Architectural sketching and why is it important.?This blog is part one of three on sketching architecture. This one introduces aspects about my own sketching techniques and their origins, and how sketches and architectural drawings were seen as works of art.

The second blog will use a number of my personal sketches to illustrate how they can help with discovery in research.

Sketching as a kid versus a professional

Since childhood I have enjoyed sketching, clearly this was well before thinking of studying architecture. Sketching as a particular mode of drawing seemed to come naturally to me. First, as a kind of self-expression, which slowly turned into a way to visually communicate my feelings. Those early sketches were naïve depictions typically filled with wild, exaggerated fauvist color schemes. We all know what kids’ drawings look like, and I am proud to have contributed my fair share of them to my parents and kindergarten teachers.

“Yes. As I’ve often said, I think being able to draw means being able to put things in believable spaces.”

David Hockney, British painter

Later, while enrolled in architecture school, sketching became a way to learn about the world while trying to set my imprint on the profession by translating ideas into space. At the end of my studies, sketching turned into an extension between mind and hand and became a way to visualize my curiosity towards the world. Sketching by then was a trusted companion, and through daily practice I was able to express my creativity. This has become a lifelong endeavor both professionally, academically, and as a hobby.

I will admit that honing my sketching skills was far from easy, despite my early affinity for drawing; especially when I reflect on the way I sketch today. I often tell my students that for most of us, sketching is NOT an inherited skill. We gain our facility—and confidence—by sketching on a daily basis, by setting ideas on paper without being ashamed of how they look or worrying how they will be perceived by others. As long as an author is genuinely committed to express their thoughts with clarity, confidence, and commitment there is no reason that a convincing AND meaningful sketch cannot naturally follow suit.

Two attributes of my method of sketching

1. Quality of line

After several decades of praxis, I can discern in many of my sketches a connection between those done during my architecture education and the ones produced today. I believe that what is most important in them is that the overall line weight lacks precision. Not because of any trembling in my hand—each line exhorts decisiveness—but I believe that when sketching is used as an observational tool it serves to understand and think beyond what I have in front of me. Thus, lines are fluid and accompany my thinking process.

In a certain way, this is in opposition to the idea of simply recording what I see. If that was my intention, an iPhone would accomplish the task in a nano second and provide ample information to later appreciate and analyze via the photograph at home. Personally, I favor using sketching to record what I am trying to understand; an intent that benefits from an on-site presence. However, this type of sketching can also be applied to observing buildings on, for example, a social media platform.

2. Lines juxtapose and overlap

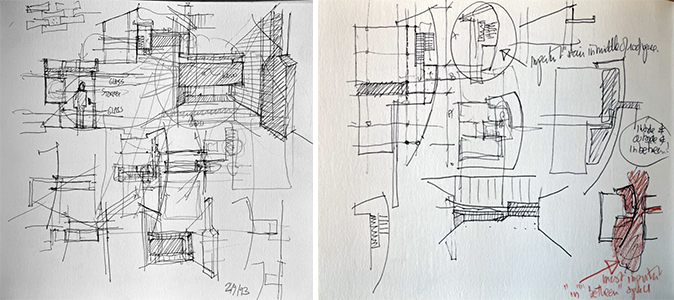

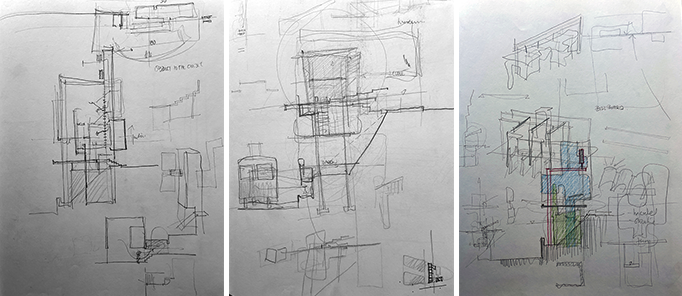

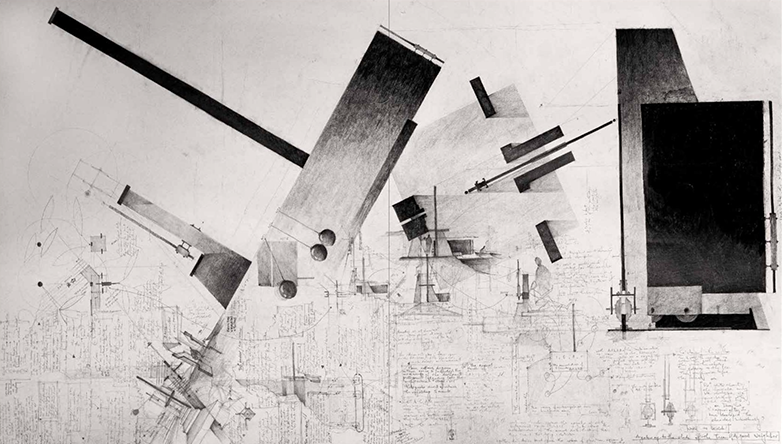

The second attribute about the qualities of my lines—either as an observational tool or when designing a project—is that because of the rapidity of my sketching technique my hand is catching up with my speed of thought, resulting in a profusion of ideas, so that lines juxtapose and overlap across forms and geometries. The sheer fact of having lines tending to overlap, allows for multiple readings. This provides me with the ability to continuously further my investigation without pinning down or being limited to one single idea (Image 2, above).

Cubism and purism

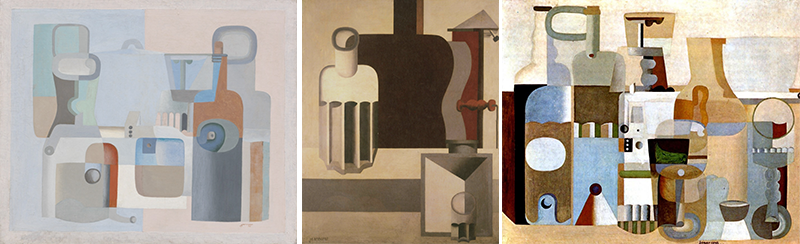

Both ways of sketching (decisiveness, and juxtaposition with overlapping lines) were introduced to me by one of my second-year professors, Robert Slutzky. Because he was first and foremost a painter, who also co-authored one of the seminal books about architectural and pictorial transparency, he opened up to me the beauty and subtlety in understanding the cubist and purist pictorial world (Image 3, below). Ever since then, I have been enamored with those paintings.

As abstract still-lives, many of these paintings allowed me to not only contextualize two key artistic movements of the early 20th century (cubism and purism), but more importantly, allowed me to interpret them by creating three-dimensional architectural spaces where typical functional and programmatic boundaries were now blurred.

What fascinates me in these paintings is that there is a deliberate intent to paint in a way that offers multiple readings of the objects. This is achieved by juxtaposing and overlapping lines of recognizable geometries, suggesting edges and contours that belong to multiples objects. Lines are in fact an interface between two adjacent or intersecting forms.

In addition to this representational strategy, I have always been enamored with the treatment of a horizon—originally suggested as the edge of a table on which these objects have been placed—that now navigates from top to bottom depending on the viewpoint of the painter. Noteworthy is that we can find the theme of the horizon being addressed and incorporated in architecture in many different ways.

Over time, I have come to sketch in a way inspired by these pictorial representations, especially during brainstorming sessions, be it on an architectural project, a desk crit with students, or taking notes that explore tangential future meanings beyond the content of the text or project under scrutiny.

This technique of sketching reflects how my mind meanders without preconceptions or being willfully ‘precise’. I have often mentioned in past blogs that I aspire to be a flâneur when visiting cities and I now realize that I sketch in a similar manner. Most often I let sketches bring me to new places that I would have not immediately thought of investigating. I have always favored this way of sketching, which purposively counters the stance of ‘I always know what I want to draw.’ I believe that the latter approach avoids growth and surprise, and may stifle maturity in the design process.

Thus, many sketches become a nuance of each other by adapting different line qualities that slowly contaminate the progression between one sketch and another, without ever losing the ultimate aim that is to bring out a larger conceptual idea. Therefore, in this mindset, lines cannot be precise, they must overlap and juxtapose, allowing my mind to meander.

What is sketching?

I believe that there is no perfect definition, thus let me state that sketching to me is first and foremost a matter of individual character. It is fundamentally autobiographical, and as stated above, one should have no shame in how one sketches. In a world where digital tools, robots, and, not so far in the future, Artificial Intelligence (AI), can design, draw, construct, and literally build our ideas, sketching will remain a strong testimony of our human intelligence and understanding of the world in a sensory way. Therefore, it seems ever more timely and significant for designers to practice this art form on a daily basis. For this reason, this blog will explore some of the meanings of sketching.

1. Sketching as art

After including many of my sketches here, I want to state that none of them are works of art. For me, sketching is about process; a moment of discovery surrounding important questions. I have my own style and repertoire, and yet I am heir to a sketching tradition. This is because I have followed intellectually in the path of many architects of the later part of the 20th century who have included in their quest both process AND discovery.

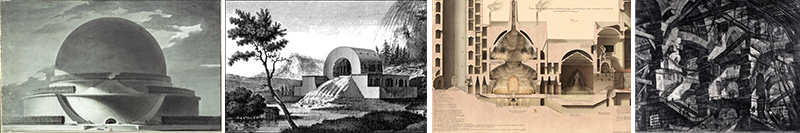

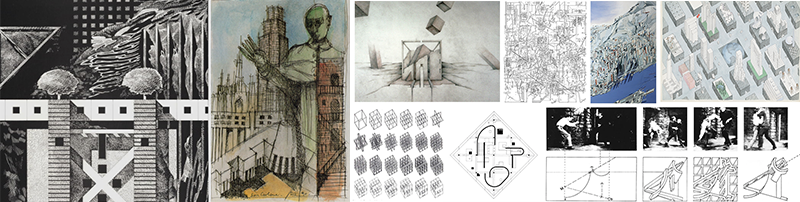

To a certain extent, the ambition of these architects relied of previous architects of the 18th century (Boullée, Ledoux, Lequeu, and Piranesi) who strived to express innovative and experimental ideas without having to build them. The artifacts expressed as drawings, paintings, and more importantly as architectural renderings, blurred the boundaries between architecture and art (Image 5, above).

New York City

This desire to blur boundaries was true for many architects theorizing at the time of my studies in the early 1980s in New York City. The resurgence of drawing AS Architecture (with a capital A) led many architects to be preoccupied with producing ‘final’ works of art, moving away from sketches to architectural drawings, renderings, and models.

Architectural boundaries were exacerbated during the Reagan era and art galleries enticed architects to exhibit their work with a clear agenda to steer those artifacts as financial commodities to a clientele of new wealth; often called yuppies. This added mercantile value was a major difference that defined architecture at that time. These so-called “paper” projects (scenography and visual; sign and symbol), seemed to be now more anchored in art rather than as spatial endeavors accordingly to Vitruvian principles. All this while buildings promoted a postmodern language where styles were borrowed and no longer carried an intellectual dimension.

Select non-commercial architects were part of this emerging art and architecture scene that took place in New York’s Soho district. Many of them (e.g., Raimund Abraham, Emilio Ambasz, Peter Eisenman, Michael Graves, Zaha Hadid, Hans Hollein, Leon Krier, Rem Koolhaas, Gaetano Pesce, Aldo Rossi, Massimo Scolari, Bernard Tschumi) were featured in galleries such as Leo Castelli (Architecture III: Follies), Storefront for Art and Architecture, and the famed uptown Max Protech (Image 6, above).

With my roommate Michael, who also studied architecture, I would make a point to scout out these galleries and attend each of them during opening nights. Not simply to admire the drawings and meet the leading protagonists, but to snap up a free catalogue and enjoy food on the galleries’ tab.

A little earlier in the 1980s, the Architectural League of New York—where I would later work, assisting with the Thursday lectures—was part of this inquiry discussing the relationship between art and architecture. The League, as it was called among architects in the city, held an exhibition in 1981 to honor the League’s Centennial. They “commission[ed] 11 teams, each with a leading architect and an artist, to come up with a visionary project relevant to the problems of the decade ahead. The results range from the practical to the polemical, but all have something to say about the ever-changing relationship between the architect and the artist.”

All in all, there was an incredible aura at that time around architectural drawing, art, and street art that gave the city its vibrancy as a place to study and enjoy a somewhat bohemian lifestyle that regularly included moving from place to place between apartments.

On a side note, in 1995 this precise question of a possible dialogue between art and architecture led me to co-launch a graduate studio/seminar at the ETH-Zurich, based on the following questions:

A?A

can contemporary Art be contemporary Architecture?

must architecture be building?

is there any need for architecture in present society?

Conclusion

The semester’s findings complemented much of what I mention above, to the exception that models replaced the flat artifacts so admired in earlier galleries. The work of one of the students was summarized in a blog titled: Question of Pedagogy, Part 4

Closer to today, in 2019 the above topic of the act of architecture and art was explored by one of my students, Aayush Das Anat in his thesis, which postulated that writing and drawing could be architecture. The above panel (among six, which are featured in a different blog) represents the culmination of a year-long research where the final deliverables showcase process. The entirety of the thesis can be found at Issuu.com. It is an excellent example of how sketching is an artform in itself.

Additional blogs of interest

Architectural sketching and how do I sketch

The importance of sketching for architects, Part 1

Some thoughts on sketching by hand

Sketching on a field trip, Part 1

Sketching on a field trip, Part 2

Issues about sketching, Part 1

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 2

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 1

Architectural Education: What issues does one encounter when sketching?

Why Model Sketching? Part 5

Why Model Sketching? Part 4

Why Model Sketching? Part 3

Why Model Sketching? Part 2

Why Model Sketching? Part 1