National Museum in Singapore, Part 1. Over the past decades, art museums have outgrown their spatial footprint; be it an 18th or 19th century heritage facility or a contemporary addition. I mention these centuries, as during that period major modern museums were founded.

For example, the British Museum in London (1753), the Louvre in Paris (1793), the Prado in Madrid (1819), the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City (1870), and the Uffizi in Florence (1889) were all established and became part of the great museum-building type whose institutional identities have subsequently reverberated throughout the art world.

Identities of museums

The identities of these museums developed through both the Beaux-Arts architectural style of their buildings and the distinctiveness of their collections. Ironically, today I find fewer and fewer museums stand out as exceptional in terms of the singularity of their collections. Two that do are the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, and the Latvian National Museum of Art in Riga; each distinctive for a different reason.

One of the causes of the recent growth spurt in museums is the current need to diversify existing collections, be it through well-funded endowments, or donations from private and public sources. To respond to this challenge, robust acquisition efforts have expanded the definition of what constitutes art. To demarcate themselves in their pursuit of inclusiveness (yes, this thought might seem an oxymoron), museums also seek to increase flexibility for their permanent and rotating exhibitions. This perhaps is the result of museums need to accommodate a growing cultural phenomenon of exceptional attention-grabbing traveling blockbuster exhibitions—although this phenomenon is credited to have been invented in the 1870s by the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

Museum growth patterns

Thus, over several decades, we have seen the broadening of the educational and public role of the museum in addition to their need to present more artwork to the public. This has often created a deaccessioning moment where core collections are forfeited to fund newer buildings (e.g., Thomas Krens during his tenure at the Guggenheim Museum). Other institutions have created satellite annexes: Guggenheim Bilbao by Frank O. Gehry; Louvre Abu Dhabi by Jean Nouvel, and even the airport museum in Istanbul (the largest of its kind at c. 11.000 square feet); and the 24 hour Rijksmuseum at Schiphol’s airport in Amsterdam. These growth patterns demonstrate, once again, the result of the urgent need for museums to expand beyond their current facilities, while holding dear to their past identity, all the while defining a future curatorial mission that balances prewar, postwar, and contemporary collections.

As a side note regarding the two airport museum annexes, I am reminded of the statement by French anthropologist Marc Augé, that the places of the 21st century will be the non-places such as airports, bus terminals, hotels that we encounter during our travels (Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity (1995)). These transitional non-places have now, in the airports of Istanbul, Amsterdam, and Singapore, allowed travelers to explore art before or after their flight; at the airport in Singapore there is no museum per se, but there is a unique butterfly garden in a portion of the airport designed as a tropical butterfly habitat.

Addition to two famous museums

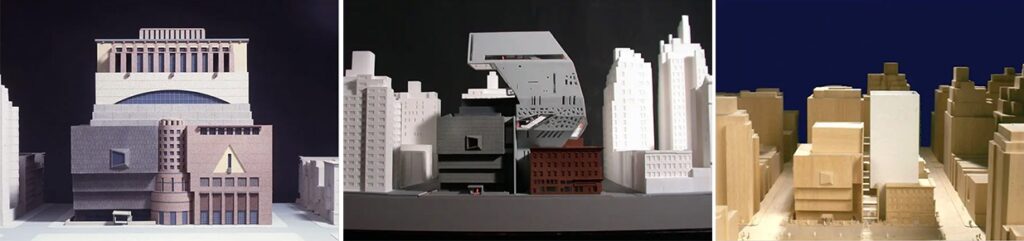

This current need for increased space follows a similar burst of museum growth in the late 20th century, which was often seen as controversial, and sometimes was halted due to hostile neighborhood activism, preservation advocates, landmark constraints, and occasionally a capricious board of trustees. This was true for the projects by Michael Graves, Rem Koolhaas, and Renzo Piano for the extension of the Whitney Museum in New York City originally designed in 1966 by Bauhaus architect Marcel Breuer (Image 1, below). The same was true for the abandonment of Romaldo Giurgola’s 1990 addition to the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas: a museum initially designed by American architect Louis I. Kahn, that ended up years later with a successful addition by Renzo Piano.

These proposed additions to the Whitney and the Kimball were necessary and also visionary, but they would have, in my opinion, distorted the distinctive appearance and integrity of the design as envisioned by the original architects. Of course, my comment opens up Pandora’s box as to the question of which value system is appropriate when adding to iconic edifices with equally atypical and exceptional strategies. Perhaps a polemical topic to be covered in a future blog!

Whether for prestige, cultural distinction, or social change, the need to update many museum facilities has been equally encouraged by an increase in the number of museum goers, whose appetite for art is more than ever a pastime, as spending hours wandering through galleries has grown exponentially. This is particularly true post Covid-19, now that social distancing is over and crowds have returned—and even expanded; although with some additional health and safety guidelines.

The museum now rewards the public by providing visitors with connections through storytelling about the nature of art, a connection that emphasizes a window to the uniqueness of culture and the global expansiveness of cultures. This educational approach is perhaps why many museums have also developed new curatorial strategies that compare and contrast between paintings of various periods (e.g., North Carolina Museum of Art). This is a change from an earlier era when museums focused on telling people what art to appreciate.

Three suggested strategies

In their need for growth, I see that museum boards have three basic options to expand their facilities:

By either demolishing the existing edifice(s) and building anew; a position which I believe has become ecologically and financially unsustainable, and is particularly contentious given current preservation ethics (e.g., the new LACMA by Peter Zumthor).

By adding or enlarging the current facilities, thus joining the new with the old (e.g., Prado by Raphael Moneo).

Or by erecting a stand-alone structure next to the building; or locating the addition at a distance from the current museum on a more convenient site (e.g., Getty Museum, Los Angeles by Richard Meier, or Kunsthaus in Zurich by David Chipperfield).

More about Chipperfield: click on image below

An alternative approach: the museography of Carlo Scarpa

Of the many options presented to museum boards, I favor a richer and more complex strategy that finds its antecedents in the seminal work of Italian architect Carlo Scarpa. His philosophy when working with existing structures was to enter into a dialogue between the new and the old, so that both entities could work in tandem and complement each other. This was done in ways that recognized the diverse ideals and tastes of the architects’ time in relation to spatial configurations, structural principles, and material choices.

Scarpa in particular had a vision for contemporary museography that favored displaying works of art that were integral to the proposed spatial order. Countless museum interventions by Scarpa (Castelvecchio, Gipsoteca Antonio Canova, Fondazione Querini Stampalia, Museo Correr, and the Galleria dell ’Accademia) were based on an emerging museum type—that he created—that blends the historical context with the new; recognizing in an humbler manner the signature of each architect, without mimicking the past either in style or language.

In today’s culture of the star-architects (contrary to the master-architect), isolated self-congratulatory interventions are de rigeur, and Carlo Scarpa’s approach has not been a primary leitmotif in a way of practicing architecture in a dialogue with the original author.

More about Scarpa: click on image below

Conclusion

It will be interesting to see what the future holds. Certainly some have adopted this humbler approach to build a strong building through an addition to an existing museum. Specifically, I’m thinking of the National Museum in Singapore, a theme I will develop in Addition to the National Museum in Singapore. Part 2.

Additional blogs pertaining the city of Singapore

National Museum in Singapore, Part 2

Hotel Park Royal Collection Pickering, Singapore

People’s Park Complex in Singapore, Part 1

People’s Park Complex in Singapore, Part 2

People’s Park Complex in Singapore, Part 3

Additional blogs pertaining to issues of preservation

Addition to the National Museum in Singapore. Part 2

A question of Preservation

Hong Kong: the history of Central Market

Ballenberg: a vernacular architecture museum

Speicherstadt in Hamburg. Part 1

Speicherstadt in Hamburg. Part 2

Carlo Scarpa Gavina Showroom in Bologna, Italy. Part 1

Carlo Scarpa Gavina Showroom in Bologna, Italy. Part 2

Carlo Scarpa Gipsoteca in Possagno, Italy

Carlo Scarpa and detailing

Lesson from vernacular architecture -inventing versus re-invention

Street pavement: Wittenberg, Germany

Church façade in Ticino, Switzerland: Part 1

Church façade in Ticino, Switzerland: Part 2