Issues about sketching, Part 1. As an instructor, I have always enjoyed sketching with students. It is among many rewarding rituals that first and foremost establish a complicity. Learning-by-doing—in this instance to see and experience how others practice a particular skill—seems at times an old-fashioned method, but why not continue a well-versed tradition?

As a student, I remember being given the freedom to learn on my own, while also watching faculty craft in real time their verbal critique through sketching. This experience was eye opening. Watching them conceptualize my thoughts, certainly through their own lens, allowed me to understand how I could better express myself. I wanted to emulate their dexterity when I set ideas on paper, something I will admit was far from easy to do.

Within that context, I also learned that the input of faculty when sketching with students has some drawbacks. I would like to share three challenges I have encountered in the process, in particular with students in their formative years.

1. Question of form

Being ambitious is a virtue designers must possess, especially when working on a project. It is a sine qua non condition to create something appropriate that, at least for me, reflects a social aspiration to improve the quality of life of those who will interact with any designed object; from product to landscape to building. “How one experiences a room, how one feels being in a room,” is an important aspect of design, and follows a designer’s aspiration to prioritize how humans interact with space. In other words, designing is about developing empathy for future users.

For students, using traditional systems of notation—analog or digital—emphasizes that experience is first and foremost visual. Yet, sketching in every sense of the word, cannot simply be a visual language. It is a thought process that investigates a sequence of decisions that start with a strategy that prioritizes people. It is about our ability to set the human experience center stage, preferably at the beginning of the design process. Therefore, I stress that the geometrical bravado of a plan does not always lead to a beautiful space; one where a functional interpretation reflects a model of life, a lifestyle, and creates a sense of well-being.

Ask any designer how they translate their vision into reality and inevitably they sketch. This is regardless of if they are in architecture, interior design, industrial design or landscape architecture (the programs that form the School of Architecture + Design where I currently teach), or other design fields including fashion, illustration, automotive, costume, footwear, graphic, stage, and typeface.

Concept versus form of a building

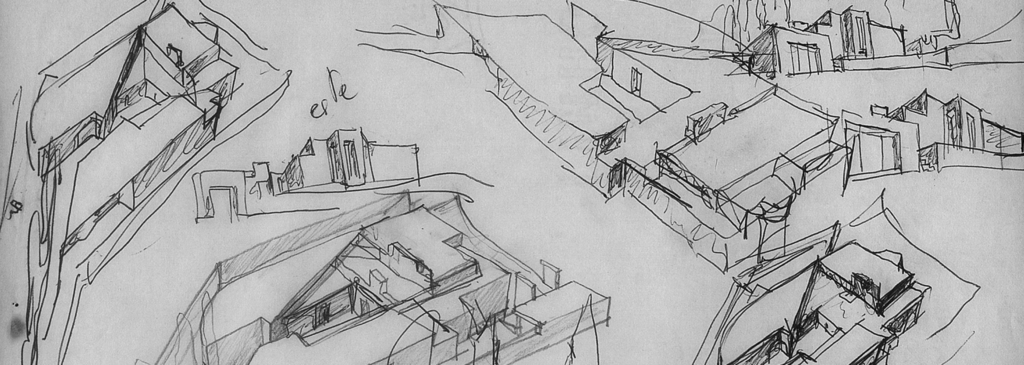

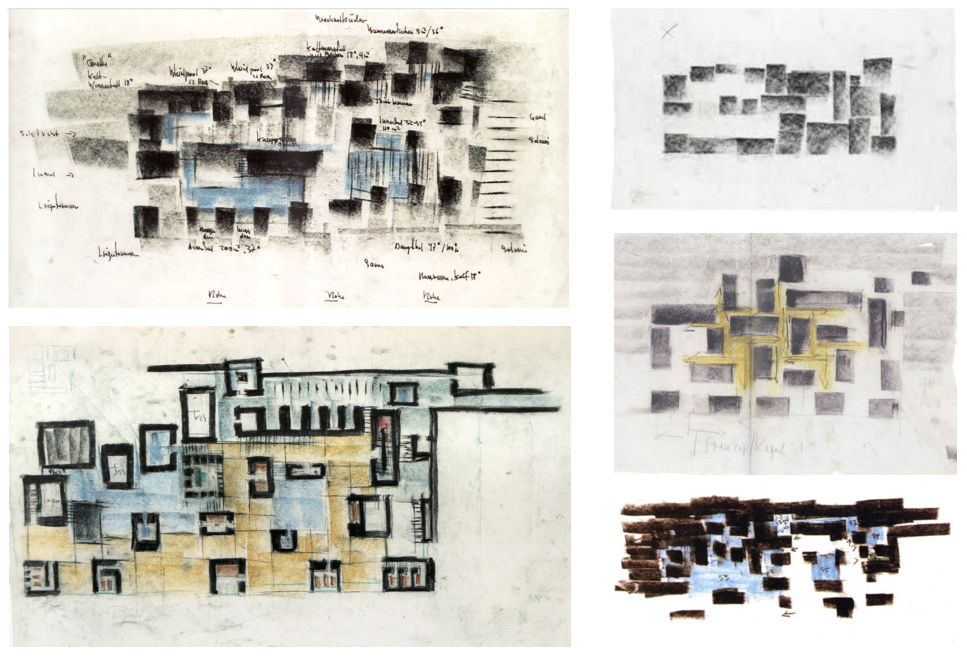

Over the years, I noticed that when it comes to their early sketches—at least in the discipline of architecture—students too often understand sketching not as setting in place concepts or geometries indicative of form (understood as geometry with meaning), but as the actual and final form of their building. The sketch is the design.

A student’s tacit understanding to equate concepts with the final form of a building is difficult to counter because this stand is natural for any beginner in architecture. During my early studies, I made similar assumptions, and with the guidance of my instructors, slowly came to understand the difference between a sketch and a final representation of a building.

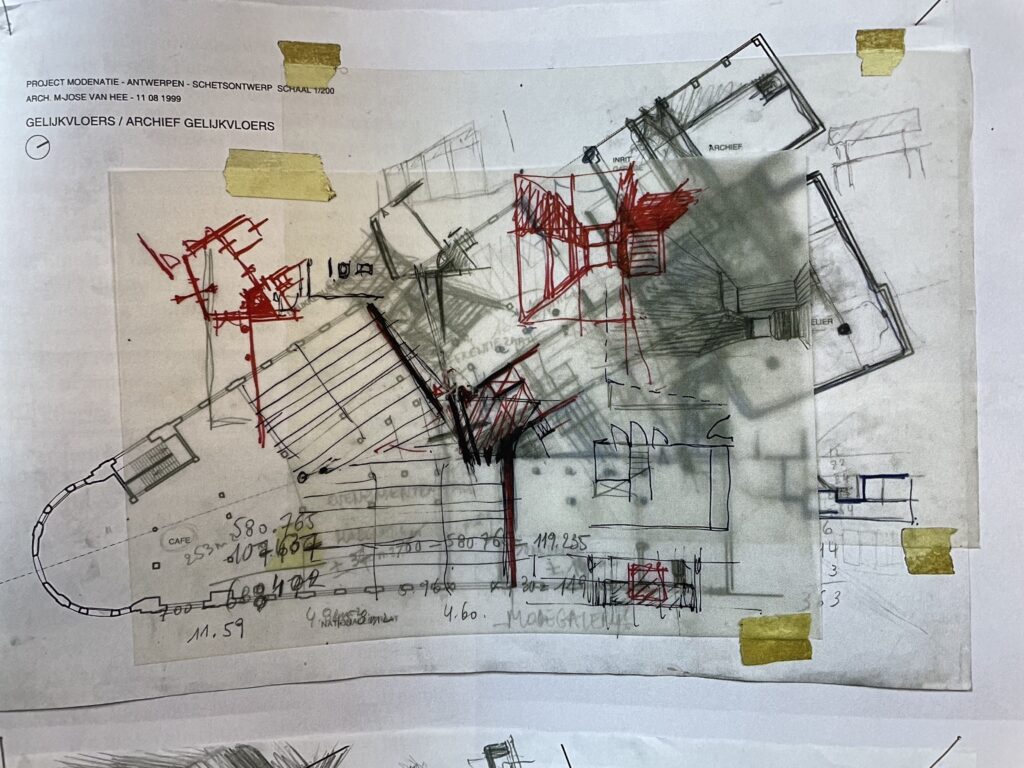

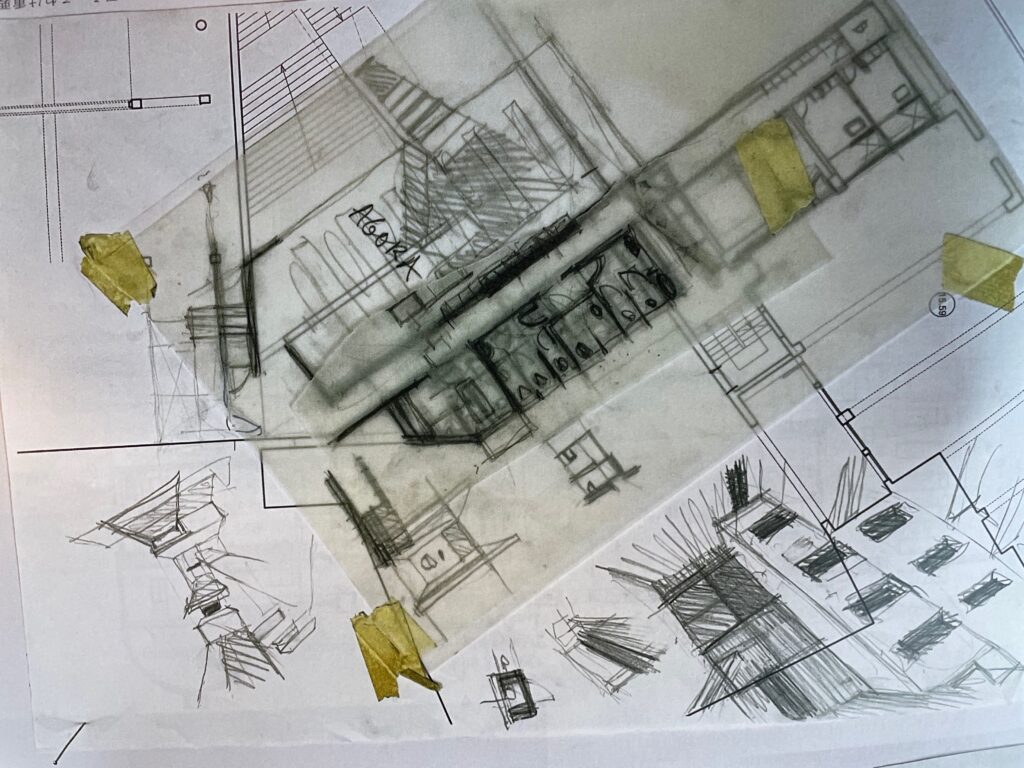

Today, and with increased insistence (perhaps the influence of an Instagram culture), I caution students that what they see when I sketch and what they perceive when THEY sketch, should be part of a world of ideas, especially at the beginning of any project. As one matures as a student, and later as an architect, sketching platonic or amorphous shapes end up naturally defining, and to a certain degree illustrating, potential relationships between ideas and forms, all while searching and testing concepts.

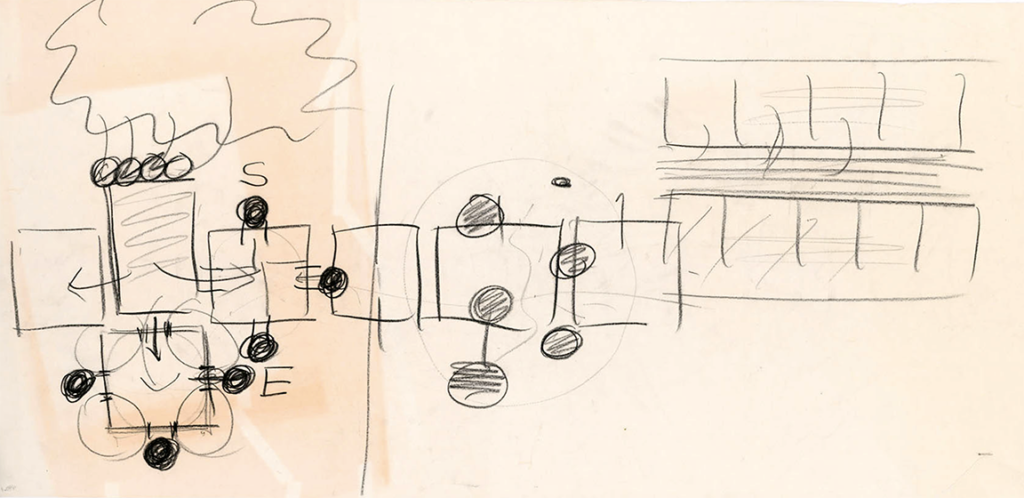

In this process, using shape is unavoidable. Thus, for students, it is imperative to recognize that their first sketches—typically elementary and often rough in their formal definition—are the only way to set thoughts and ideas on paper; a first visual way to conceptualize their design. Sketching is a means to think and work ideas out. It is about defining the problem, and the why and the needs to be solved.

Starting with simple and often incomprehensible scribbles—making a lot of bad and messy decisions is part of any process—sketching sets in place a scaffold supportive of early concepts that, as students mature, build on the capacity to further visually understand AND communicate their thought processes. This initial misunderstanding—that the sketch is the final building—is generally followed by a second challenge.

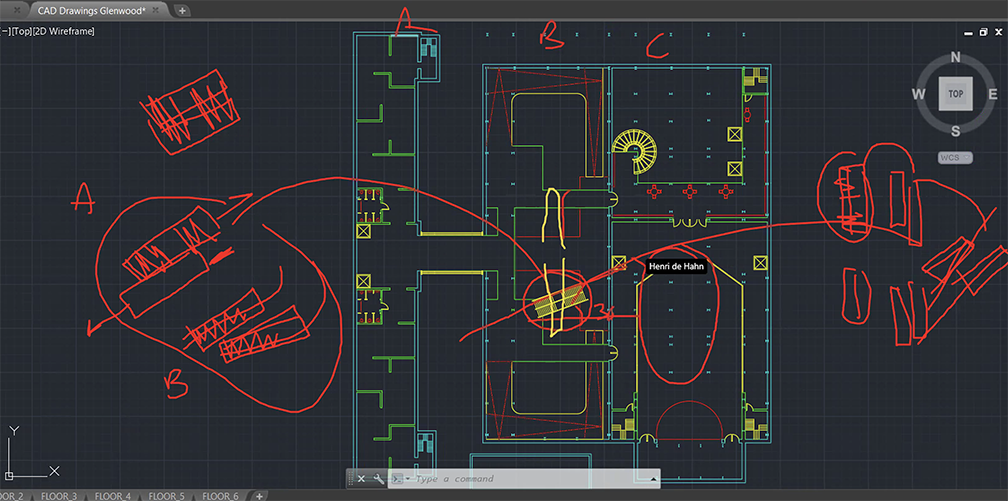

2. My project or their project…

Far too often after robust discussions with a student, confusion arises as to what to do next. When I was a student, I hesitated to build upon drawings produced during desk crits. They seemed to belong to the instructor, especially if drawn by them. Thus, I felt it inappropriate to continue along that path. Now that I am a faculty, I advise students to consider the (my) sketches not only as a testimony of constructive discussions, but I invite them to follow one of two different paths to further their project. Either they can broaden the sketches by transforming them to include their personal interpretation. Or, simply disregard those sketches, but with the understanding that any of their new drawings need to convey ideas of a similar precision of thought.

Both opportunities to further develop their process tends to reassure students that either way they can build on the critique and move to the next level of investigation. When it is understood that sketches made by a faculty remain simply “drawings” that express an interpretative verbal explanation of a student’s project, the question of ownership of those drawings is no longer an issue.

Developing early-on good habits means incorporating the teaching and learning experience, and ultimately, it is the student’s responsibility to own their project during the entire design process. This leads me to the third challenge that seems to always be a major stumbling block.

3. Thinking and sketching, sketching and thinking

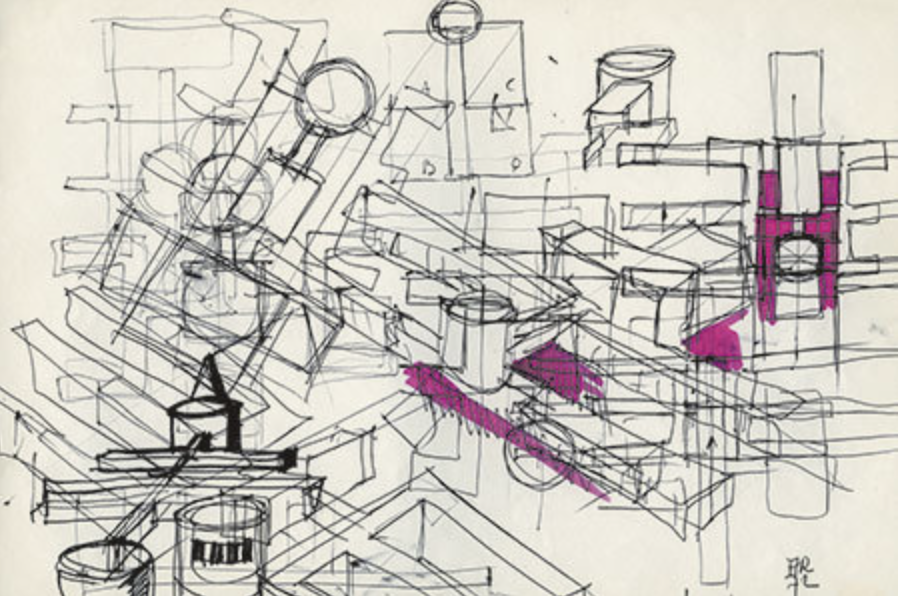

Perhaps thinking and sketching is the most important aspect of an architectural process. As students learn that form suggests ideas and rarely the final shape of a building, and that the richness of drawing is a conversation, they seem to believe to have an insurmountable problem; namely how to think and sketch simultaneously.

As students witness how to work seamlessly between thinking and sketching, and vice versa, for some reason they still retreat to conceptualizing their project in their mind, or worse, to envision a prepackaged set of ideas prior to any scribbling on a piece of paper. I have empathy for this hesitation and initial inability to throw oneself into the lion’s den, but the more a student attempts to engage in this dialogue between thinking and sketching—similar to having both hands speak to each other—the quicker they will advance their project with confidence and take unanticipated and welcome design paths.

I suspect one of the obstacles is that the first sketches rarely look pleasing, and are a poor representation of the idea. Students are unwilling to see that there is always room for improvement. The aesthetics of the sketch should not matter, as the importance of sketching is to evaluate the concept in terms of how well one has translated ideas into space, be that in a sketch or a sketch model. Practicing this back and forth conversation between sketching and thinking always ends up with a process that points towards a more sophisticated and well thought out project. In fact, I would argue that sketches will tell you what they want to become.

Finally, I often invite students to take advantage of what may be understood as a mistake in a drawing. I see how they shy away from their first disappointment at what is one the piece of paper, but here is the magic of inaccuracies. What would happen if two lines that should have been parallel ended up skewed? One can either realign them to meet the initial intention (of course through a new sketch), or take advantage of the error to further the suggestive power offered by the drawing. While sketching, there is little order at the beginning as ideas provoke hundreds of iterations until a structure emerges that tells us that the project now carries a strong idea. It takes time to assimilate, as first instincts are to correct the drawing without seeing the potential of any “mistakes”.

Conclusion

Either way, learning to sketch in these ways is to balance “artistic” intuition with constraints imposed by a program’s brief. To be nimble and trust common sense intuition—which often seems unoriginal for a student who has predetermined the form they want—and take advantage of unseen opportunities, enriches the design process. “Design [sketching] is a practice of ‘letting go,’” and seizing the moment to grasp what is important.

Just give it a try and you will see dexterity, confidence, and self-esteem as a designer grow exponentially.

Additional blogs of interest

Architectural sketching and how do I sketch

The importance of sketching for architects, Part 1

Some thoughts on sketching by hand

Sketching on a field trip, Part 1

Sketching on a field trip, Part 2

Issues about sketching, Part 1

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 2

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 1

Architectural Education: What issues does one encounter when sketching?

Why Model Sketching? Part 5

Why Model Sketching? Part 4

Why Model Sketching? Part 3

Why Model Sketching? Part 2

Why Model Sketching? Part 1