“…nothing can be more abstract, more unreal, than what we actually see.”

Italian painter, Giorgio Morandi

In previous blogs, I have written about the necessity of skill building to facilitate students to use techniques as a process to diagram conceptually; work through iterative design processes; move from sketch to drafted sketch; and also to learn to sketch in model form.

As to sketching digitally, this is another beast in its own right which I will address in an upcoming blog. There are certainly benefits, ones I truly appreciate after a year of online student learning using various audio and web conferencing platforms.

Field trip sketching

I have also addressed in a blog the importance of sketching during a field trip, a moment in a student’s life where recording what one observes differs from documenting what one sees. While there are multiple points of view about how to mentor students to sketch during a field trip, today I want to add to my earlier thoughts and explore a cinematographic way of recording this experiential journey using the pretext of walking through a city.

For many architecture students, sketching on site relies on recording impressions of a particular building, typically one that was assigned by the faculty as a point of interest to study. Those sketches usually range from depicting the building’s exterior as a memento of the first impression, or interior spaces that caught the student’s attention (e.g., rooms, stairs, light). These sketches use perspective or axonometric—often with bravado, however, may I say, rarely with extraordinary drawing skill.

This lack of skill is, in my opinion, because most students no longer know how to sketch as they favor digital formats as a compelling and immediate design tool—perhaps because it seems easier and the product seems already final. The art of crafting a drawing through diagraming, sketching, or drafting is in danger of becoming a lost art. Perhaps this is because as faculty we no longer insist on quality and a intellectual precision of thought in drawings, qualities that are essential even in rapid sketching.

Most often, both postures (sketching the exterior or an interior moment) take place prior to having experienced the entire building. Trust me, this is more the rule than the exception. It is understandable that students rush in, wanting to make a beautiful drawing as soon as they see a picture worth a thousand words. But what purpose is this ambition if the act of being on site does not entice them to record something that cannot be understood beyond what they see—e.g., the mundane image easily taken with a cell phone? Or even the image readily available on someone else’s Instagram account. Their time on site would be better spent on conceptual drawings, using thoughtful and precise rapid sketching techniques.

An urban sketching experience

I realize that sketching should never solely be about understanding a particular aspect of a building. What I mean by this is that during field trips, students typically move between assigned sites without much thought to what happens during their journey from one place to another. For many students the space between assigned buildings or places seems inconsequential. Strolling, or using motorized mediums to move through a cityscape or landscape is either used to chat about their prior visit, refine a recent drawing, grab a snack, or, to my disappointment, take selfies in front of international brand stores, promptly followed by a text or Instagram post.

Venice, Italy

Years ago, when teaching in Venice, Italy, I asked myself how to get the students to better appreciate the cultural environment surrounding much-admired artifacts. While Venice had at that time few contemporary interventions to visit—beyond the hidden gems of Carlo Scarpa and other singular interventions—there were endless majestic monuments on a must-see list. Thus, to balance the exceptional with perhaps something more mundane during our four months there, I avoided giving the students specific assignments such as the recording of urban pieces like pavement, facades, door entries, door knobs, etc.—even if the uncovering of such little marvels would bring surprise, delight, and astonishment at a smaller scale and be a source of invention for their design projects (Image 3, above).

I was seeking a haptic urban experience based on touch and movement that students could record while walking the intricate and often convoluted streets of Venice. Something more universal and autobiographical that could become integral to their daily experience of the morphology of the city. In short, I wanted them to observe everything, and not merely focus on the objects on their ‘assignment list’.

An urban promenade

When I launched this exercise, I called it an urban promenade. The intention was to offer students impromptu discoveries as a way to read, experience, and document their journey in the city using rapid sketching techniques. My motivation resulted from walking the many calles (streets) that were so familiar to me in daylight and at night, yet I still did not know precisely what made each corner and bit of pavement so memorable. Perhaps as an architect, visual memory becomes instinctive; countless times I would simply turn a corner to proceed to the next ‘marker’ along my journey without any forethought about why I did it.

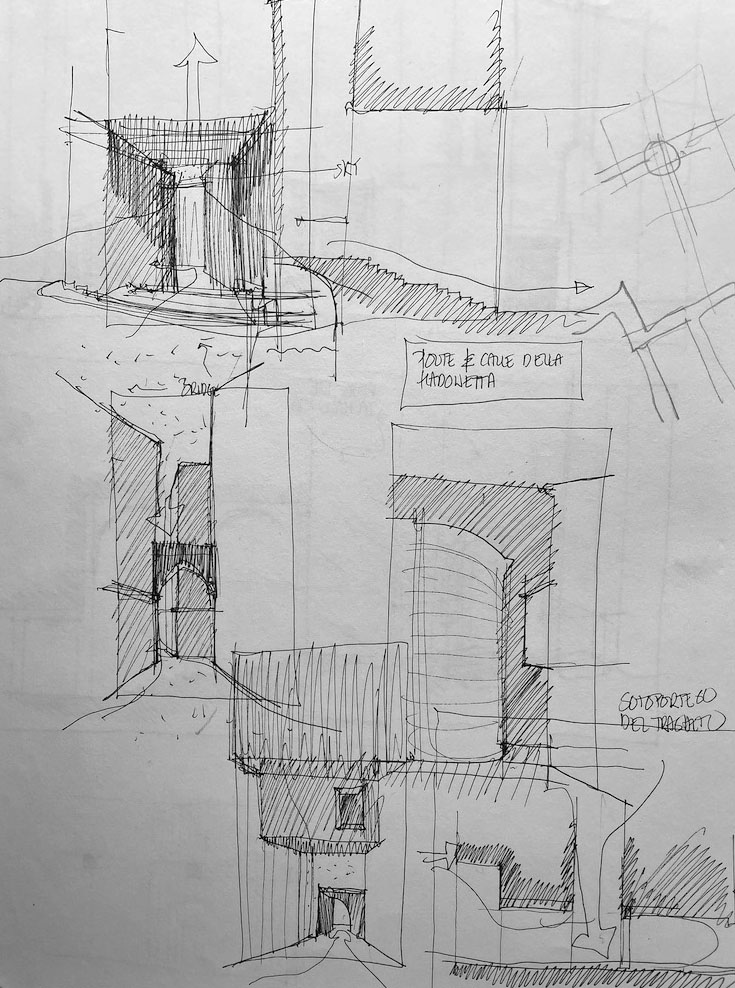

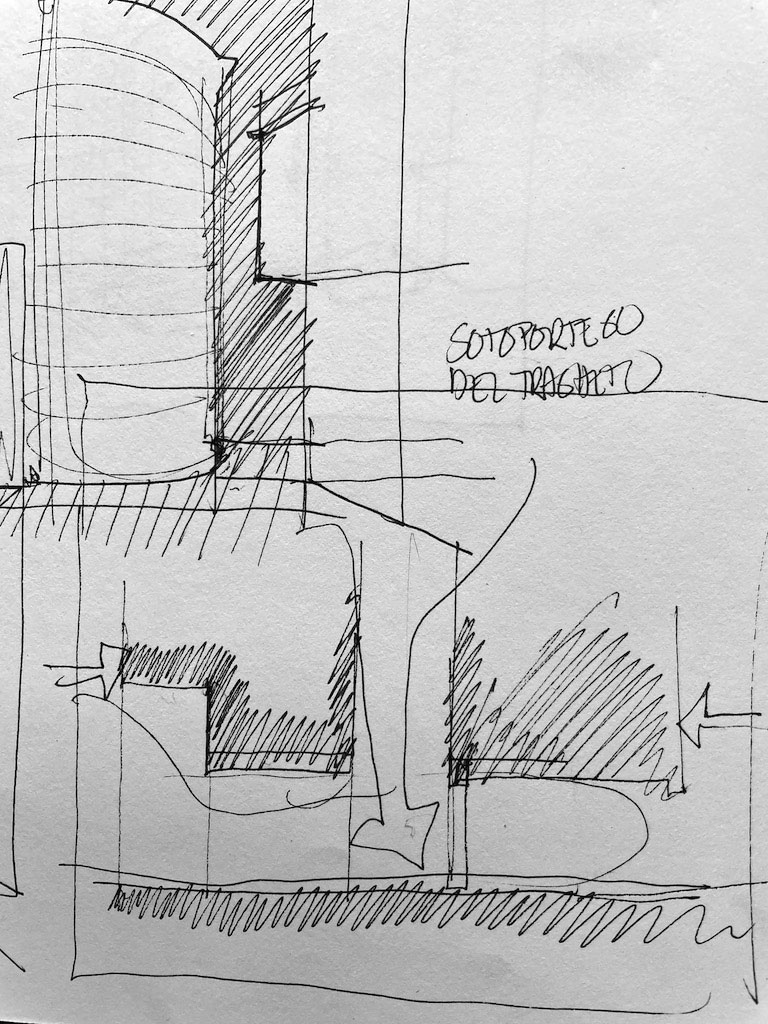

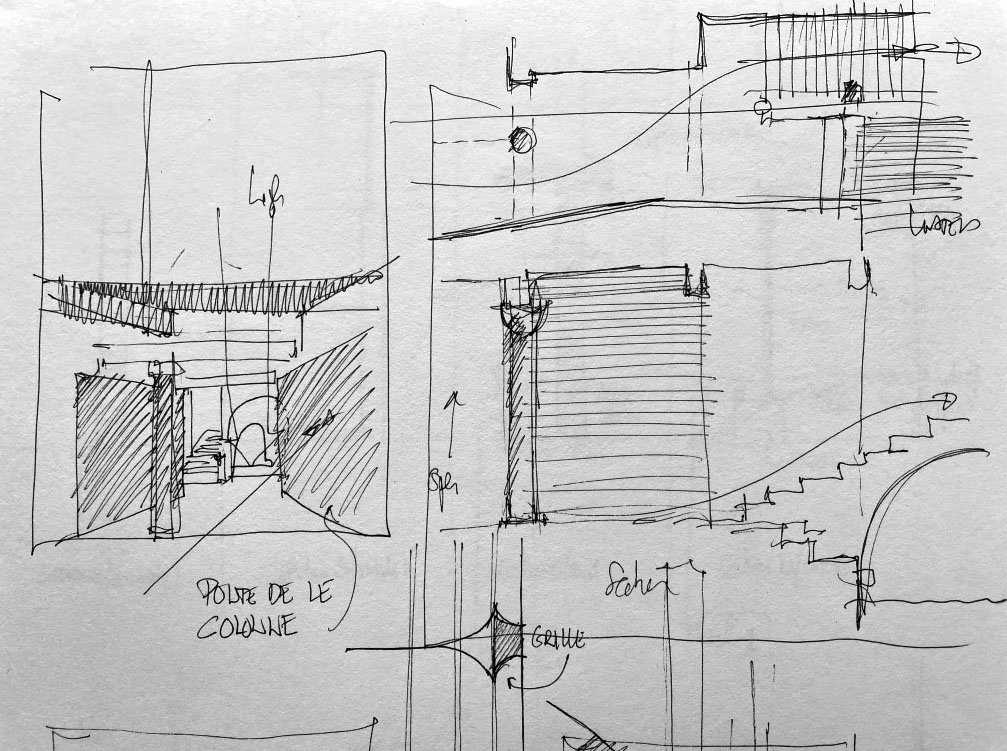

One day, curious about my intuitive way of moving through Venice, I took it upon myself to record a series of urban moments that reflected my journey from place to place. In a certain way, I was revisiting the perceptual form of places as written about in The Image of the City by Kevin Lynch. I did not need a map to get around the medieval and scenographical labyrinth that is Venice, something spatial was already sublimely recorded in my mind. I seemed to own each compression, expansion, Sottoportego (alley that passes underneath a building), and bridges along my habitual promenade. Buildings seemed to bend to create characters in the foreground and background (Image 7, below), while accelerating my path leading under a building and towards another abrupt or awkward turn.

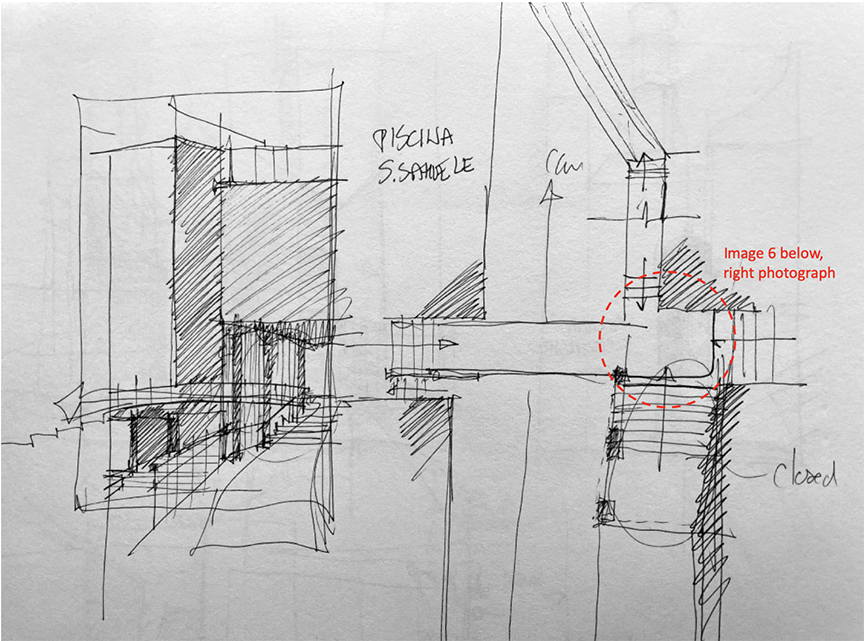

It is known that in Venice when you ask for directions, a true Venetian will always respond Andate sempre dritto (always proceed straight ahead), an oxymoron for anyone who understands the morphology of Venice. The city on the Laguna rarely has straight streets, thus the pedestrian path is constantly negotiated between sharp turns and incongruous multidirectional intersections most often occurring before passing over a bridge (Image 5, and 6 middle and right photographs).

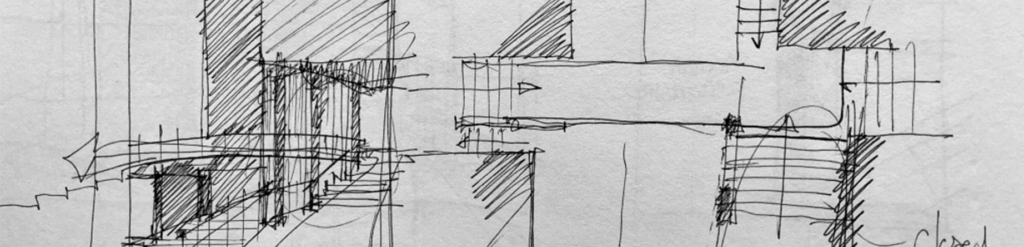

For students, I wanted them to become cognizant of what was routine and had become commonplace as they moved through the city. New spatial configurations could be understood through rough and rapid sketches; lines creating perspectives became alive through various intensities of shading while anticipating with arrows and other techniques the light sources that so often are part of the constant contrast one experiences when walking in Venice. In my sketches (all images in this blog) I delighted in giving spatiality by including , and overlapping in the drawing, plans and sections of the stairs which often anticipate a bridge (Venice has over 400 bridges). The steps would extend into the street creating a Piranesian world that I could simultaneously experience and translate in my sketchbook (Image 6, below).

Conclusion

Experiencing space may come to some naturally with confidence, while for others, it remains something that is unnoticed. I hope that students – or anyone for that matter – will be encouraged to pay attention to their journey. Whether sketching or simply walking back and forth during the work day, the spaces between the buildings are what create our urban environments and deserve our attention. When traveling, all of the senses are celebrated and memories are created. Each sketch becomes a montage of frames, a possible Eisenstein script for a movie about a city, the student’s city of memory.

Sketching as reflection-in-action

Cinematographic traveling in architecture

The importance of sketching for architects, Part 1

Some thoughts on sketching by hand

Sketching on a field trip, Part 1

Sketching on a field trip, Part 2

Issues about sketching, Part 1

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 2

Sketching -an iterative process, Part 1

Architectural Education: What issues does one encounter when sketching?

Why Model Sketching? Part 5

Why Model Sketching? Part 4

Why Model Sketching? Part 3

Why Model Sketching? Part 2

Why Model Sketching? Part 1

Inspiring content, I find myself trying to take steps back to understand the essence of what a pencil on paper can allow me to express and think about architecture.