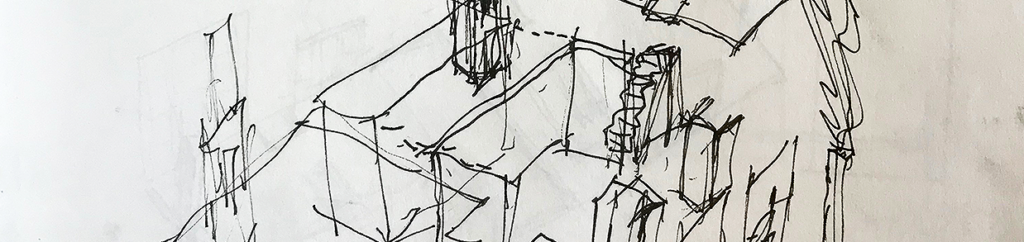

Some thoughts on sketching by hand. Regardless of the nature of an architectural project, students need to produce sketches, diagrams, plans, sections, axonometrics, perspectives, collages, and text in addition to physical models, in order to document their process, as Ilse Crawford defines, as the thoughtful sequence of decision making.

The tradition of sketching

When discussing student sketches, I realize that the quality of their drawings varies widely from average to well-thought-through, occasionally showing exceptional graphic dexterity and effective communication skills. At the institution where I currently teach, we emphasize student sketching—especially during off-campus trips. Yet, I repeatedly ask myself how often we mentor the students to help them develop a range of sketching skills, as the traditional architectural drawing class is no longer taught. Thus, due to the lack of a formal setting for the students, it is up to each design studio faculty to impart representational skills within the design studio context, potentially taking away from time spent learning how to design a project (e.g. 1. architecture project, 2. theory of the project, and 3. theory of the act of projecting).

One might argue that prior to sketching, there needs to be an idea (like the causality dilemma of the chicken and the egg). Pragmatically, a sketch starts with the simple act of holding a pencil. Oh, yes, you should see how this generation of students hold their fingers around a pencil. Most of them, clumsy to say the least, grip the pencil so tight that there is no potential for spatial movement where the gesture of the hand’s fluidity dances in space, much less negotiates the pressure to calibrate “expressive line character” on a piece of paper.

Digital sketching

Both skills—correctly holding drawing implements and understanding how to use them—may seem rudimentary requirements in college. Assuming that these skills are mastered, the bigger question at stake is how students learn to conceptualize, diagram, record, invent, and discuss their ideas or those of others through sketching.

Simply stated, to achieve ease in communicating spatial thinking, I believe that sketching may need to be—along with the classical teaching of color theory, life and figure drawing, and the introduction of various other techniques—formally reinstated. At the same time, daily practice is necessary so that students can seamlessly coordinate ideas back and forth between mind, eye, and hand*. Learning online during the Covid-19 pandemic required digital sketching, however, even before that, analogue sketching was becoming a lost art.

*In a recent studio charette about translating ideas onto paper, I excluded the important component of sight—deemed necessary for discovery and the power of suggestion of the sketch. This allowed me to test the student’s ability to approximate between their mind and hand. The graphic results were fascinating and will be the topic of an upcoming blog (link added 09.19.2022).

The contemporaneity of digital tools

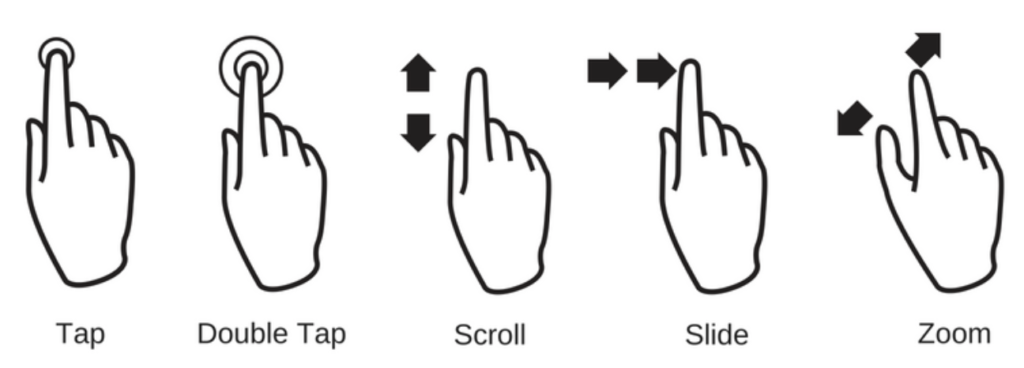

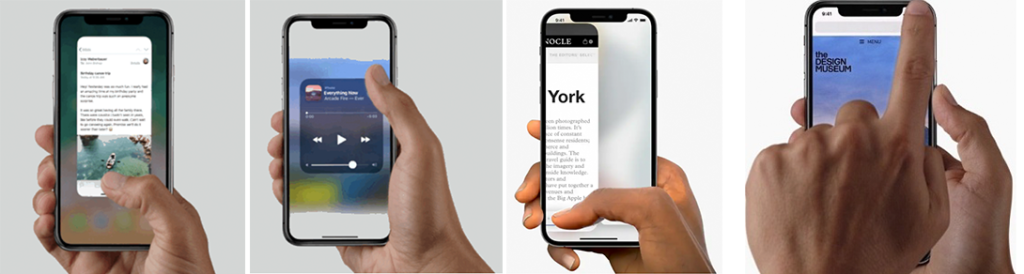

The tap, scroll, swipe, and zoom gestures—rendering obsolete the mid 20th century stylus—are today’s universal user-screen motions through which we interact with smartphones, touch-screen laptops, cash registers, and information/check-in kiosks to name only a few machines. The typical visual support of these gestures is a display that is truly ‘at one’s fingertips.’ These displays have allowed us to migrate from the 20th century mechanical button, through the handheld pointing device called a mouse—visually comparably to the form of a rodent—to today’s sophisticated finger-driven touch screen, with its revolutionary technology that no longer requires great precision in our hand motions.

These now ubiquitous movements—at least for all incoming college students—seem to no longer require great dexterity even as they have become second nature. These gestures are no longer spatial, or help engage students in spatial thinking or spatial imagination with their hand. They are two-dimensional hand movements acted upon a flat screen; a display that offers a planer surface, commonly pocket sized.

Consequences of digital tools

These welcome digital revolutions are often accompanied by a specific mentality in which a generation of students has been taught by the time they graduate high school to get an assignment, respond with a solution predetermined as correct, often mimicking the exact approach devised by their instructor. Sketching—architectural sketching—should remain a process, and not a series of predetermined gestures like a tap on Instagram to indicate liking a post.

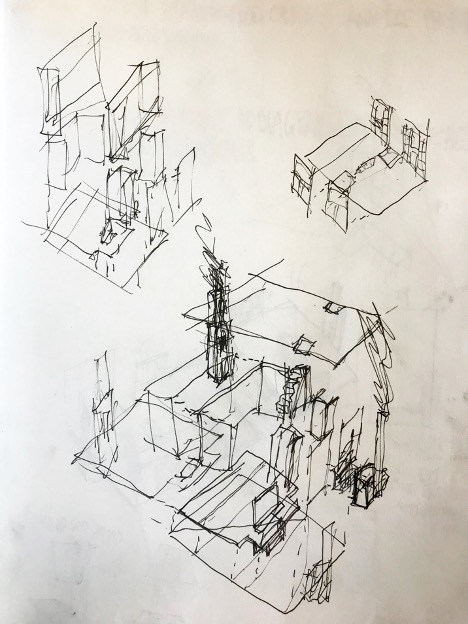

We know how these attitudes have become prevalent in college and how they are counterproductive to any design field where the act of design thinking is paramount and often finds delight in back-and-forth thinking (sketching), with its obvious, and welcome, errors. In this environment, I stress to students the need to sketch, regardless of their skill level, then to slowly calibrate the drawing, leading to a richness in spatial intelligence AND excellence while keeping “multiple design outcomes in play during the early stages of design.”

I often compare designing to cooking, where techniques are mastered to create a sumptuous dish—notwithstanding the need for chefs to have passion, be willing to invest time and hard work, and exhibit a balance of common sense and genius. At the beginning of cooking or sketching is process, and I am reminded of the rumination of David Chang, chef and founder of the Momofuku restaurants: “When I’m working through an idea or a recipe, I like to scribble on a whiteboard: one thought connects to another, to another, which breeds a new insight, and so on, until you have a meandering, interconnected web of ideas encircling the main subject.”

Today, more than ever, students need courage and confidence to embark on a design journey carried out through sketching. They must shift from the idea of producing a single artifact (a drawing that they believe is, in its first instance, perfect and represents a definitive solution), to an iterative process which will include mistakes. This is a lot to ask from this generation. To be successful, students need to take ownership and trust their instincts, become individual thinkers and not automatons, all the while building confidence within their chosen educational path.

Conclusion

Asking students to appreciate early sketch muddles remains critical as they learn to discover the hidden meanings their sketches suggest; an approach that allows them to discover unforeseen opportunities within their drawings. In these instances, students should embrace the aesthetic clumsiness of their sketches (as least in the formative years). Sketches convey an authenticity of ideas that carry meaning for subsequent moves in the project.

Accompanying this thought, I have always insisted that students safeguard each sketch or drawing, simply because they reflect a process. It is one of the most tangible ways to see and reflect on decision-making as it relates to their design. This allows them to understand their journey and process in a meaningful way.

Additional blogs of interest

Architectural sketching and how do I sketch

The importance of sketching for architects, Part 1

Some thoughts on sketching by hand

Sketching on a field trip, Part 1

Sketching on a field trip, Part 2

Issues about sketching, Part 1

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 2

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 1

Architectural Education: What issues does one encounter when sketching?

Why Model Sketching? Part 5

Why Model Sketching? Part 4

Why Model Sketching? Part 3

Why Model Sketching? Part 2

Why Model Sketching? Part 1

Problem? What Problem?

(In response to Henri de Hahn’s 14 June 2022 Post on Sketching)

George Dodds

There is little about which we are not in complete agreement, Henrei when it comes to the value of sketching in the architect’s productive act, nor do we seem to disagree on such weighty matters as the critical roles of site, history, and materiality, in the making of an architecture.

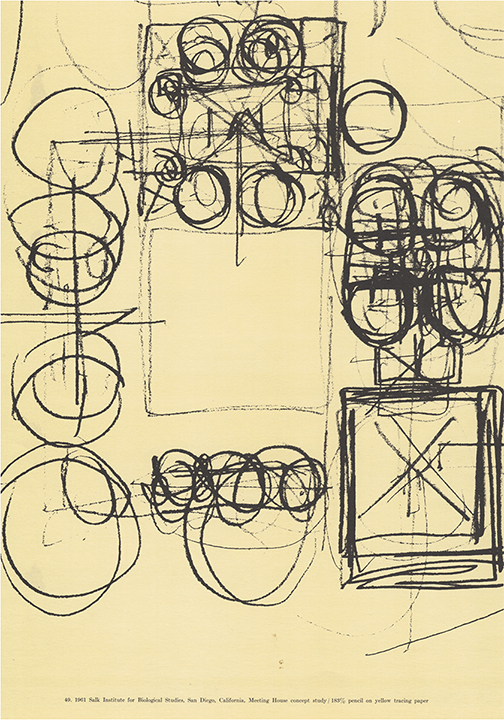

That said, the Kahn diagrammatic sketch of the Meeting House at the Salk Institute, in many ways crystalizes the increasingly difficult time I have reconciling the profound differences between many of the students I try teaching today (whether it is in design studio or in seminar), with those of 35 years ago, particularly in relation to hand drawing, and specifically the value of sketching. The majority simply do not see the point of it, just as they do not see the value of distinguishing between a “render” (a word that does not exist in noun form in the English language – it is the nominalization of a verb) and a perspective (the latter being one of the foundation stones of “modern” architecture if we recognize the Italian Renaissance as the epiphany of Western avant-garde and art theory).

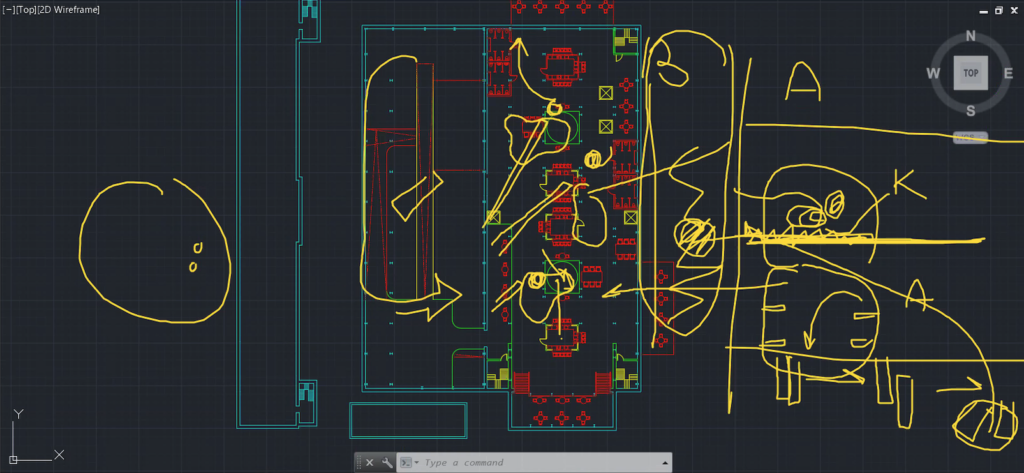

My students invariably depend on software programs from the very start to represent things for them and in so doing, give up far more authority to the software than its programmers ever intended; the designer becomes the tool. Invariably working from a whole form, from the outside to the inside, then filling it with “stuff” (AKA, “program”) issues of inhabitable space – their qualities, nuances, differences owing to type, proximity, custom – are elided in lieu of hyper-specificity of effects and affects, surrounded by entourage grafted from innumerable websites. To those who ask, “what is so wrong with that?,” I answer, everything.

This past semester consciously I worked against this vacuous mode of production, requiring hand-made sketches in chiaroscuro of the three major spaces in the intended project brief which they later knitted into a plan and section on the site. This was not met with open minds; rather there was much skepticism that pervaded the term; one student, in particular, simply ignored the studio pedagogy and designed using her favorite software and then, worked backwards to make the hand drawings – invalidating and irradicating the entire learning experience. (She also claimed that winters were not darker than summers, did not tend to be dreary, and it never got hot in Barcelona! It was along semester.) I’ve had students on foreign study tours who, when time came for site drawing, I discovered sitting in the shade with their backs turned away from the primary building, copying images from their iPhones!

Sadly, our school has all but killed the tradition of architectural drawing just as they have killed the knowledge-base of inhabitable space in general. Students no longer know how to “cut a section.” Just as there is a button that reads “render,” so too is there one for “section.” When I asked why a student did not “jog a section” rather than cut through a set of columns (making the interior seem like a columbarium), she thought I was kidding as that is what the software required. It has come to that in some places. What is to become of these “students” I’ve no idea. When they are confronted with new information, rather than accept it as part of their growing repertoire, they have a tendency to be defensive and suspicious, circling back into the safe world of what the software ostensibly dictates, simply because they have not learned enough to master and control the software.

These are such basic concepts to teach and yet require fertile soil in which to grow. Otherwise, there is only the digital serpent swallowing its own tail.

It’s a problem.

Great read! While living in D.C this summer it is my goal to do a sketch a day of the city.

You raise a valid question when you mention, “how often do we mentor the students to help them develop a range of sketching skills?” Because I believe there can be a lot more of that. There was almost no mentoring within studio on sketching. It seemed like we were meant to magically inherit the skill without ever really being taught it and any sketching ability we had, was the ability we came to school with.