Architecture techniques. As an architect, I have always cherished designing a project. Over the years, I’ve come to understand that making a project is more about projecting a model of life than designing, which comes from the Italian designare, meaning to draw.

This belief holds true when I teach architecture, where too often project and design are seen by students as equivalent; a confusion that I believe undermines the true vocation of the work of an architect. And yet, both terms project and design—or to project and to design—work in tandem when dealing with any design process or with any techniques; the latter being the topic of this blog.

Techniques

Beyond the importance of using correct tools (i.e., understanding which pencil lead to use, applying the correct hand pressure to draw crisp, clean, precise lines), is the acquisition of fundamental techniques. Learning techniques is important for any student, and should be the start of becoming a life-long learner. In this blog, the term technique is defined as “the practical aspects of a given art…” while “skill [is the] capacity to do something well.” Both are usually acquired and/or learned through the practice of a project.

Within academia, mastering certain techniques must become second nature for students if they want to understand how to move their projects forward. Over my years teaching, I have observed that learning basic techniques early-on is essential because it complements the acquisition of fundamental design skills and allows students to acquire good habits, while also moving confidently from an early conceptual idea to sophisticated deliverables, typically required for final reviews.

The question I had as a student—beyond my early struggle to find inspiration to create space—was how to gain the necessary confidence to rely on a solid design process. Happily, my teachers offered us an education that not only focused on the design of a project, but as importantly, on the question of how to design a project. Two very different beasts necessary to achieve excellence.

Seminars

At my alma mater, the EPF-Lausanne, a bi-monthly seminar was dedicated to the ‘act of projecting’ and the subject matter was integral in learning how to create space. As a young student, I remember these roundtable sessions as eye opening. They were part of the design studio; not simply as a visual Grand Tour excursion, but as a forum for discussing, for example, the fundamental difference between a column and a wall in the work of Louis I. Kahn.

This duality might seem at first uncanny—how the intuitive aspect needed to create space (doing a project) is balanced by a rational process to make the project happen (the act of projecting)—but for students, the struggle in their project is the inability to grasp which steps might bring their design forward. They are looking for inspiration, when they could turn to techniques as a tool. Success is about our ability to learn from failure, but more importantly, it is the ability to rely on basic techniques that with time are understood and honed as they are integrated in a design process.

When to use techniques

When I talk about process, I have noticed—perhaps at an increasingly alarming rate due to an Instagram culture—that during the early stage of a student’s design, there is an overt reliance on preconceived ideas and the instantaneous production of images (i.e., the sketched geometry often representing the final form of a building). To offset those inexperienced assumptions, all the while advancing the student’s ideas, one needs to talk about the design process.

Yet, in doing so, I realize that students often do not know how to proceed to the next step of their project, because they have not been introduced, or have not fully mastered various design techniques. Also, and perhaps most importantly, when a technique is introduced and later explored as a design tool, students tend to believe that the technique can only be used at a particular juncture of the project, often mimicking the moment when the technique was first explored.

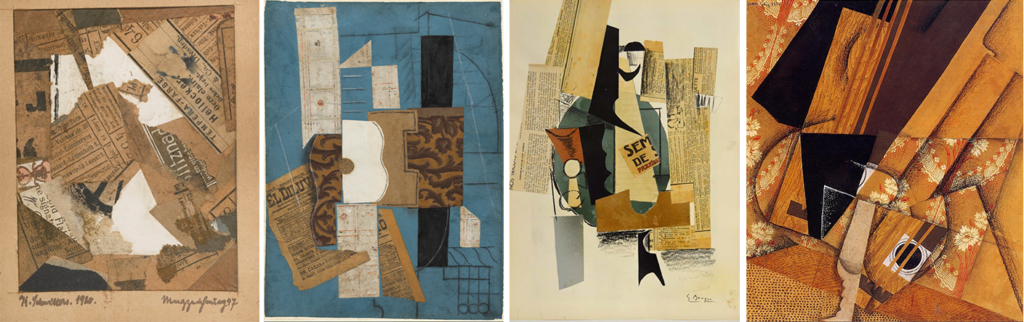

I remember being introduced during my studies to the richness of Dadaist and cubist papier–collé; a technique called collage where paper and other two-dimensional components are adhered to a flat surface. Robert Slutzky let us discover how with their formal richness, collages create new meaning. As students we assumed that use of this new technique had to unfold at a precise moment within the design process.

This was perhaps because he introduced the concept at a particular moment during the semester. Our confusion persisted for some time despite Slutzky’s strong suggestion that collage could be an impetus to create a conceptual idea or be used later in the project—often with the removal of functional constraints—to investigate relationships of form and geometry. I am referring here to collages by architects Richard Meier and Bernard Hoesli.

Excursion: Cooking techniques

I have come to appreciate the significance of techniques in my art form, and understand that mastering them is an essential component to the success of any architectural project. I often compare their acquisition to techniques found in the culinary world. Not only because like most architects I enjoy cooking, balancing the rigorous and intuitive aspects of transforming and presenting food, but because cooking requires rigorous basic techniques. However, I will admit that I am a terrible baker as I like to improvise and fail to adhere to exact proportions between baking powder and baking soda!

Mirepoix

For example, knowing how to slice, chop, dice, or mince vegetables is essential when cooking. It is equally important to know how to use these transformed ingredients appropriately; what heat they need to be cooked over, and which fat is necessary. Case in point, savory dishes such as soups and broths, rely on sautéing diced vegetables and remain the staples of many dishes.

In France, this staple is called mirepoix and uses onions, carrots, and celery. Many other cultures adapt similar vegetables with local additions: battuto and soffrito (Italy); suppengrün (Germany); soffritto (Spain); recaito (Puerto Rico); wloszczyzna (Poland); Ahogado (Bolivia); or the Cajun Holy Trinity in the United States. Without the staples and fundamental techniques of mincing and cooking the vegetables, many dishes would fail to exhibit the indigenous flavors that we have come to savor and which constitute such a wide variety of dishes.

Over the years, I have come to understand the importance of selecting which pan (material, size, depth) is necessary to create the perfect dish. Needless to say, making the right choice results in mastering staple techniques such as sautéing, searing, browning, deep and pan-frying, roasting, barbecuing, steaming, simmering, stewing, sweating, blanching, poaching, and tempering. Yes, those are fundamentals as much as the more mundane act of building up a stock. Excellence in cooking is about understanding techniques developed by and adapted to various cultures.

All of these techniques act as the backbone of a chef’s repertoire, thus, in my analogy between architecture and cooking, I see strong similarities between the need to master techniques in the kitchen and in the architecture studio.

Let us return to architecture…

The virtue of most techniques is that, if well executed, they should disappear, subsumed to the larger goal and flashier aspects of the project; namely, the creation of a meaningful space, the expression of beauty and strong tectonics, all the while constantly searching for a more equitable model of life.

In this design spirit, I created a number of blogs (see below) that touched specifically upon techniques of sketching and sketch models. The inspiration of today’s blog is that I am always pleased when students command design skills while also inventing upon established techniques.

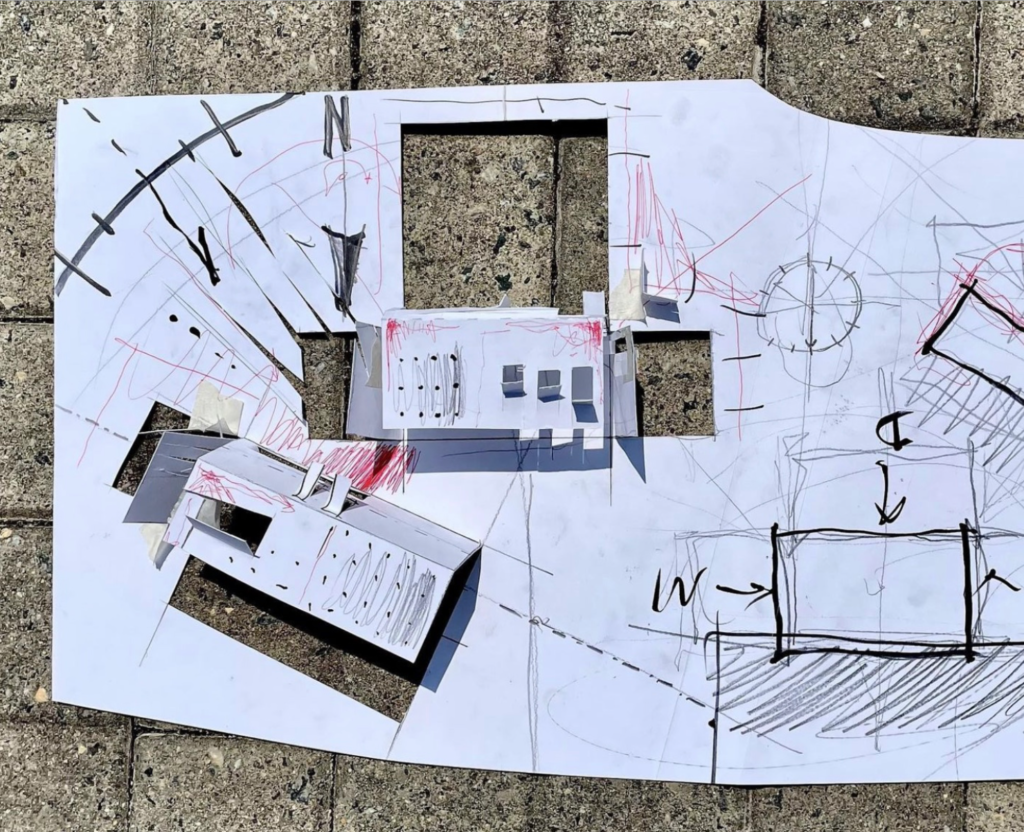

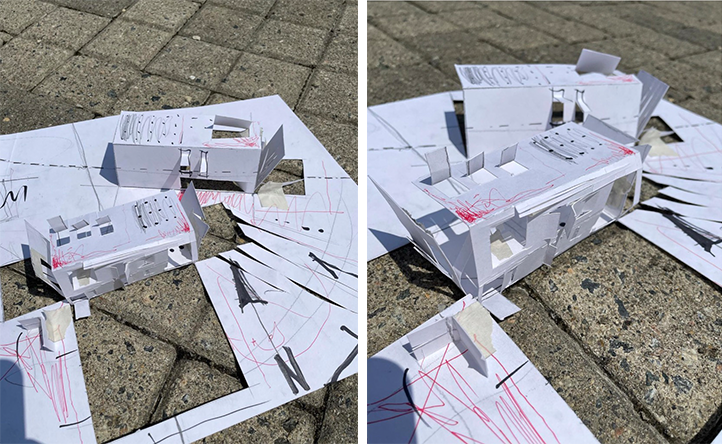

Case in point, when a former student of mine shared his winning competition entry, I realized that by combining several techniques such as sketching and model sketching, he was able to investigate his ideas simultaneously in both forms. Sketching on a large Bristol board in a variety of mediums, then cutting and folding that same board to create enclosure became, in his hands, a new technique.

My dream as a faculty is to witness a student hone their choice of the right techniques at the right time to express ideas during their design process. But when a student combines techniques learned in class to create a personal technique, it makes teaching even more rewarding.

The importance of sketching for architects, Part 1

Some thoughts on sketching by hand

Sketching on a field trip, Part 1

Sketching on a field trip, Part 2

Issues about sketching, Part 1

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 2

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 1

Why Model Sketching? Part 5

Why Model Sketching? Part 4

Why Model Sketching? Part 3

Why Model Sketching? Part 2

Why Model Sketching? Part 1