Model Sketching, Part 1. In a digital world, sketching as a process of iteration is too often relegated to the past. Coordinating the mind, hand and pencil was once an activity essential to the education of an architect and remained important in order to represent ideas rapidly and concisely. I teach in an architecture school where we still impart these skills because we collectively believe in the act of sketching as a foundation prior to introducing students to the many 3D Modeling Software programs.

Analog versus digital model making

Using Sketchup, Grasshopper, Rhinoceros or Revit (Building Information modelling (BIM)), enables students to be digitally proficient, a requirement in today’s world. To have students create with contemporary design tools is important, even critical, simply to ease the transition to their professional careers. Digital tools claim to make design thinking, design ideation and design modeling (versus to project) easier and faster, but what about model making in the old way and more importantly the idea of physical model making and model sketching?

I believe that for students in the early years of their degree program, there is nothing more tangible than to craft a three-dimensional mass model, for example, to develop a site strategy. Making is key to this process, and cutting, slicing, adjusting and re-cutting until a sense of coherence develops, is, I believe, only possible with a physical model.

The process is visually intuitive and offers an immediate comprehension into the 3-Dimensional world. At the beginning, this technique may seem frustrating because of the use of clay or chipboard (foam core boards are unsustainable as a material), which tends to restrict the students to basic shapes, however, after discovering how rewarding the outcome is, there is no leaving behind this outmoded skill.

I recognize that some may still favor the digital world where the design of shapes seems instantaneous, but which I believe often lacks an initial depth and a genuine 3D coordination of all aspects of the model. Do not get me wrong, the digital world is here to stay, but with experience, I have come to realize that traditional foundations are essential prior to designing in the virtual world, thus faculty need to let students find a balance and their comfort zone between the analog and the digital.

Rex and OMA

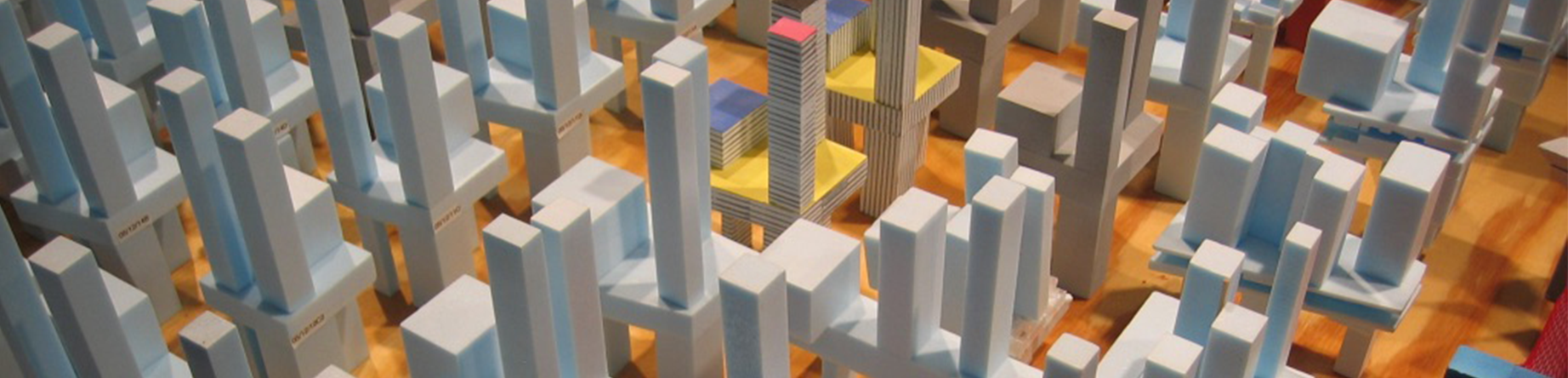

In 2006 I visited a gallery in Louisville, Kentucky where the work of architect Joshua Prince-Ramus (REX) was on exhibition. He is a former protégé of Dutch stararchitect Rem Koolhaas, principle of Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA). REX’s proposal for the Louisville Museum Plaza was reminiscent of many urban moves from his previous partnership with OMA (in fact the project was initially co-authored with them, but ended up with REX after Prince-Ramus’ departure from OMA’s New York office), thus the project and the renderings were not shy in their formal language (Image 1, below).

The project was eccentric, provocative and seemed childishly visionary in its technological references to Russian Constructivism. Yet what I remember vividly was a section of the exhibition that featured hundreds of small mass models neatly aligned like a city grid, showing energy and playfulness in defining the riverfront of Louisville. Some models were reminiscent of a bygone modernist aesthetic, while others where conceptual slippages that were difficult to apprehend. Nevertheless, I was in awe in front of the size of this dazzling rendition, yet never really convinced of its sincerity.

Question of scale for model making

Building on the positive side of this experience, as well as on my own tenure as a faculty and practicing architect, I continue to ask my students when responding to a modest or more ambitious design project to develop a number of “to scale” mass models that show a basic principle of settlement through shapes and volumes, but most importantly demonstrate how to define relationships between the building and the site. The purpose of these sketch models (or mass modeling) is simple: to read and understand the site, interpret the brief, and propose a site strategy that is elegant and makes sense.

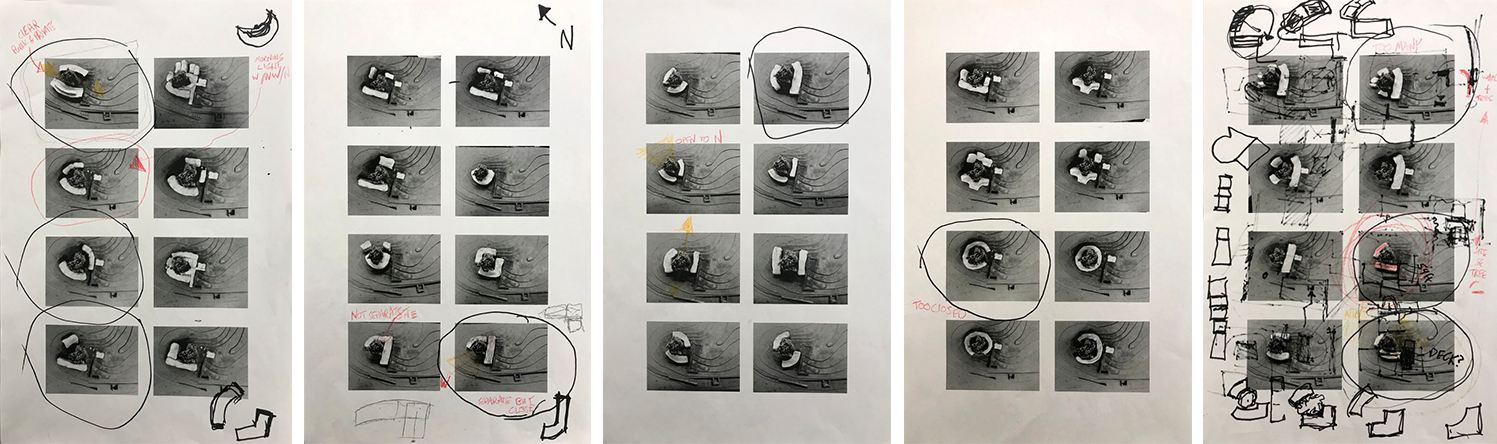

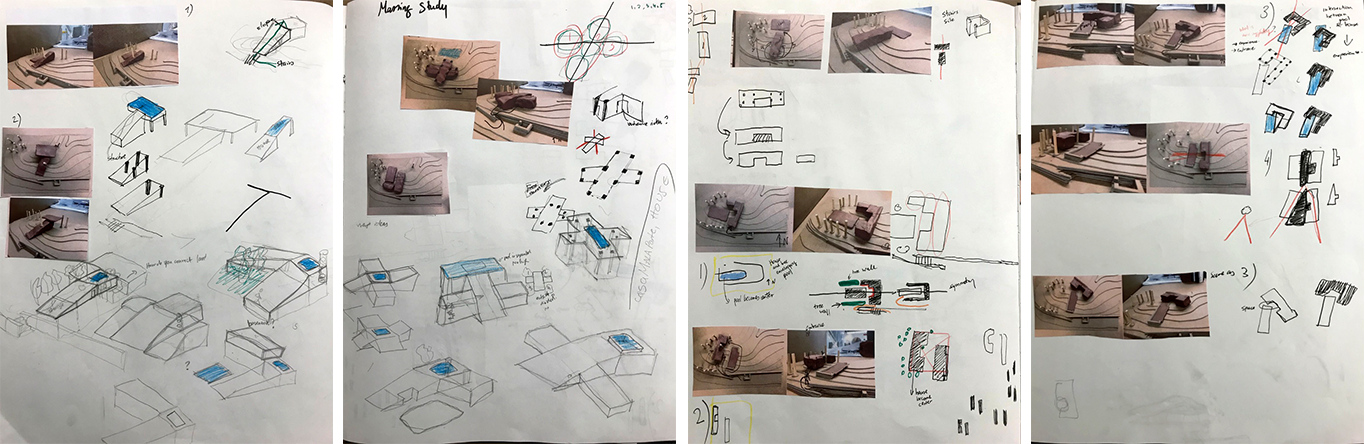

Like REX’s obsessiveness, many of my students dived into creating model after model, testing ideas about possible site integrations as either a seamless continuity between the architecture and the site, or at times, by expressing a refusal to engage the immediate context. The photographs taken from student sketchbooks (11”x14” please!) show how two of them expanded on the straightforwardness of the assignment.

Example 1

In the first example (Image 3), the five images show 40 mass models leading to a site strategy where the existing and sole tree on the site is celebrated as a central feature of the scheme. Orchestrating the images in his sketchbook, a second narrative took place through a visual layering of conceptual adjustments to draw out key principles.

A messy proposal ranging (Image 4) from drawing circles (indicating similar conceptual strategies), contrasting an open or closed parti (a French Beaux Arts term signifying an organization in plan based on required functions), to proposing conceptual diagrams layered over the actual photographs. A process that is rich and intuitive, which translates the student’s personal and expressive manner of designing.

Example 2

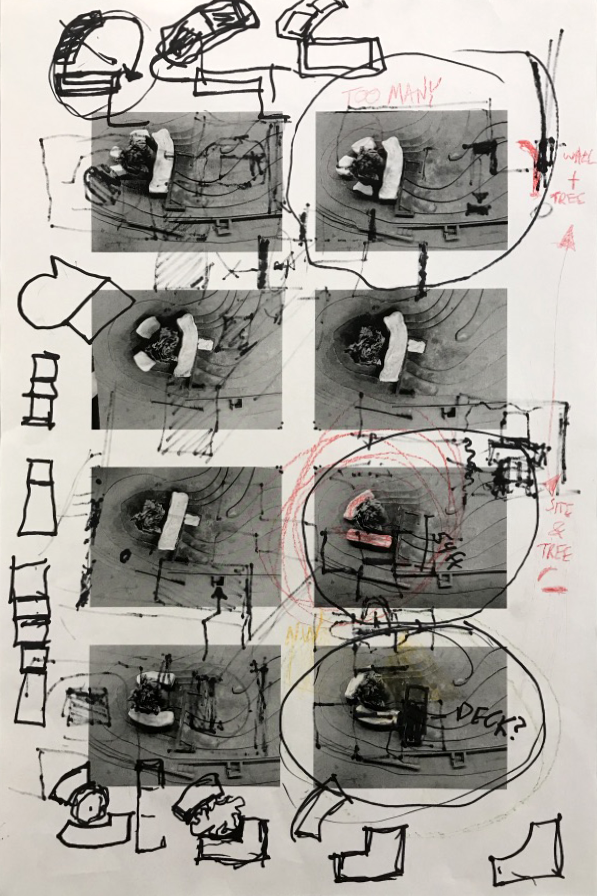

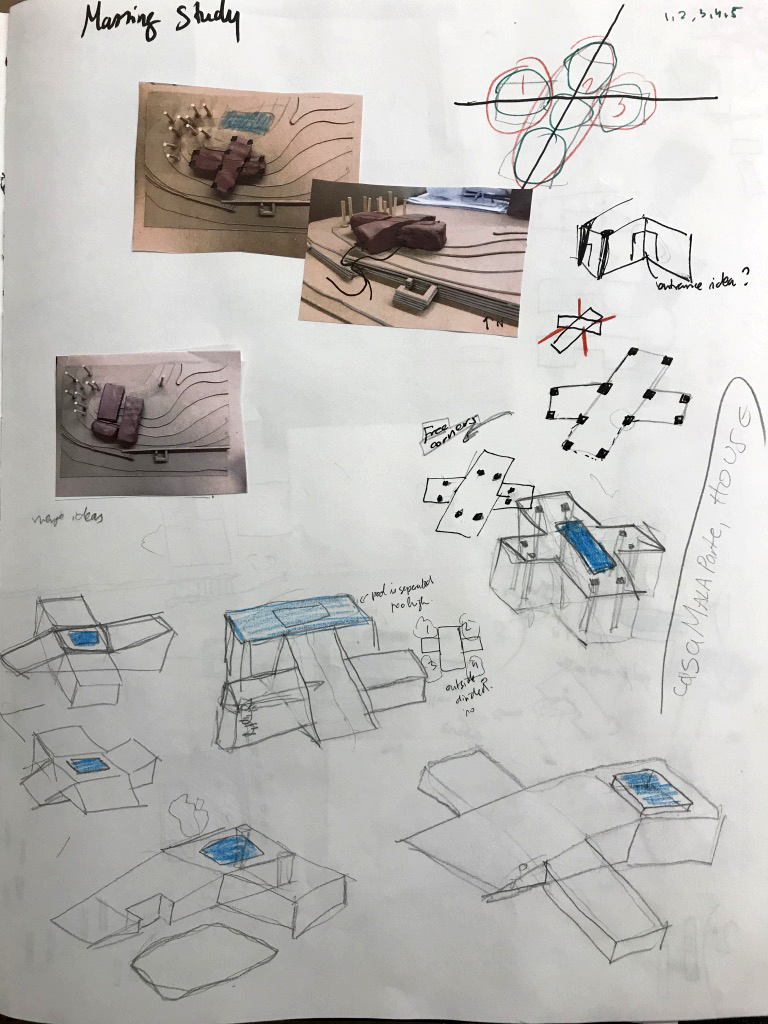

The second student’s process (below) is similar to the first example. While less logical in the systemic organization of the images, which are often accompanied by random framing, she uses the remaining white page to further develop through axonometric drawings, the “objecthood” of the overall massing of the building.

Working at times in a transparent manner, her investigation expands beyond the simple site massing to incorporate structure, circulation and the complexity of volumetric intersections based on various functional requirements. The use of colors, notations of axis and shading clarifies important concepts beyond the simple massing on the site.

Conclusion

While this method suggests that mass models should be done at the beginning of a project, students learn that mass models can – and should – continue to influence them throughout the design process. At any moment, this technique can offer further reflection on how to proceed.

Postscript

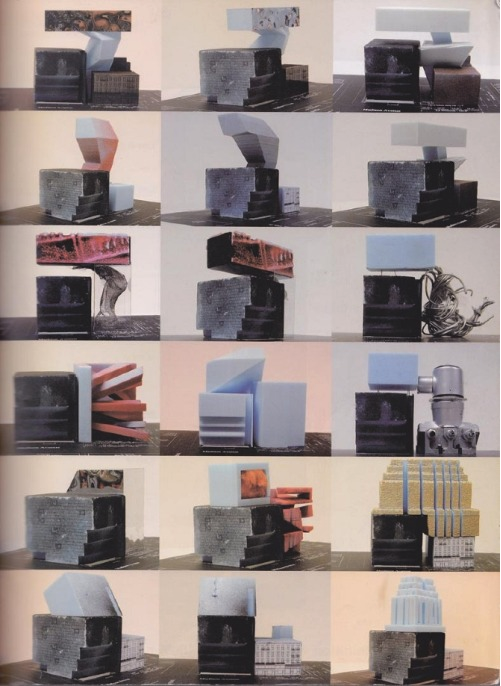

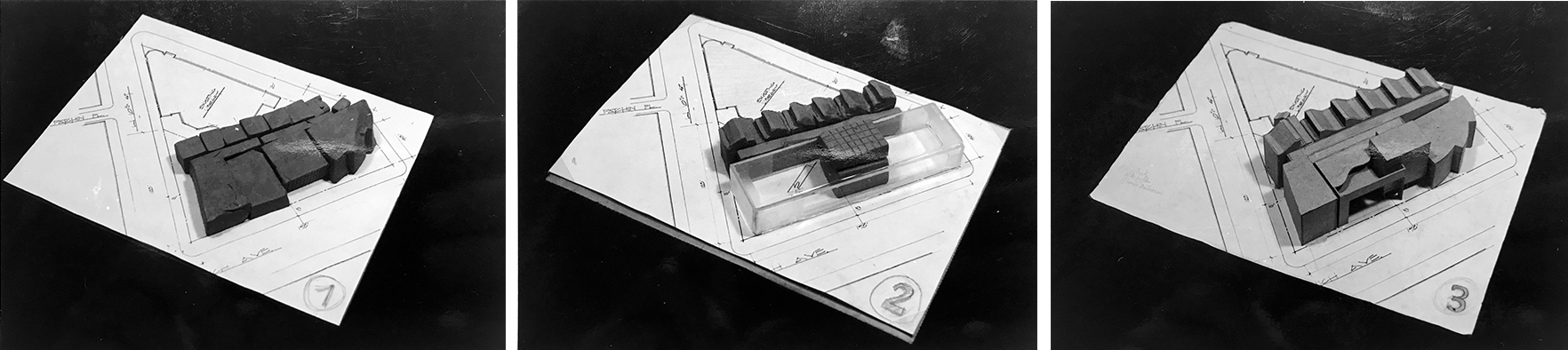

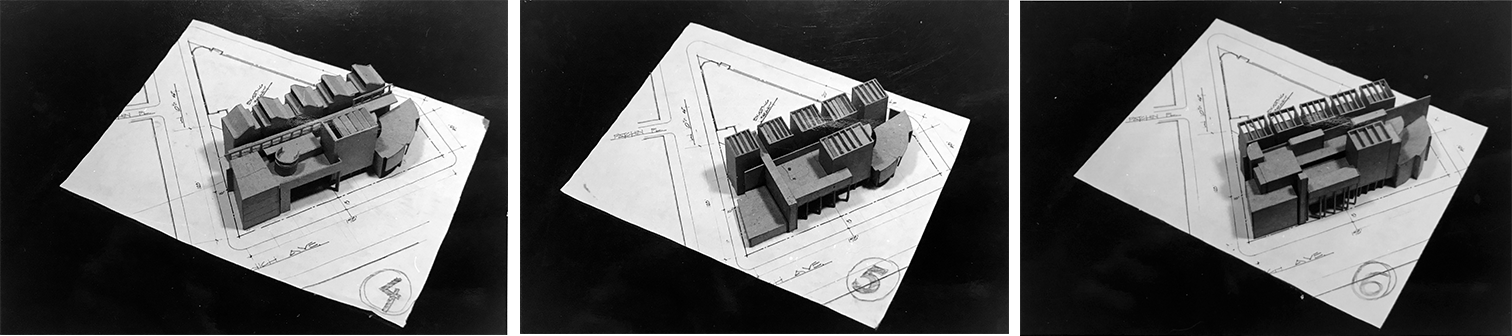

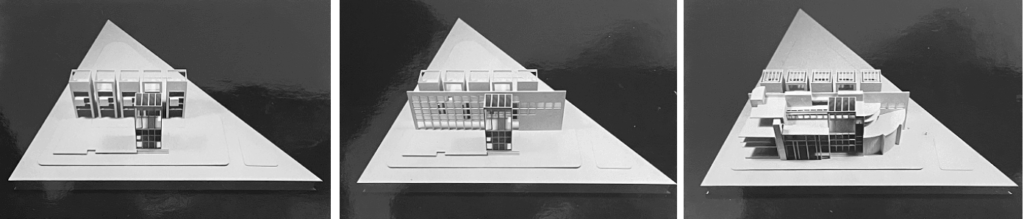

I’ve included a few images of mass models at two scales (scale 1/32″=1’0″ and scale 1/16″=1’0″) that I developed as a student. The project was to design a high school in the West Village on a triangular site at the intersection of Greenwich Ave, West 10th Street, and 6th Avenue in New York City. The progress models shows basic massing, the conceptual idea of a building, leading to the elaboration of more sophisticated tectonics. The first six images are done in clay and in chipboard where you can see the elements of permanence get stronger with each iteration (Image 7).

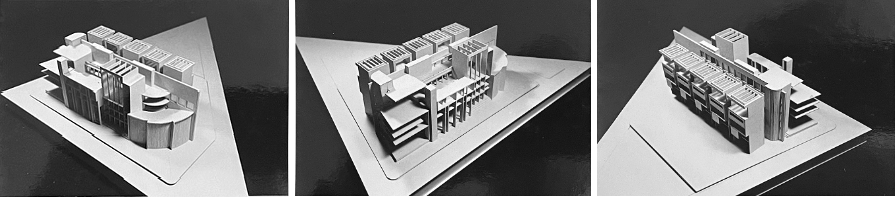

Final model at scale 1/16″=1’0 shows more intricate detailing of the overall functional distributions and programatic idea (Image 8 and 9).

Additional blogs of interest

Architectural sketching and how do I sketch

The importance of sketching for architects, Part 1

Some thoughts on sketching by hand

Sketching on a field trip, Part 1

Sketching on a field trip, Part 2

Issues about sketching, Part 1

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 2

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 1

Architectural Education: What issues does one encounter when sketching?

Why Model Sketching? Part 5

Why Model Sketching? Part 4

Why Model Sketching? Part 3

Why Model Sketching? Part 2

Why Model Sketching? Part 1