentucky, and Balkrishna V. Doshi (1927-2023 (death date added March 2024)) who became the 2018 Pritzker Prize Laureate), however, we wanted to also see him give a critique—all with a French accent that was incomprehensible to some.

We were eager to listen to the countless stories about his time working under Le Corbusier, accounts that often revealed themselves during reviews as invaluable lessons for students to legitimize their dreams and vision with honesty and integrity. Additionally, we as faculty wanted to attend reviews because the idea of having a dean regularly give critiques—something I had not seen much during my education in Europe—was for all of us an occasion to witness José engage the students, his remarks always honest and delivered with panache, energy and, quite frankly, an aura. An ethical stand that I believe many of today’s students miss receiving.

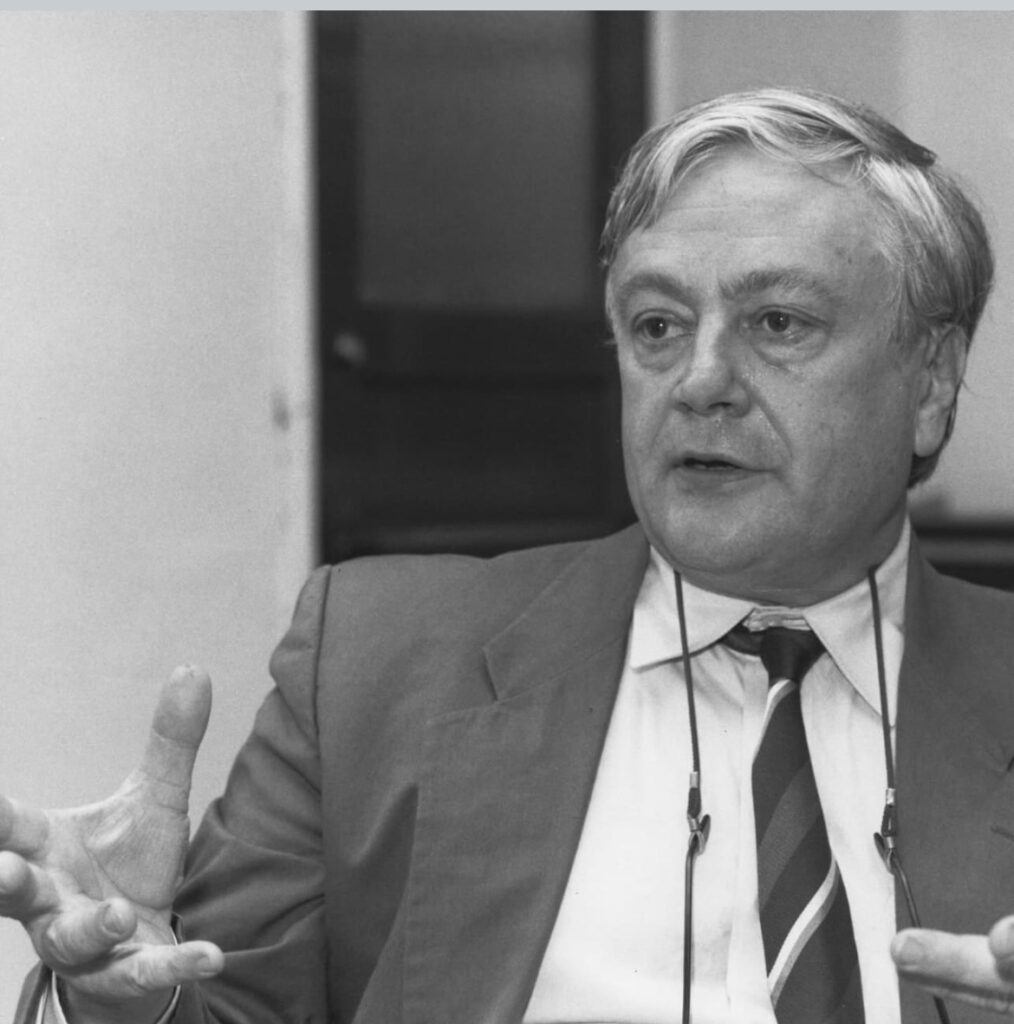

Jose Oubrerie

The real and unspoken reason for the interest in attending reviews was that José has a unique style of teaching, and I remember being fascinated to see how models were disassembled and recombined during reviews, thus creating consternation and mostly frustration among students, but they always had respect and awe for the performance unfolding in front of their eyes.

Between homeopathic and surgical interventions, José’s hands would intuitively and energetically—after a quick yet thoughtful assessment of the “truth” of the student’s verbal presentation—tear pieces off their model, a prized object that had been crafted with love, ingenuity, and daring.

Transforming the student’s “presentation model” rapidly into a “sketch model,” José’s dexterity brought new life to the meaning of the student’s project—without ever giving dogmatic direction on where improvements were to be made. All of this seemed magical and far from the pontification of faculty’s well-versed review tricks that with the self-gratification of a failed genius tended to suggest—and sadly still now—that students simply turn their model upside down, and voilà, they were set to greatness.

Those kinds of statements were not part of José’s tactics, as he was confident about his position in the architectural world. He had this knack—this je ne sais quoi that is hard to analyze or teach—to stimulate the audience and, while excited in his actions, he exhibited incredible intuition and coherence in physically translating his spatial suggestions to the students.

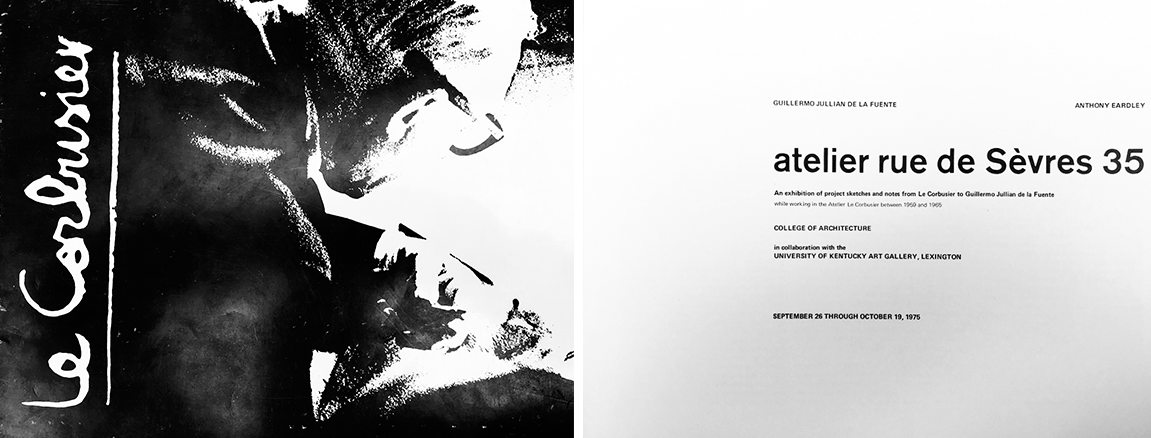

Exhibition catalogue produced by the College of Architecture in collaboration with the University of Kentucky Art Gallery, Lexington, KY

Exhibition catalogue produced by the College of Architecture in collaboration with the University of Kentucky Art Gallery, Lexington, KY

Sketch modeling

I always wondered where this process of sketch modeling originated from, because for me it was the closest approximation to actual pencil or ink sketching and conceptual diagramming. Stumbling on a 1975 book titled “atelier rue de Sèvres 35,” a beautifully illustrated exhibition catalogue on the sketches and notes from Le Corbusier to Guillermo Jullian de la Fuente, I discovered the image (below) of a sketch model of Le Corbusier’s Carpenter Center (1963).

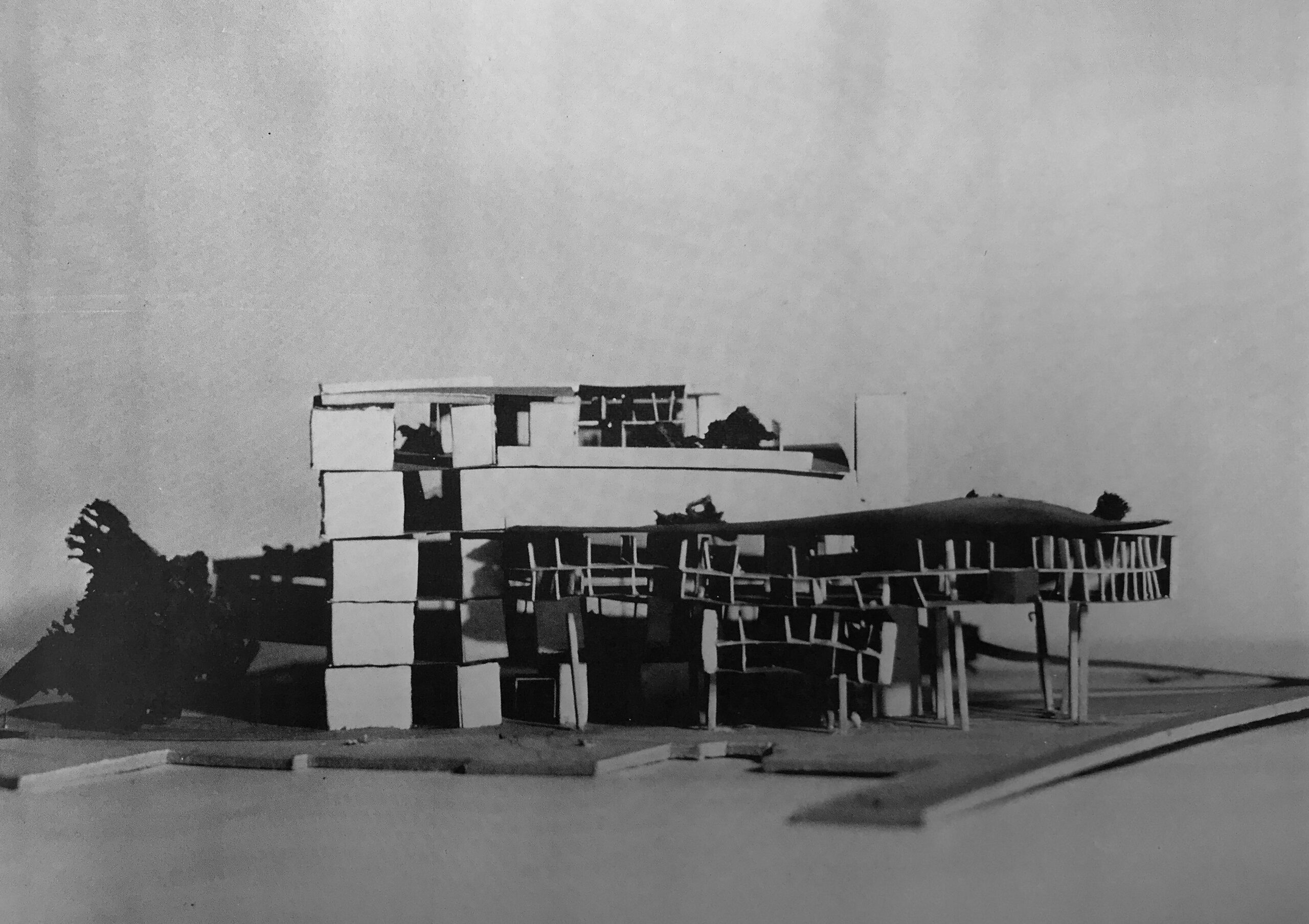

Image from exhibition catalogue

Image from exhibition catalogue

Ever since, I have admired this sketch model for its pertinence in design thinking while its aesthetic elegance never seemed a genuine pursuit at this particular juncture of the investigation. The idea is there, unambiguously with its iconic picture plane from which an amorphous shape protrudes, supported by pilotis (columnar structure) holding up a facade seeming to levitate with small brises soleil. The sedimentation of the floors is rather clumsy, but so correct and expressive of the overall idea of a sketch, but this time in the form of a model.

Student sketch models

As a teacher, I encourage my students to use similar model making processes. While I admire final models—especially those that are restraint and made out of chipboard of identical color—too often students in their first forays into a three-dimensional model, simply duplicate their drawings, mostly with a lack of delicacy in terms of sizing of the various shapes and structural members.

Too boot, if a minimum set of limits is not established, students will use any purchased or found materials, color, texture and size—even leaving at times the barcode on wooden dowels used for columns—and this regardless of any intuitive estimation of what dimensioning implies. The latter always baffles me: Why are students not taught the art of seeing that goes beyond looking and observing around themselves? Instead they feel the pressure of creating something ex nihilo without much attention to their spatial reality.

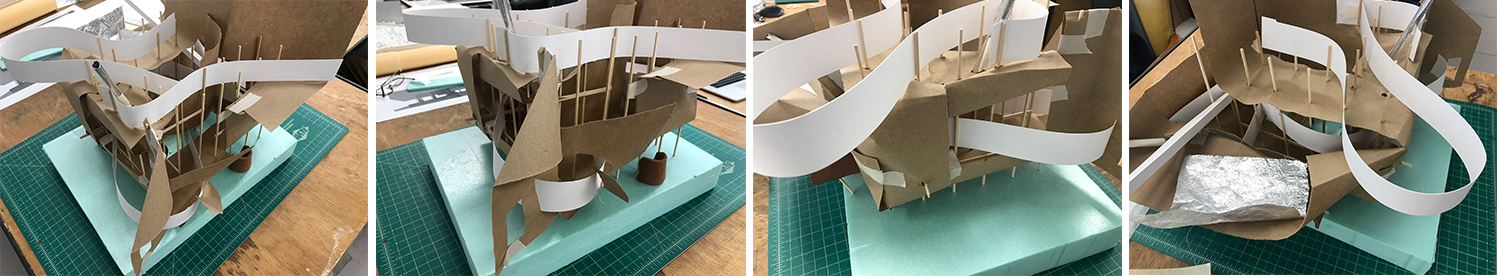

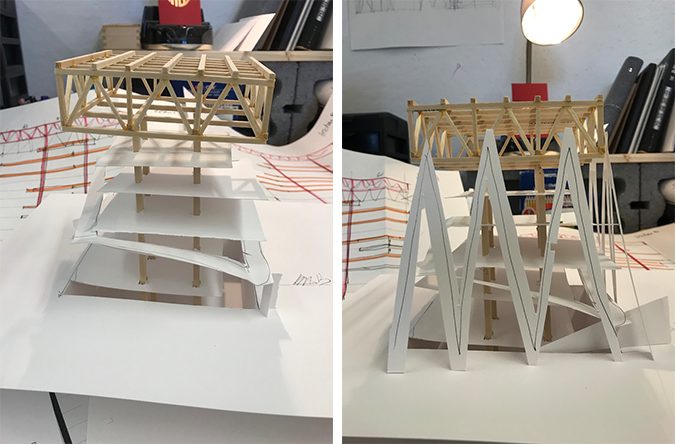

Undergraduate thesis student’s sketch model

Undergraduate thesis student’s sketch model

While typical model making offers great learning opportunities and endless freedom, completed models at this early stage of the project’s development tend to impoverish the nature of what they need to convey. They rarely express the conceptual ideas that are so critical to advance the architectural process. Yet, in all honesty, the models done after the sketch model also remain important as tools to visualize space, as students can learn so much by cross referencing their drawings in a three-dimensional representation.

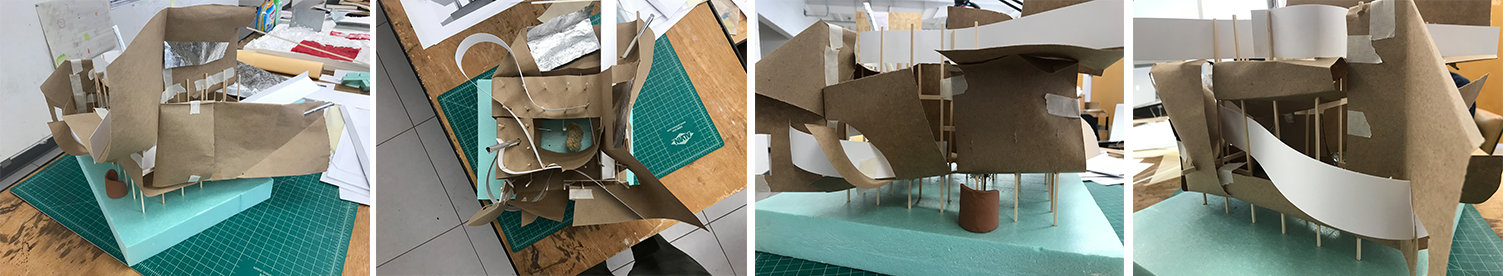

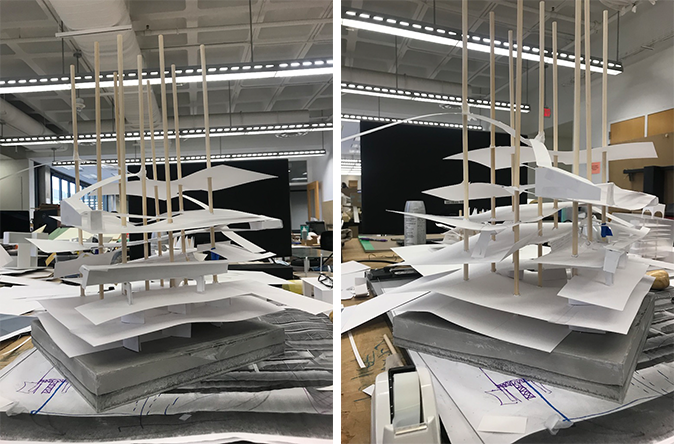

Undergraduate thesis student’s sketch models

Undergraduate thesis student’s sketch models

Iterative sketch modeling

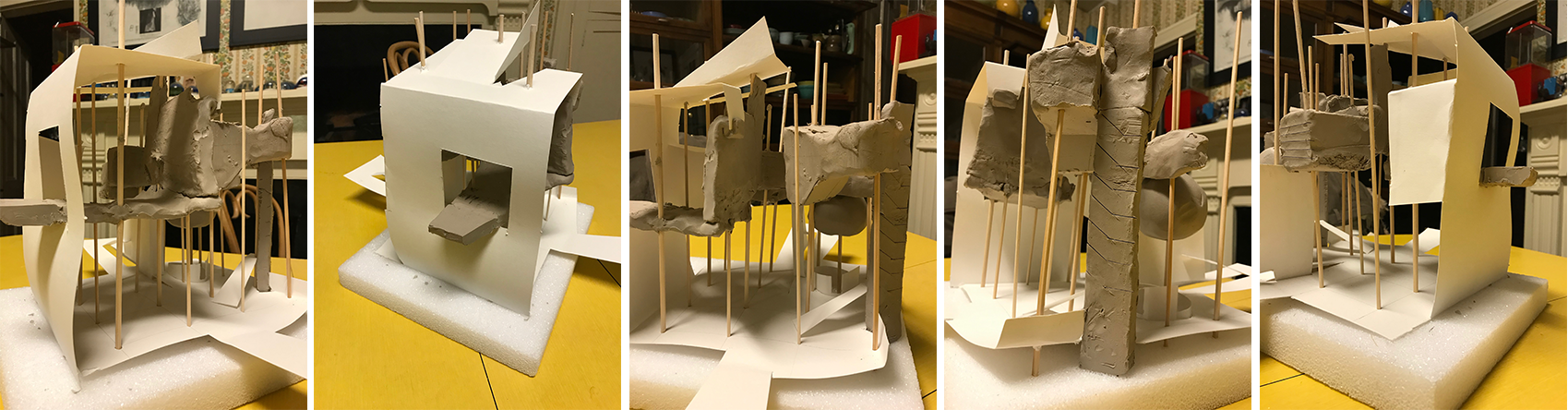

Sketch models are different, and while encouraging the use of a variety of materials, the idea of building the object is to move rapidly in “designing” the spatial idea that has been in one’s mind, or in drawing. Techniques of curving and folding Bristol or Butcher paper offer immediate structural opportunities that avoid glue and the need to wait till it dries. Tape of any sort can be rapidly placed to hold surfaces together without losing the momentum of creating. Often a base such as a discarded piece of Styrofoam may be used to hold a columnar structure, allowing it to provide support for floors, walls, ramps, stairs and roofs.

All of these moves translate imprecise thoughts; thus, I encourage students to work with continuous paper surfaces that extend far beyond the area of interest. This for the sole purpose to allow the model to “dictate” moves where boundaries can be folded, bent, or cut to signify spaces, edges, surfaces and vertical transitions through a seamless piece of paper.

All of this may be done by cutting paper with scissors, an exacto knife, or simply by doubling the paper to give the desired visual dimension. Time is of the essence to maintain a seamless process between thinking and making, and this model making technique is so similar to sketching on paper. Finally, the question of scale remains tricky in this process, and my suggestion is to work at scale as a relationship between elements, and not scale in terms of architectural scale (i.e. 1 ½”=1’–0”).

Graduate thesis student’s sketch models

Graduate thesis student’s sketch models

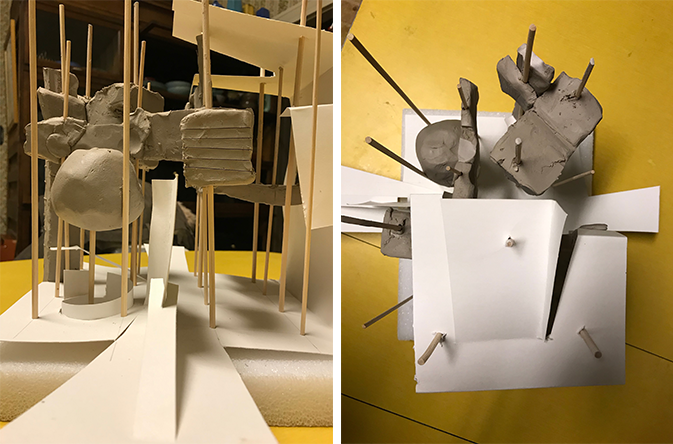

As a student embarks to sketch in model form, I will admit that this skill—as a rough and rapid means for spatial discovery—is a difficult subject to explain, as it is easier to demonstrate in person than to describe the process in written words. It is such a physical, intuitive, rapid and highly personal activity that the word process does not do it justice. But give it a try and you may see how a new world will open for you.

Author’s sketch model to introduce students’ to this design process

Author’s sketch model to introduce students’ to this design process

Conclusion

On a concluding note, with the challenges that each of “our” architecture students face in their studies due to the health crisis of Covid19, I admire their tenacity in setting up “shop” wherever they can while waiting to return to their respective campus studios. Having visited numerous offices, some which are as big as small museums with all the bells and whistles, I cannot omit to share the image of Le Corbusier’s atelier (below), one that seems vast but minuscule compared to contemporary work places: a place “…of the man [Le Corbusier] who fashioned his austere practice in that sparsely equipped cloister on the rue de Sèvres into the most extraordinarily powerful architectural engine of the first machine age .”

A great lesson that reminds me that genius only need a work surface and a healthy dose of confidence and intuition.

Google Images -Atelier Le Corbusier, 35 Rue de Sèvres, Paris, France (Jose Oubrerie far right)

Google Images -Atelier Le Corbusier, 35 Rue de Sèvres, Paris, France (Jose Oubrerie far right)

Google Images -Atelier Le Corbusier, 35 Rue de Sèvres, Paris, France (Jose Oubrerie front right)

Instagram -Jose Oubrerie far left, Prof Jerzy Rosenberg, sitting -Prof. Whitney, Prof. Maria Grazia Dallerba-Ricci. and Prof. Michael Jacobs far left standing

Instagram -Jose Oubrerie in the Miller House

Google Images -Jose Oubrerie

Google Images -Jose Oubrerie with UK faculty Michael Jacobs and Bruce Swetnam (sitting)

Google Images -Jose Oubrerie while serving as Dean at the University of Kentucky, College of Architecture.

Google Images -Jose Oubrerie

Google Images -Atelier Le Corbusier, 35 Rue de Sèvres, Paris, France (Jose Oubrerie with Le Corbusier discussing the church of Saint-Pierre in Firminy, France. This project has an incredible story and was completed in 2006 by Oubrerie)

Additional blogs of interest

Architectural sketching and how do I sketch

The importance of sketching for architects, Part 1

Some thoughts on sketching by hand

Sketching on a field trip, Part 1

Sketching on a field trip, Part 2

Issues about sketching, Part 1

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 2

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 1

Architectural Education: What issues does one encounter when sketching?

Why Model Sketching? Part 5

Why Model Sketching? Part 4

Why Model Sketching? Part 3

Why Model Sketching? Part 2

Why Model Sketching? Part 1