About sketching -an iterative process, Part 2. I believe that for any design process to be successful, there is a need for iterative sketching to accompany the production and testing of architectural ideas. To be able to compare and contrast between sketches is critical and allows decisions to be measured on the strength and legitimacy of one’s conceptual ideas.

For the designer, this method of investigation comes in many shapes and forms. For students, sketching may not come naturally at first, and only with much practice does the skill become second nature. For me, when working on projects or teaching students, I favor two simple sketching methods. They are not unique, but understanding the merit of each may help the students clarify their early approach to the design process.

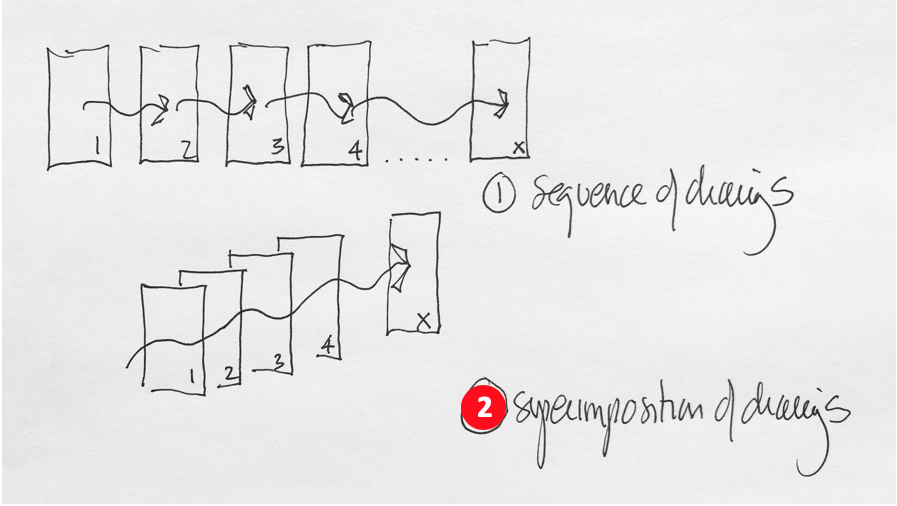

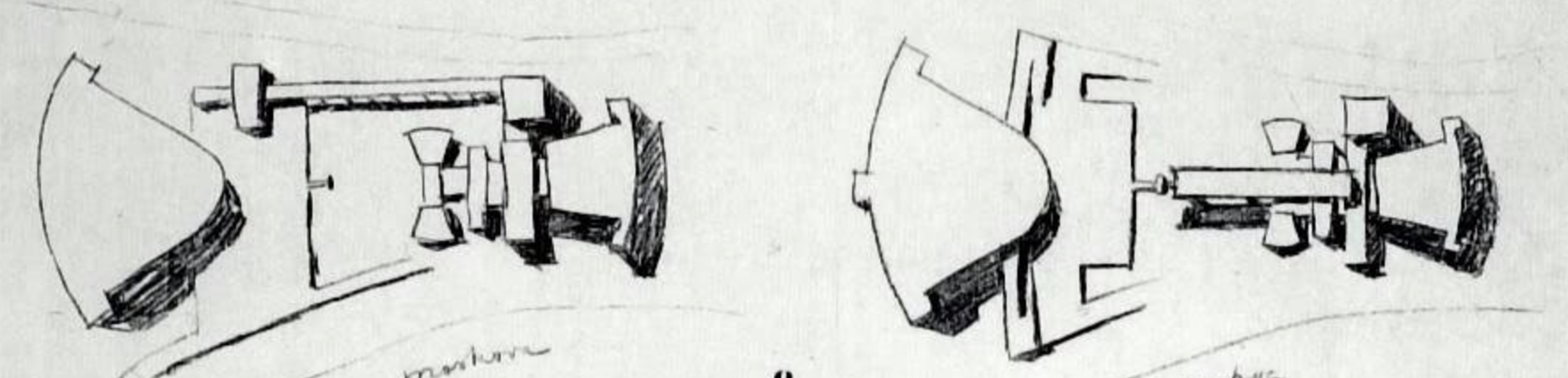

Image 1: Google images -Sketches by Le Corbusier for the Palace of the Soviets, Moscow, Russia, 1928-1931Image 2: Google Images -Photograph of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret studying the model for their competition entry of the Palace of the Soviets

The first method

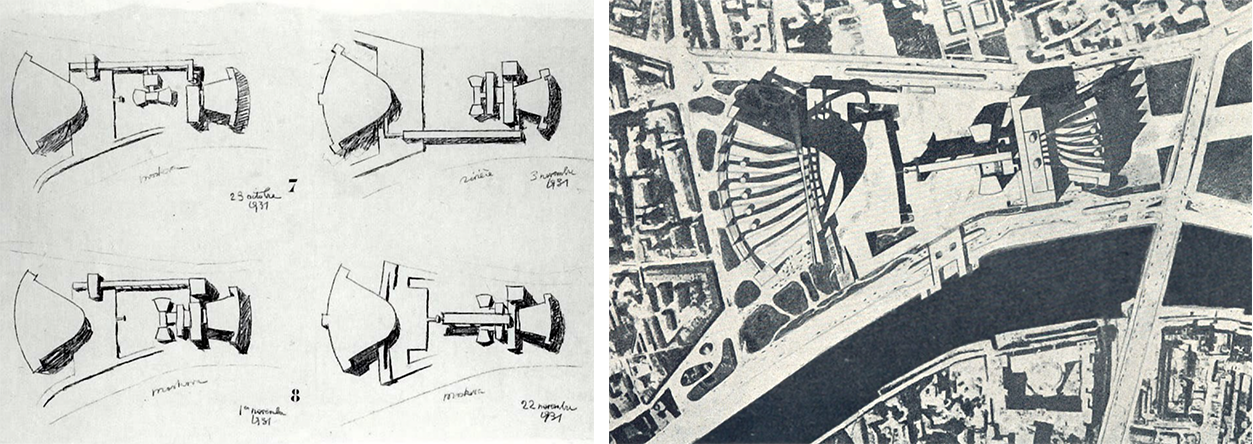

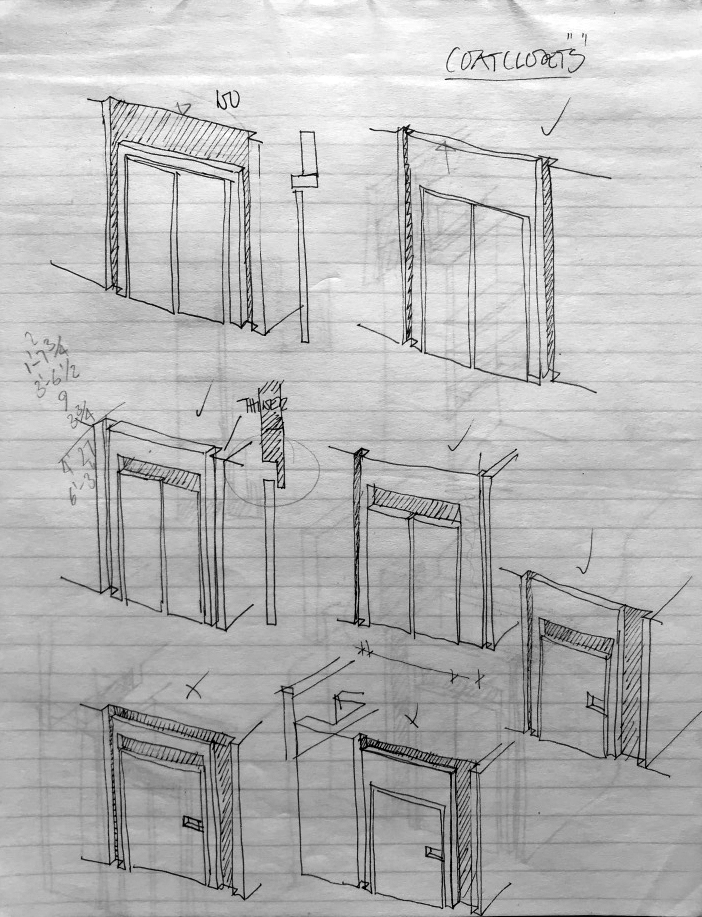

The first sketching method develops a sequence of drawings (Image 1 below) that produce and test ideas. Working in a staccato fashion (from the Italian musical term meaning a “detached” note of “shortened duration”) each sketch is drawn separately in a clear and succinct manner. Drawings may express disconnected thoughts or a progression of a single idea. This is important as it allows two ways of understanding progress. On the one hand, each sketch leads to another sketch and is seen as a testing ground of different ideas or concepts.

Image 3: Sketch 1 showing a process of sequencing drawings (author’s collection)

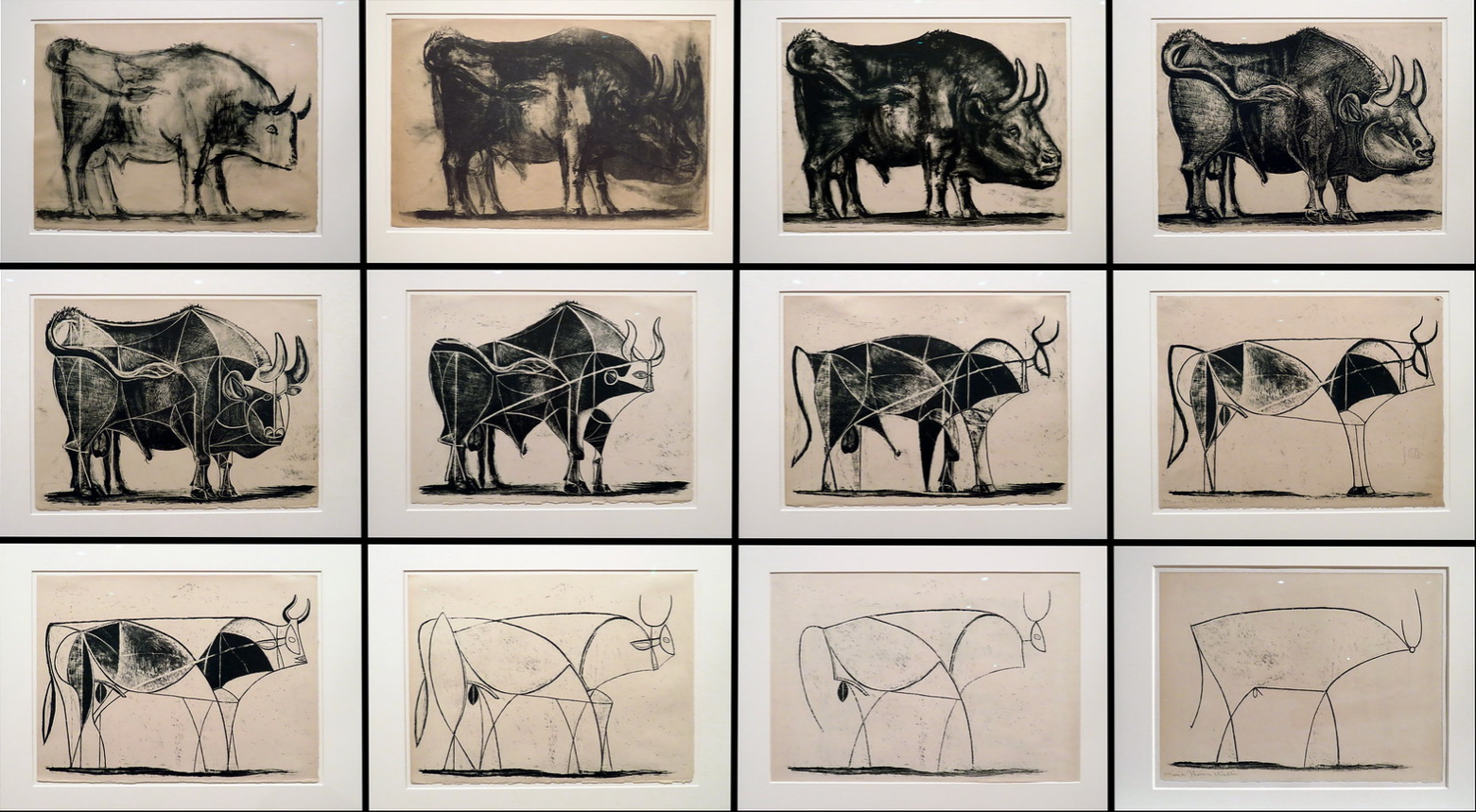

Alternatively, one may read each sketch as part of a continuity that expresses slight adjustments and refinements to a single idea. Either way, each sketch encapsulates the reality of a particular moment in time, and, if correctly done –meaning sketched rapidly and loosely with a certain degree of precision– should convey the intention of the idea with fervor and strength. The above example, shows (to the left) four diagrams by Swiss architect Le Corbusier. The project is the 1931 competition entry for The Palace of the Soviets in Moscow, USSR. The fifth diagram (Image 1 above, to the right) is part of the final submission proposal.Image 4: Google images -twelve plates showing Pablo Picasso’s exploratory process

Also, to see each sketch as an independent drawing in close proximity to the others (both conceptually and physically), allows the eyes and mind to evaluate the progress from one sketch to another. In other words, one can at once judge and assess slight differences or major changes between drawings. Finally, in this process, there is no need to work at scale, yet, I believe that scale is not simply about working at a particular scale (i.e., 1/16=1’-0”) but understanding scale as a system of interrelated proportions that convey appropriate relations among each design component.

Neither is there any necessity to seek beauty in the drawing. Its visual and perhaps aesthetic validity will emerge as being faithful to the testing of idea(s) and its success will depend on the practice of coordinating the mind, hand and drawing. The above twelve images titled “Bull” are lithographs by Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), created around Christmas of 1945. The beauty of these iterative sketches moves from the academic to an abstract iconography, and illustrate Picasso’s search to “find the absolute ‘spirit’ of the beast.” Both Le Corbusier’s and Picasso’s examples show different iterative ways of sketching ideas within this first method.

Image 5: Iterative sketches for a piece of built-in cabinetwork for private client (author’s drawings). Added 01.25.2021

The second method

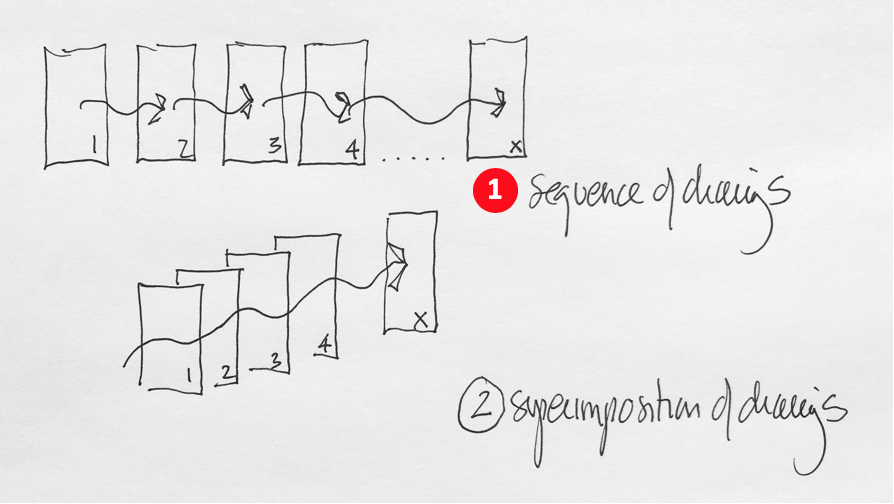

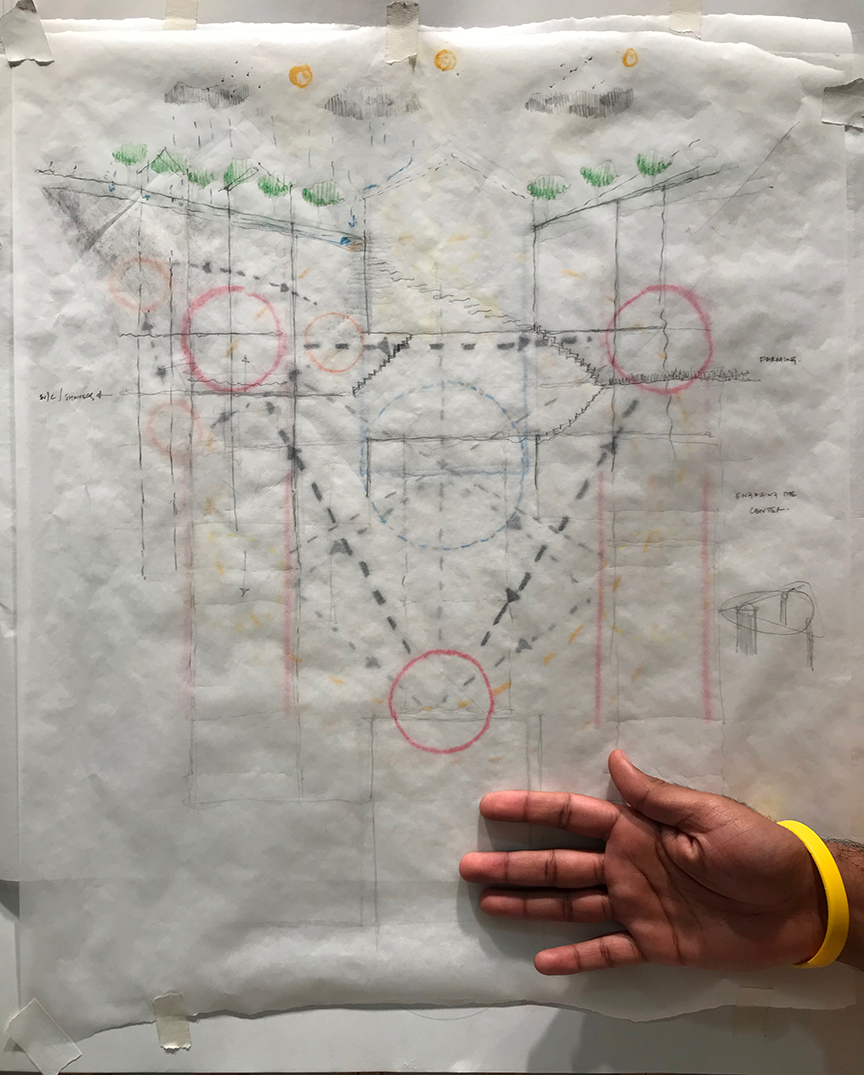

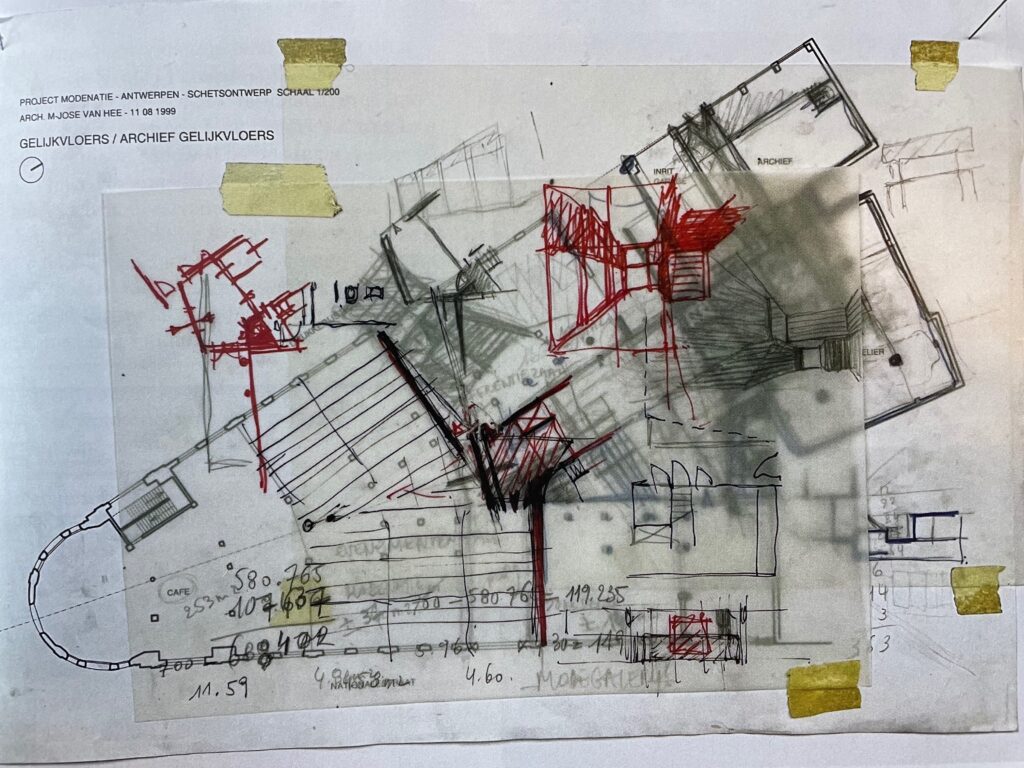

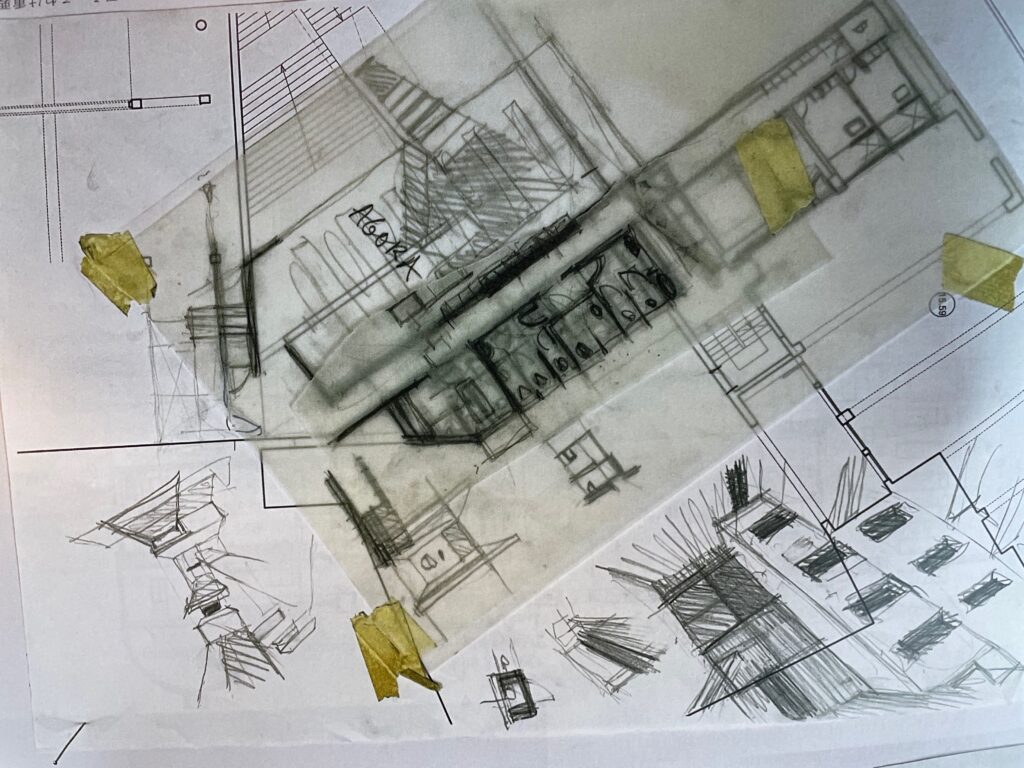

The second method is similar to the above description to the exception that the process of investigation is done by superimposition (below sketch number 2 and student drawing).Image 6″ Sketch 2 showing a process of superimposition

Working in the manner of a palimpsest, sketches are drawn over previous sketches -either directly over an original drawing or by using a transparent tracing paper to keep track of each new iteration, but always keeping in mind that each sketch is directly drawn over the previous one. The power of this second method is more about refining an idea rather than an exploration of multiple ideas, yet both are rarely in opposition and may be used simultaneously in the design process.

Here, the strength lies in the designer’s ability to visually recall certain elements of the previous sketch (assuming that these selected elements have emerged as somewhat important in their need for permanence in the design process), all while making changes on the new sketch which is drawn on a new layer.

Image 7: Student thesis drawing showing his research method through a process of superimposition

This is achieved by a simultaneous reading of multiple layers that creates visual depth to the process of sketching. Similar to a microscope, it is important that when one draws with this method, one trains the eyes to choose and identify what one wishes to focus on. Each layer may contain several important or lesser ideas, yet the richness of this method is to bring together key concepts from each separate layer so that the final sketch reflects an informed set of choices developed by the author’s ability to interpret all of the layers highlighting the chosen information.

As the students practice this sketching method, they will enhance their personal technique of representing ideas through the usage of various lead, color pencils, line thicknesses and other tools. This will allow them to highlight important ideas which might otherwise get lost through the process of superimposition of sketch paper upon sketch paper. Finally, it is important to note that this process cannot go ad infinitum (without end or limit), simply because the readability through too many layers will become impossible to manage visually, thus losing the notion of a palimpsest.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I suggest that in both methods students need to be mindful that the choice of sketching tools will affect the drawing, its readability and success, and most importantly the way in which they investigate and express a conceptual strategy; something that may be the ultimate goal in both of these sketching methods.

Additional blogs of interest

Architectural sketching and how do I sketch

The importance of sketching for architects, Part 1

Some thoughts on sketching by hand

Sketching on a field trip, Part 1

Sketching on a field trip, Part 2

Issues about sketching, Part 1

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 2

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 1

Architectural Education: What issues does one encounter when sketching?

Why Model Sketching? Part 5

Why Model Sketching? Part 4

Why Model Sketching? Part 3

Why Model Sketching? Part 2

Why Model Sketching? Part 1